Shaker Aamer’s Latest Words From Guantánamo: Fearful Won’t See His Family Again – OpEd

Yesterday, just ten days after the announcement that Shaker Aamer is finally to be freed from Guantánamo and returned to his family, was quite a disturbing day for those of us who care about Shaker and his health, as the Mail on Sunday ran a seven-page feature on Shaker that centered on his lawyer Clive Stafford Smith’s report of his latest words from Guantánamo, via a recent phone call.

Shaker stated, as the Mail on Sunday put it, that “he is on a hunger strike in protest at an assault by guards, who, he says, forced him to give blood samples,” and that he is “still being subjected to brutal physical abuse” by the authorities, and he also expressed his fears that he will not make it out of Guantánamo alive. As he said in his own words: “I know there are people who do not want me ever to see the sun again. It means nothing that they have signed papers, as anything can happen before I get out. So if I die, it will be the full responsibility of the Americans.”

This is rather bleak, and it made those of us who worry about Shaker’s health very unsettled. In my conversations with people yesterday, we also reflected on how the news must have been very disturbing for Shaker’s family. However, it is not all darkness. In another key passage, not picked up by the headline writers, Shaker said, powerfully, in words that illuminate his passion for justice and the tenacity that so many of us have admired over the years, “I do not want to be a hero. I am less than a lot of people who suffered in this place. But all this time I stood for certain principles: for human rights, freedom of speech, and democracy. I cannot give up.”

Also included in the newspaper’s coverage were excerpts from Shaker’s 24,000-word statement about his long ordeal, which he provided to Metropolitan Police detectives who visited him at Guantánamo two years ago in response to a court case in the UK in 2009 that involved allegations that he was abused by US personnel in Bagram, Afghanistan, while UK agents were in the room. I’ll cross-post a large excerpt published by the Mail on Sunday in a follow-up article, but a key section, singled out for particular attention by the newspaper, concerned Shaker’s role as a witness to the “extraordinary rendition” of Ibn al-Shaykh al-Libi, the head of an independent training camp, not aligned with al-Qaeda, who, after being placed in a coffin, was flown by the CIA to Egypt, where, under torture, he made a false claim about a connection between Saddam Hussein and al-Qaeda, regarding chemical weapons, that was later used to justify the illegal invasion of Iraq in 2003.

I have written extensively about al-Libi over the years — focusing on the extraction and use of the “confession” as a key piece of evidence in the case for the prosecution of Dick Cheney for treason, as discussed in my April 2009 article, Even In Cheney’s Bleak World, The Al-Qaeda-Iraq Torture Story Is A New Low, although, as the Mail on Sunday notes, al-Libi’s treatment and his false confession could also “have grave consequences for Tony Blair and the troubled Chilcot Inquiry into the war.”

In May 2009, I also broke the story (in English) of al-Libi’s profoundly suspicious death (also see here), allegedly by committing suicide, after he had been shunted around various CIA ‘black sites,” including the one at Guantánamo, eventually being returned to Col. Gaddafi who imprisoned him in the notorious Abu Salim prison in Tripoli. Please also see my world exclusive article about al-Libi from June 2009, New Revelations About The Torture Of Ibn al-Shaykh al-Libi.

The Conservative MP David Davis, the co-chair of the Shaker Aamer Parliamentary Group (founded last November by John McDonnell, the other co-chair, and now, of course, Labour’s shadow chancellor) responded to the news by stating that the revelations “‘massively strengthened’ the case for an independent inquiry into Britain’s alleged involvement in the systematic torture of terror suspects,” as the Mail on Sunday described it. Davis said, “The time has come for the Government to face up to Britain’s role in torture and rendition. Only by dealing with it can we restore our nation’s honour and integrity.”

Clive Stafford Smith also made a statement. “It may be that no one has suffered more at Guantánamo than Shaker Aamer, because he stood up for his rights and the rights of others — and for this he has constantly been punished,” he said, adding, “Mr. Cameron’s government likes to harp on about the need for people to take responsibility for their actions. Surely Britain must now accept its responsibility for this.”

