Transition In Algeria: More Than What Meets The Eye – OpEd

With frail President Abdelaziz Bouteflika stepping down and apologizing to the nation, Algeria is entering a new phase in which many observers see a revival of the Arab Spring. However, Algerians are too sophisticated to experience an Arab Spring as others seem to want. That type of event is highly unlikely given the country’s history.

Unlike the Arab Spring, this transfer of power is a controlled transition to a hopefully better society. Any transfer of power is wrought with intense infighting over power and assets, but once that is worked out — and in Algeria’s case it will be peaceful— a process will begin to elect a new leader given the country’s unique sociopolitical landscape.

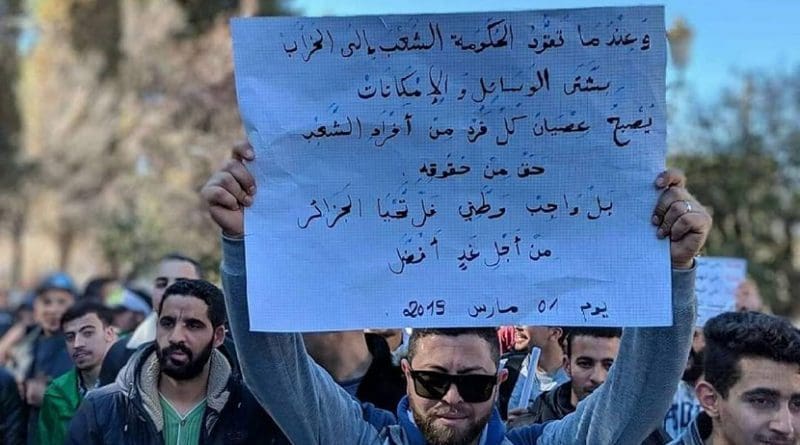

This landscape has been shaped by history. Make no mistake, the events of the past weeks have been extraordinary and necessary. What is remarkable is that so far this transfer has been vocal and peaceful. Surely this is better than chaos, which no interested party, including Russia, wants.

At a basic level, Algeria’s street demonstrations need to be viewed in the context of the country’s recent history. Any comparisons with the 1988 Black October riots are tenuous. At the time Algeria was a disjointed civil society with a polarized elite that was able to play one political faction off against another. In addition, there were lingering memories of the Algerian war of independence. Studies that focus on post-war environments look at the role historical memory plays in shaping future relations. That factor is a special case in Algeria.

Algerians are wary of the Arab Spring and its unknown ramifications, especially with the still vivid legacy of civil strife and bloodshed of the 1990s. The country’s neighbors are watching its transition carefully given the events in Libya and in the wake of the Arab Summit in Tunisia.

To be clear, Algerians fear and loathe the current government, but Bouteflika’s stepping down in such an undignified matter means a feared Libyan or Syrian-style implosion can be avoided.

Algeria’s Prime Minister Ahmed Ouyahia warned that rioting or civil disturbances might result in a “Syrian-style environment” because of the country’s religious and political landscape. Ahmed Gaid Saleh, the army chief of staff, said that “internal and foreign” elements will seek to infiltrate demonstrations and destabilize the country. This is not propaganda. Al-Qaeda or Daesh-related groups and gangs will be drawn to protests in the country, threatening safety and security.

From an outside perspective, Algeria’s transition is being watched carefully. As the transition continues, Algiers must remain a key ally with the West in the fight against global terrorism, organized crime and illegal immigration to Europe. The situation in northern Mali has made cooperation between France and the Algerian security services even more critical. Such cooperation cannot be threatened given current events in countries ranging from Morocco to Egypt.

Russia is also taking a strong interest in what happens next in Algeria. History matters here, too. Soviet policy toward Algeria was viewed through the lens of Cold War rivalry over former French colonies. Across northern Africa, the Soviet Union used support for revolutionary and popular movements, arms sales and sports as its main tools of trade. Soviet support for the western Sahara led to complications in its bilateral relations with Morocco, with which the USSR had extensive trade relations. Bouteflika’s rise occurred during the Soviet Union’s collapse and thus a break between the two countries occurred. These relations set the stage for Russia’s return to Algeria in the 2000s.

In March 2006, Russian leader Vladimir Putin visited Algeria, two years before his double visit to the Arabian Gulf. At the time, Russia signed major arms agreements with Algeria as well as a settlement of Algeria’s debt to the Soviet Union, leading to a closer relationship between the two countries. Debt relief was also used in Syria to ensure future deals and concessions.

Algerian state oil company Sonatrach’s agreement with Russia’s Lukoil sent shock waves through Europe over the potential for both countries to act together to squeeze European energy supplies. Russia’s interest is in maintaining current contracts. Watching Sonatrach is important because of the state company’s concessions in Libya, Mauritania, Peru, Yemen and Venezuela. A recent deal with India is part of a wider geopolitical picture involving Arabian Peninsula downstream operations.

Russia’s activity shows that Moscow’s interest in North Africa is based on older Soviet ties and objectives with a modern twist. Russia sees the current transition as one that could challenge but also benefit the Kremlin. Algeria’s ties to key Arab countries will help Algerian elites work through what happens next to the country.

Clearly, the past few weeks show that the moniker of Arab Spring is too simple for the Algerian transition. Sophisticated protests and transitional leadership are critical for the country and its international partners at a time of heightened uncertainty across northern Africa. Those who shout Arab Spring are actually bringing trouble.