Saifullah Paracha, Guantánamo’s Oldest Prisoner, Finally Freed – OpEd

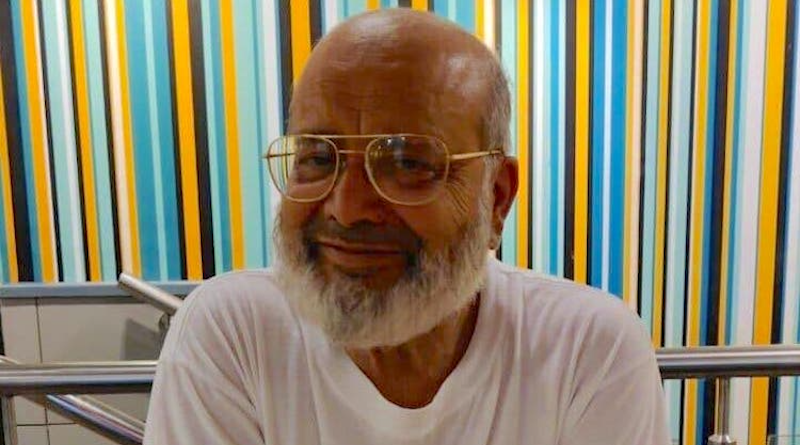

It took 19 years and three months, but finally Saifullah Paracha, 75, Guantánamo’s oldest prisoner, has been freed from the prison and repatriated to Pakistan, where he has been reunited with his family. The photo at the top of this article was taken as he celebrated his freedom in Karachi, with a cup of tea in a branch of McDonald’s. It was posted on Twitter on October 29 by one of his lawyers, Clive Stafford Smith, the founder of Reprieve, who called it a “belatedly happy day,” noting that “he should never have been kidnapped & locked up 18 [actually 19] yrs ago.”

In a follow-up tweet on October 30, Stafford Smith added that he had “just had the nicest morning chat” with Saifullah, also explaining that, until the very end, the hysterical over-reaction that has typified the US’s treatment of the 779 men it largely rounded up indiscriminately, sent to Guantánamo, and then fabricated reasons for holding them indefinitely without charge or trial, was still in place. “It took 40 US personnel to take one 75 yo home from Guantánamo Bay”, Stafford Smith wrote.

The over-reaction was grotesque on two fronts: firstly, because Saifullah was regarded as a model prisoner at Guantánamo, who, as the US authorities explained in 2016, “has been very compliant with the detention staff and espouses moderate views and acceptance of Western norms,” and “has focused on improving cell block conditions and helping some detainees improve their English-language and business skills”; and, secondly, because a robust government review process — the Periodic Review Boards, involving “one senior official from the Departments of Defense, Homeland Security, Justice, and State; the Joint Staff, and the Office of the Director of National Intelligence” — had unanimously concluded, in May 2021, that “continued law of war detention [was] no longer necessary to protect against a continuing significant threat to the security of the United States.”

That careful wording is designed to prevent the US government from being accused of having made mistakes in the post-9/11 global dragnet that filled Guantánamo and the CIA’s “black sites,” but in the case of Saifullah, who was kidnapped in Thailand in July 2003, where he had been lured by the FBI to attend a non-existent business meeting, based on suspicions that he was involved with Al-Qaeda, there were profound doubts about these claims from the very beginning.

Saifullah’s story — and that of his son Uzair

A successful businessman, Saifullah had lived and worked in the US from 1970 to 1986, where he had married, and had four children. In 2006, I researched his story — and that of over half the men held at Guantánamo — for my book The Guantánamo Files, based on an analysis of 8,000 pages of documents relating to Guantánamo, which the US government had been compelled to release through a Freedom of Information lawsuit. I noted that, although Saifullah “acknowledged that he had met Osama bin Laden twice, at meetings of businessmen and religious leaders in 1999 and 2000,” he “denied the allegations against him, which included making investments for al-Qaeda members, translating statements for bin Laden, joining in a plot to smuggle explosives into the US and recommending that nuclear weapons be used against US soldiers.”