Below are Shaker’s words, as delivered to Clive, and at the end of this article are excerpts — and further analysis — of Shaker’s account of the extraordinary rendition of Ibn al-Shaykh al-Libi, and also an account by another of Shaker’s lawyers, Ramzi Kassem, a professor at the City University of New York School of Law, who, with his students, represents Shaker and other Guantánamo prisoners. Ramzi wrote of his visit to Guantánamo last week when he was able to break the news to Shaker of his impending release — news that didn’t register at first, so small had Shaker’s world become, and so stunted his hope. One he realized, however, Ramzi describes how “an impossibly large smile lit up his face and his gaze suddenly grew distant. A door had finally swung open, and he was looking ahead at everything that lay beyond.”

Shaker Aamer speaks from Guantánamo, October 1, 2015

I saw my kids in a dream three days ago. Not as they are today, but as they were when I last saw them, almost 14 years ago. The little children I knew and loved so much no longer exist: they have grown up. I have at least been able to see them: on a handful of rare occasions the Guantánamo authorities have let me talk to my family on a video call via Skype. But the images I have from those conversations are not what I saw in my dream.

The dream brought home to me the scale of the shock I’m about to face. Everything I once knew has changed, almost beyond recognition.

The kids need to see me as a strong father, but that is just not going to happen from the first second I get back. I don’t know how long it is going to be before I can begin to deal with the world out there, beyond the walls of Guantánamo. It may be a day. It may be a week. It may be longer. I just don’t know, just as I don’t know the date of my release. This ordeal won’t be over until it’s over.

I was first cleared for release eight years ago, yet here I still am. I still don’t believe that at last, I’m on my way home. That’s why my message for my wife and kids is: stay strong. Regardless whether it is next month, next year, or even in heaven that I am finally released to be with you, stay strong, because you need to be strong, not because you hear some news that I may be coming home, that may not even be true.

In here, I am laughing, I am joking, but I am also screaming. The wound I carry lies deep inside, and I know this wound will start gushing as soon as I leave this place. Don’t be fooled by my exterior. The reality is that I am a very sensitive person. The moment I touch freedom, 239 [Shaker’s Guantánamo prison number] is going to come back with a lot of issues, and I will need to solve them one by one.

To begin with, I need to re-acclimatise by spending time with my wife. I need to reclaim my personality: to put a name to my prison number.

I have so many people to thank for my freedom. First there are all the people who names begin with the letter J – which also stands for justice. So there is Johina, my beloved daughter. There is Joy Hurcombe, of the Save Shaker [Aamer] Campaign: for all these years she has stood up for me, and I am overwhelmed. There is Joanne MacInnes of We Stand with Shaker. And then there is Jane Ellison, my local MP. I know she is a Minister now, which means there are things she cannot do, but I know she has supported me all this time.

And there is also the Mail on Sunday, which has been campaigning for my release for years, and against the many injustices of Guantánamo since the month it first opened in January 2002. One of the first things I did when I was told I was coming home was to write an article for the paper to publish. I still hope it can be, but it has been held back by the military censor, and I don’t know if it will ever be cleared.

All these people need to be congratulated. The lawyers are doing a job that they swore to do. But these people who stood up for me all these years did not give up.

I say to them you did not do that wastefully. Your fight was for an innocent person. You did a great thing. May God reward you as you deserve for what you did. Our Prophet told us that if you do not thank people, you do not thank God. Words will never be enough, no matter what I say.

But for now, I am still detainee 239, and as I have so many times before, I am enduring abusive treatment. In turn I am protesting in the only way I can — through hunger strike. I am not going to stop this, and by the time I get home my condition will truly have deteriorated.

It started on August 3, when they came to me saying they wanted to check for tuberculosis. They have checked me for this many times before: they know I do not have it, but they said they were doing it to everyone. I told them: ‘Do the skin test’. They said, ‘No, we want blood’. I said, ‘Do the X-ray test’. ‘They said: ‘No, we want blood.’ I refused.

