Democratic Primaries: The Establishment Fights Back – Analysis

By Observer Research Foundation

By Seema Sirohi

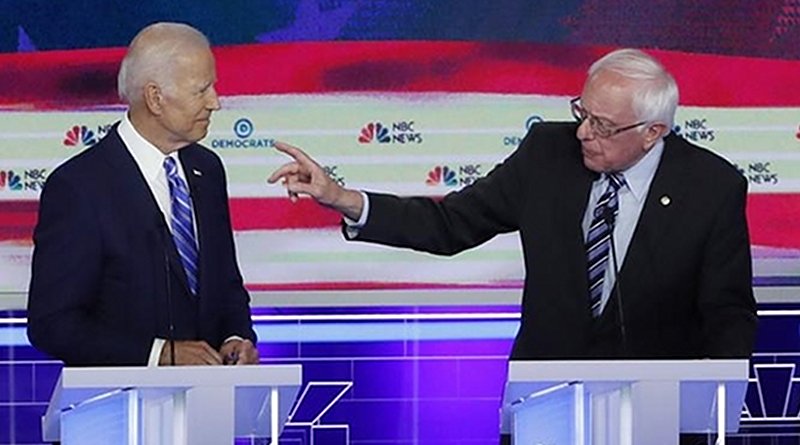

It’s now realistically a two-man race for the Democratic Party nomination after Joe Biden’s exceptionally strong performance against Bernie Sanders in the Super Tuesday primaries. With Biden’s resurgence, the Democratic Party establishment has successfully forced the issue and the choice that goes with it – revolution or status quo?

Rep. Tulsi Gabbard remains in the race, but has only won two pledged delegates.

It seems a lot more Democrats, especially moderates and conservatives, want the status quo that Biden represents. They are happy with incremental gains, student loan debt, and a broken health care system. They don’t want to rock the boat as much as Sanders would have them do.

After three years of turbulence under Donald Trump, more disruption or a revolution is deemed undesirable by the party stalwarts and older voters. Younger voters who are behind Sanders in overwhelming numbers are not as threatened by a “revolution” but they form a smaller demographic.

Interestingly, it was African Americans who have revived Biden’s somnolent and badly organised campaign by giving him a much-needed win in South Carolina last Saturday. Super Tuesday followed two days later and he won 10 of the 14 states voting, including some with a large African American population.

The race for the nomination was transformed overnight and the field placements changed dramatically. Sanders and his energetic band of young supporters have been pushed back, at least for now, and Elizabeth Warren — the other progressive running for the nomination — is expected to drop out as three others have and leave the field to the two frontrunners.

Biden currently leads with 433 delegates and Sanders is in second place with 388. At least 1,991 delegates are needed to win the nomination. To be sure, 60% of the delegates are still up for grabs in various state primaries before the party convention in June will crown the nominee who will go against Trump. A lot could happen between now and then.

But what’s clear is that the Democratic Party is having its own “Never Trump” moment. “Never Bernie” became a real thing after he won two of the three primaries in Iowa, New Hampshire and Nevada that began the process. The establishment became nervous, media pundits turned openly against Sanders and questions were raised whether he was the right candidate to defeat Trump.

It makes for a political thriller how different members of the establishment — from former presidents, almost presidents, donors, old-time strategists to the Democrats currently serving in the House and Senate — coalesced and formed an invisible wall. The argument: Sanders’ momentum had to be thwarted because his nomination could cost Democrats the majority in the House and dash whatever faint hope the party had of taking the Senate.

The Democrats won the House of Representatives in 2018 on an anti-Trump wave but on the shoulders of older, college-educated, socially conservative supporters who don’t live on either coast but in the suburbs of the middle country and Trump country. They could flip back to Republicans at any talk of a revolution.

In other words, Sanders was deemed too risky and his agenda too left-wing on key issues, immigration being a huge one. Polls show Democratic voters are opposed to free health care for illegal immigrants, eliminating ICE or US Immigration and Customs Enforcement and “decriminalizing” the border – all of which Sanders supports.

A day before Super Tuesday when a big haul of delegates from 14 states, including California and Texas was at stake, two rival candidates – Pete Buttigieg and Amy Klobuchar – dropped out of the nomination race and endorsed Biden. The timing was immensely helpful because it narrowed the field to essentially three contenders – Sanders, Warren and Biden.

Michael Bloomberg, whose vanity campaign got him nothing for his $500 million in television advertising, dropped out a day after Super Tuesday and pledged his support and campaign infrastructure to Biden. What it all means is that Democrats think Biden is the best candidate to drive Trump out of the White House – the most important motivation this election cycle. Almost nothing else matters in 2020.

Biden’s record on policy issues – he has advocated cuts in Social Security and Medicare both – is not an overwhelming concern. He voted for the Iraq War and as vice president advised Barack Obama to get out of Afghanistan against the counsel of others, including the Pentagon generals.

What Biden has going for him this time around is the strong support he enjoys among African Americans and moderate Democrats, two constituencies without whom a Democrat cannot win the presidency. In addition, he will have the support of the party structure, Congressional Democrats and those who don’t travel as far as Sanders on the ideological spectrum.

Sanders, on the other hand, has struggled to connect with African Americans even though he talks about issues that directly affect them and their pocket books. His campaign also has some difficulty wooing women because of the perception that his supporters are bullies and sexist. From a foreign policy point of view, Biden would be a more predictable candidate and more likely to support maintaining a favourable balance of power in Asia. That means Trump’s Indo-Pacific policy would essentially continue even if it changes names and dials down on rhetoric against China.

Sanders’ foreign policy would be based more on “values,” which means a bigger focus on human rights. India has already faced a battery of comments from the candidate, most recently on the violence in Delhi. Sanders and his advisers have also advocated cuts in the defence budget and reducing the number of US troops stationed in various countries which indicates a general preference for retrenchment – a trend in both Democrat and Republican thinking. But what a progressive US foreign policy ultimately might look like is not yet clear.

A return to a more traditional foreign policy paradigm will certainly placate US allies jolted by three years of Trump. What it might mean for countries such as India that saw opportunities in Trump’s disruptive ways is another matter.