I added, “These were indeed wild accusations for anyone familiar with his story. Deeply impressed by all things American, he had lived in the US in the [1970s and] 1980s, running several small businesses, and after returning to Pakistan had made a fortune running a clothes exporting business in partnership with a New York-based Jewish entrepreneur (an unthinkable association for someone who was actually involved with al-Qaeda).”

I also examined how his case was inextricably linked with that of his eldest son Uzair, who, in February 2003, had traveled to New York, “where he was marketing apartments to the Pakistani community.” On March 31, 2003, Uzair was arrested by FBI agents, and accused of working with Ammar al-Baluchi and Majid Khan, “high-value detainees” who were already in US custody, “to provide false documents to help Khan enter the US to carry out attacks on petrol stations,” as I described it in The Guantánamo Files. In November 2005, Uzair was convicted in a US court and given a 30-year sentence in July 2006, even though, as I added, “he said that he was coerced into making a false confession, and both Khan and al-Baluchi made statements that neither Uzair nor his father had ever knowingly aided al-Qaeda.”

This outline of the Parachas’ story actually seems to be quite close to the truth, although it took many, many years for it to have any impact on either Saifullah or Uzair’s cases. In July 2007, in one of my first in-depth articles after completing The Guantánamo Files, I revisited some of my doubts in an article entitled, “Guantánamo’s tangled web: Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, Majid Khan, dubious US convictions, and a dying man,” bringing the alleged 9/11 mastermind into the picture, who had presented himself to Saifullah as a businessman, as had al-Baluchi and Khan.

By that point, I knew more about how Uzair, apparently on the advice of his father, “had foolishly attempted to secure an immigration document for Khan, as a favor for a fellow Pakistani, and that as a result he ‘posed as Khan during telephone calls with the Immigration and Naturalization Service,’ and also called Khan’s bank, attempted to gather information about his immigration paperwork via the internet, and agreed to use Khan’s credit card to make it appear that he was in the United States, when he was actually in Pakistan.” However, I noted that Uzair “denied stating, as the DoJ attempted to assert, that he ‘knew from his father’ that Khan and al-Baluchi ‘were al-Qaeda,’” and that he also denied knowing that up to $200,000, loaned to his father’s company, ”was al-Qaeda money, and that al-Qaeda wanted to keep the money liquid so they could have it back at a moment’s notice.”

I also discovered more about his alleged false confession, as one of his lawyers, Edward Wilford, “told the court that the government’s claims stemmed from a false confession Uzair gave after he was ‘subjected to 72 hours of interrogation without being told that he could consult a lawyer or speak with his parents.’”

I also learned how ill Saifullah was, having suffered two heart attacks in Bagram, the main US prison in Afghanistan, where he was taken after his kidnapping in July 2003, and another heart attack in Guantánamo, where he was transferred in September 2004. Another of his lawyers, Gaillard T. Hunt, suggested that his medical treatment at Guantánamo was “at best incompetent and at worst negligent,” explaining that he “couldn’t submit to a cardiac catheterization at Guantánamo because the rules require all prisoners in the hospital to be shackled to the four corners of the bed. The cardiologist said this was dangerous for a heart patient, but the prison administration would not compromise.”

From prosecution candidate to “forever prisoner”

None of the above, however, swayed the US authorities from their determination that Saifullah was “a significant member of the international al-Qaida support network who provided assistance to al-Qaida operations and personnel.” That claim was contained in his Detainee Assessment Brief, a classified document, dated December 1, 2008, which was only publicly revealed in April 2011, when, after being leaked with files relating to almost all the prisoners by Chelsea Manning, it was published by WikiLeaks, in a project on which I worked as a media partner. Helpfully, however, the file also revealed that he was “on a list of high-risk detainees from a health perspective,” noting his diabetes and other ailments as well as his history of “coronary artery disease” — although his heart attacks weren’t specifically mentioned.