They demanded again. So finally they said they would bring the FCE [the Forcible Cell Extraction team, Guantánamo’s body-armoured specialist rapid reaction force, which has allegedly carried out hundreds of assaults on prisoners — Aamer included]. I said: ‘OK, bring the FCE’.

They came with the FCE. They tied me so freaking tight on the board when they forced me down. I shouted the legal formula — ‘My name is Shaker, I am telling you exactly that I do not want the blood test, I have the right to refuse it. Do you agree you are doing it by force?’

The nurse agreed she was taking it involuntarily. She was an oriental woman. They dragged my arm to one side, stuck in the needle and took four vials of my blood. I said that was too much. They took the blood, and sent me back to my cell.

Over the next two days, I discovered that nobody had blood taken but me. So they lied about doing a TB test on everyone. And even if they were singling me out, this does not explain why they needed four vials. Why did they take so much blood from me? And the TB test? They refused to tell me the result.

I quit eating from then on in protest. I lost 15lb the first week. Straight away they put me on the scales, not once but twice a week. I demanded: ‘Is this an experiment that you are doing on me?’ Last Tuesday I was 182lb. This Tuesday I was 174. Now, on Thursday, I am around 170.

Of course, everyone knows I am leaving. But I am only going to take what sustenance I need to keep alive, minimally alive. I will be very sick when I come back home. If anything happens to me before I do, it will be the Americans who are responsible. I am not going to do anything to myself. I know there are people who, even now, are working hard to keep me here.

I know there are people who do not want me ever to see the sun again. It means nothing that they have signed papers, as anything can happen before I get out. So if I die, it will be the full responsibility of the Americans.

The doctor came today [Thursday, October 1]. I told him: ‘Shame on you. If you have any shame you will never come by me.’ He brought a translator, a nurse, and an army paramedic to be witnesses, as he wanted to have witnesses that I was refusing whatever he came to say. I said: ‘You are the same doctor who was in Bagram, the same as in Kandahar and the same as every doctor in Guantánamo — I do not see the face, I see the uniform. You are a tool, you are not a true doctor. You want to write in your documents that you keep trying to help me but I refuse. If I die suddenly, you will say that I chose to die.’

Lately, I have become very interested in reading about Japanese war crimes in World War Two. The film ‘Unbroken‘ is about Louis Zamperini, an American captured by Japan. ‘They deprived us of our title to be prisoners of war so that they could do anything they wanted to us,’ he wrote then. ‘They enslaved us so that we were nothing.’

I could not believe this was 70 years ago. It was just the same as what the Americans have done to us — deprived us of the title of prisoners of war, and decided they can do what they want with us. The Americans treated us as badly as the Japanese did the Americans.

A few years after the war ended, the Americans forgave everyone and set their own Japanese prisoners free. They decided to forget about that time, as they wanted to be friends with Japan. Yet here we are at Guantánamo, 14 years later, and nobody is putting an end to all this.

I do not want to be a hero. I am less than a lot of people who suffered in this place. But all this time I stood for certain principles: for human rights, freedom of speech, and democracy. I cannot give up.

The irony is, I learnt to be this way from Americans. It was they who taught me to shout loudly if I want people to hear me. I went to America to learn this. When I was nine years old an American family from New York lived next to my house in Saudi Arabia. The father encouraged me to go to America to learn all those good things. My father said I should not go, so I said goodbye to him. He would not give me money to study. So I went to the US with $200 in my pocket. I worked hard. I had a bank account. I had a car. I did that by myself, inspired by the American way of life.

When I was kidnapped in Afghanistan at the end of 2001, I had a big smile on my face. The interrogator asked me why I was smiling. I told him, ‘Because you are Americans. You know I did nothing, so you’re going to send me home.’ How wrong I was. How much I have lost. But though I can barely grasp it, it seems that the belief I had then is finally going to come true.

Shaker Aamer’s recollections about Ibn al-Shaykh al-Libi

The Mail on Sunday introduced its section on Shaker Aamer’s recollections about Ibn al-Shaykh al-Libi by stating that his police statement “leads to one especially damning conclusion: that Britain must have known so-called intelligence that was used to justify the war in Iraq was based on evidence obtained under torture,” adding, “This conclusion will have grave implications for Tony Blair, his former Ministers, MI6, the Chilcot Inquiry and Scotland Yard. It also gives a chilling insight into why Aamer has been held so long in Guantánamo.”

As the Mail on Sunday described it, Shaker told the British detectives that “two British intelligence officers were present when Al-Libi was being abused, and when he was later rendered to Egypt,” a claim that, as far as I know, has not been made publicly before.

The newspaper also noted that al-Libi’s false confession — that Saddam Hussein “had supplied chemical and biological weapons to Al Qaeda terrorists, and trained them in their use,” came only after he was “locked in a tiny cage for more than 80 hours,” and was then “severely beaten.”

Shaker Aamer also told the detectives “how he was brought into a Bagram interrogation room where Al-Libi was present, tied to a chair,” because “[t]he interrogators apparently hoped that each man would give up information about the other, perhaps in the hope of securing more favourable treatment.”

In his statement, Shaker said, “I was a witness to the torture of Ibn al-Shaykh al-Libi in Bagram. His case seems to me to be particularly important, and my witnessing of it particularly relevant to my on-going detention. Because he was detained in November 2001, and I was one of the first five other prisoners in Bagram where he was being held, I was in a rather unique position as a witness to what was going on with him. He was there being abused at the same time I was. He was there being abused when the British came there. Indeed, I was taken into the room in the Bagram detention facility where he was being held. Clearly the fact that I was a witness to all this does not make the US want to let me free, for fear that I may be a witness to one of the most colossal mistakes of all those made in the last eleven years.”

The Mail on Sunday also explained that, since making his statement to the police, Shaker has also given further details to Clive Stafford Smith, who said that, “from his nearby cage, Aamer saw a coffin being taken into the interrogation room where he had seen Al-Libi. Later, he saw the coffin being taken out, and assumed the prisoner had died.”

He added that Shaker’s witnessing of these events “may well be the real reason why his release from Guantánamo has been delayed for so long.” As he put it, “Al-Libi’s torture and its disastrous consequences amount to the single most embarrassing event in the history of the war on terror.”

Ramzi Kassem describes breaking the news to Shaker of his impending release

It was not my first time walking up the dusty path to the gate of Camp Echo at Guantánamo. Over the past decade, in nearly forty trips to the prison, I’ve lost count of the number of times I’ve walked that way, heading to or from meetings with shackled clients.

But this was no ordinary client meeting. I had come to inform my client Shaker Aamer that, after fourteen years in captivity without charge, trial, or fair process, he was about to be set free and returned to his wife and their four children in Britain.

News had broken that morning that the U.S. Defense Secretary had forwarded notification to Congress of the U.S. government’s intent to transfer Shaker to Britain. Under U.S. law, that notification begins a thirty-day countdown. At the end of that period, around October 24th, the path will be clear to Shaker’s release. His return home could take place anytime on or after that date.

Still, the routine remained all too familiar. The soldiers riffled through my legal papers then ‘wanded’ me for metal contraband before escorting me through another set of clanking iron gates to one of the plywood shacks where attorney-client meetings take place in Guantánamo.