The exaggerated analysis of Saifullah’s role, as revealed in the file, presumably formed the basis of the recommendation in January 2010 by President Obama’s first review process, the Guantánamo Review Task Force, that he should be put forward for prosecution along with 35 other men out of the 240 men held at the start of Obama’s presidency. That, however, never happened, and by 2013 he had been shifted instead into a category of prisoners — correctly identified in the mainstream media as “forever prisoners” — who wouldn’t be charged, but who hadn’t been recommended for release either, and who would be held indefinitely without charge or trial unless a new review system, a parole-type process known as the Periodic Review Boards, established that it was safe to recommend them for release.

Saifullah’s PRB took place in March 2016, but his ongoing imprisonment without charge or trial was approved a month later, because of his “refusal to take responsibility for his involvement with al-Qaeda, his inability and refusal to distinguish between legitimate and nefarious business contacts, his indifference toward the impact of his prior actions, and his lack of a plan to prevent exposure to avenues of reengagement,” as the board members explained.

As another of his lawyers, David Remes, had explained at his hearing, Saifullah “cannot show ‘remorse’ for things he maintains he never did,” but, for anyone like Saifullah, who maintained their innocence at a PRB hearing, it was impossible to secure a recommendation for release. The PRBs were not concerned with verifying innocence or guilt, but, instead, as a parole-type process, guilt was assumed (as was, in fact, the general rule at Guantánamo), requiring contrition and a credible plan for a peaceful life if they were to be freed.

With Saifullah’s refusal to show contrition, it didn’t matter that, as David Remes had also explained to the board members at his hearing, “Mr. Paracha has been an enormously positive influence on other detainees. Other detainees call him ‘Uncle,’ a term of great respect for male elders, and seek out his advice. Wise and understanding, he discourages conflict and calms detainees when they are agitated. He promotes harmony among religions. He taught classes in business administration and English. Once, when other facilities were unavailable, he set up class in a cell.”

As Remes also explained, “Mr. Paracha also counseled cooperation with the government in the judicial and administrative review process. When the Supreme Court in 2004 gave detainees the green light to pursue habeas corpus cases, Mr. Paracha urged his fellows to accept help from the American lawyers. When the Periodic Review Board opened for business in July 2013, he urged them to participate in the process.”

Disturbingly, the board members also ignored the passages about Saifullah and Uzair in the unclassified summary of the Senate Intelligence Committee’s report into the CIA’s torture program, which was released in December 2014. In it, the Committee refuted claims made by the CIA that it was only through the use of torture that Uzair and Saifullah had been identified, noting that the Parachas had been on the Pakistani intelligence services’ radar long before the torture took place, but also, more importantly, expressed skepticism about the claim that they were knowingly involved in an attempt to smuggle explosives into the US, a claim attributed to Khalid Sheikh Mohammed.

As “a senior CIA counterterrorism official” commented, “again, another ksm op worthy of lamentable knuckleheads … why ‘smuggle’ in explosives when you can get them here [in the US]? neither fertiliser for bombs or regular explosives are that hard to come by. ramzi yousef [a nephew of KSM’s who tried to blow up the Twin Towers in 1993] came to conus [the continental United States] with a suitcase and [a] hundred bucks and got everything he needed here. this [KSM’s “confession”] may be true, but just seems damn odd to me.”

In 2017, Saifullah’s imprisonment was once more upheld by a PRB, apparently consigning him to endless imprisonment without charge or trial, even though, in October 2018, Mansoor Adayfi, a former prisoner who had been released in Serbia in 2016, wrote an extraordinarily glowing testimonial about him, entitled, “Saifullah Paracha: The Kind Father, Brother, and Friend for All at Guantánamo,” which was published exclusively on the Close Guantánamo website.

In it, Mansoor wrote at length about how Chacha (“uncle” in Urdu) inspired the younger prisoners, through teaching them English, preparing “a business plan — for a ‘milk and honey’ farm business in Yemen,” which some of the Yemenis used in their PRBs, through his cooking, and through significant emotional support. “He treated me as his own son, and I love him like a father,” Mansoor wrote.

The turning point: Uzair’s conviction is quashed

When the turning point came in Saifullah’s fortunes, it was not because of anything that happened at Guantánamo, where, as I hope to have established, guilt is presumed, and strenuous efforts are persistently made to refute any other version of events; instead, it came on the US mainland, where the law — though often abused — can still involve a robust analysis of actual facts by a judge (a luxury that only ever applied at Guantánamo between 2008 and 2010, from when the Supreme Court granted the prisoners constitutionally guaranteed habeas corpus rights to when politically motivated appeal court judges conspired to make those rights meaningless).

In July 2018, in New York, Judge Sidney H. Stein, who who had been the judge in Uzair’s original trial, and had handed down his 30-year sentence, threw out his sentence, and ordered a retrial, after concluding that allowing the existing conviction to stand would be a “manifest injustice,” as I explained in an article in March 2020.

Unlike at Guantánamo, where inconvenient truths can, apparently, be endlessly ignored, especially via the PRBs, which are not even concerned with the truth, Judge Stein examined the evidence, and concluded that anything incriminating uttered by Uzair had come about because of “a combination of fear, intimidation and exhaustion” at his initial interrogation. Judge Stein also drew on reports establishing that Majid Khan, Ammar al-Baluchi and KSM had all made statements that “directly contradict[ed] the government’s case” that Uzair Paracha “knowingly aided Al-Qaeda,” seizing in particular on a statement by Khan, who “told the authorities that he had never disclosed his Qaeda ties to Mr. Paracha, whom he described as innocent.”

It took another 20 months, but, in March 2020, the US government abandoned its efforts to pursue a retrial, and Uzair — stripped of his status as a permanent US resident — was flown home, a free man. For Saifullah, however, the limbo of Guantánamo continued. As I explained at the time, “while Uzair Paracha is now a free man, there is no guarantee that his father will also be released, because, although the profound doubts about the reliability of those who, under duress, accused him of being knowingly involved with Al-Qaeda are just as applicable to the case against Saifullah Paracha, the horrible truth about Guantánamo is that suspicions are regarded as far more compelling than evidence.”

In fact, it took another 14 months for a PRB to finally approve Saifullah for release, on May 13, 2021, and nearly another year and a half for him finally be sent home, even though, last May, Shelby Sullivan-Bennis, another of his lawyers, had stated that she thought he would be “returned home in the next several months,” because “the Pakistanis want him back, and our understanding is that there are no impediments to his return.”

There may not have been actual impediments, but at Guantánamo actual impediments aren’t required when the prevailing modus operandi, when it comes to releasing men approved for release, is a state of colossal inertia.

I am so thrilled for Saifullah, but none of us must forget that 20 other men who have been approved for release — three since 2010, one since 2019, and 16 since President Biden took office (some, like Saifullah, told that the US no longer wanted to hold them last May) — are still held, because no legal mechanism exists to compel the US government to free men whose release has been ordered though administrative processes like the PRBs and its predecessor, the Guantánamo Review Task Force.

Also awaiting release is Majid Khan, whose truth-telling helped secure Uzair’s freedom — and by extension Saifullah’s. Khan expressed complete remorse for his role as an Al-Qaeda facilitator, became a cooperating witness, and eventually received a sentence, after a plea deal in 2012, that ended on March 1 this year. Six months later, however, he too is still in limbo, as no country has yet been found that will offer him a new home, and, as with the 20 men mentioned above, there is no sign of any of the required urgency to secure his release on the part of the US government.

Shamefully, this inertia is also maintained because Democrats fear a Republican backlash in Congress, and also because the mainstream media — and, sadly, the majority of the American people — just don’t care.

As we celebrate Saifullah’s release, it is time for this inertia and indifference to be overcome, and for all the other men approved for release to also be freed.