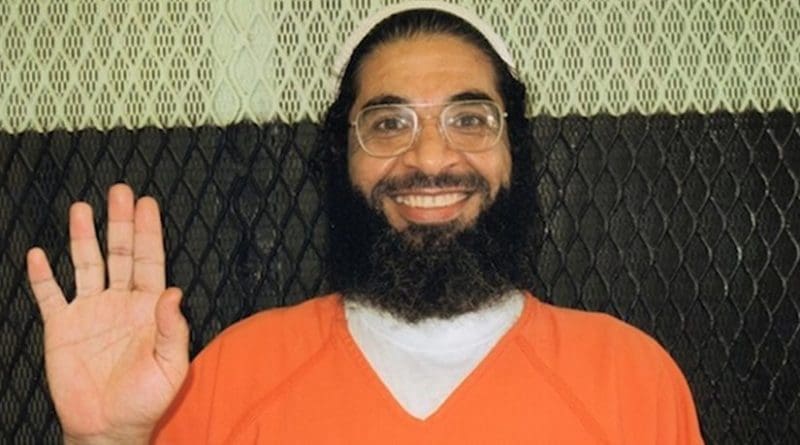

Shaker was sitting, shackled by one ankle to a steel loop jutting out of the shack’s flooring. He wore jumpsuit pants in signature Guantánamo orange. He had taken off the top, however, because of the tropical heat, and was in a sleeveless white undershirt. His beard thick and dark, his long hair braided neatly and resting over his right shoulder, Shaker also sported a knitted white Muslim prayer cap, off to the side. This was exactly how he wore his cap when we first met in that shack, almost four years earlier, in October 2011.

Shaker stood up to shake my hand and we exchanged customary holiday greetings as it was Eid al-Adha, the most important holiday on the Muslim calendar. I sat down, inhaled deeply, paused, and said, in Arabic: ‘Shaker, finally, the end of your ordeal seems near.’ I then explained that morning’s news and its implications as clearly as I could.

Shaker sat silently with a blank stare on his face. After a few, long seconds, he began to tell me about his prison-issued shoes, how they were falling apart, held together only by duct tape. He took off and held up the black sneakers, unraveling the tape. They were tattered and dismembered as a beggar’s. The Guantánamo prison administration had not replaced them since 2010.

It dawned on me that my news of his impending release didn’t register; it simply washed over him, leaving no trace. After fourteen endless years, the only normal reaction would be to grasp onto something he knew to be concrete and real: the problem of these shoes in this prison.

I decided to interrupt his disquisition about the shoes. ‘Shaker,’ I said, ‘please listen to me carefully.’ And I repeated everything I had shared earlier. Shaker looked at me, his eyes wide, and asked: ‘Are you being serious right now?’ Then an impossibly large smile lit up his face and his gaze suddenly grew distant. A door had finally swung open, and he was looking ahead at everything that lay beyond.

Laughing at his own earlier digression, Shaker quipped that the Guantánamo prison administration now had no choice but to issue him new shoes — they couldn’t possibly risk embarrassment by letting him return to the United Kingdom with these hideous things on his feet!

He also expressed hope that it would be a British plane — not an American military plane — that would take him home. The last thing Shaker wants is to relive his terrifying flight to Cuba over a decade ago, where he was chained in a painful position, blindfolded, ear-muffed, and cold.

Shaker shared with me that he hadn’t slept properly in almost an entire month, the uncertainty of his situation gnawing away at his rest. The night before our morning meeting, he had barely slept two hours.

In the morning, the soldiers moving him from his cellblock to Camp Echo insisted on conducting a groin search for the first time in weeks. One guard asked Shaker if he wanted to ‘refuse’ his legal meeting in order to avoid the humiliating search. Shaker wondered if the prison administration wanted to keep the news from him by preventing our meeting.

We spent the remainder of our time together contemplating Shaker’s return home. Overjoyed though he felt, like many past clients, Shaker was discovering that the prospect of life after Guantánamo is not free of worry. Naturally, Shaker is anxious as well. He knows that his reintegration into his family’s life and into society at large will be challenging at times.

Shaker and his family will need time and privacy to overcome that challenge and slowly begin to rebuild their lives together. Shaker hopes that the good people of Britain will understand his desire to avoid publicity as he takes his first tentative steps as a free man and embarks on the lengthy process of getting reacquainted with his loved ones.

Of course, Shaker is infinitely grateful to his supporters in Britain and beyond, and to his legal team, for all that they have done over these long years in the name of justice, and for everything they will continue to do to ensure his prompt return home. He hopes to thank everyone directly, in due time. But, once he is finally released, Shaker asks for everyone’s patience and forbearance as he and his family take the time they need to heal and adjust, away from the spotlight.

As I looked at Shaker and thought of all the years he had spent in captivity, all he had lost, the horrendous abuse he had survived, how mightily he had struggled to preserve his dignity, one thing became obvious. Shaker Aamer should get to leave Guantánamo and go home on his own terms. It’s the least we can do for him.