Will Mohammed Al-Qahtani’s Severe Mental Illness Secure His Release From Guantánamo? – OpEd

For anyone seeking a single story that is emblematic of the horrors of Guantánamo, the story of Mohammed al-Qahtani ought to be instructive.

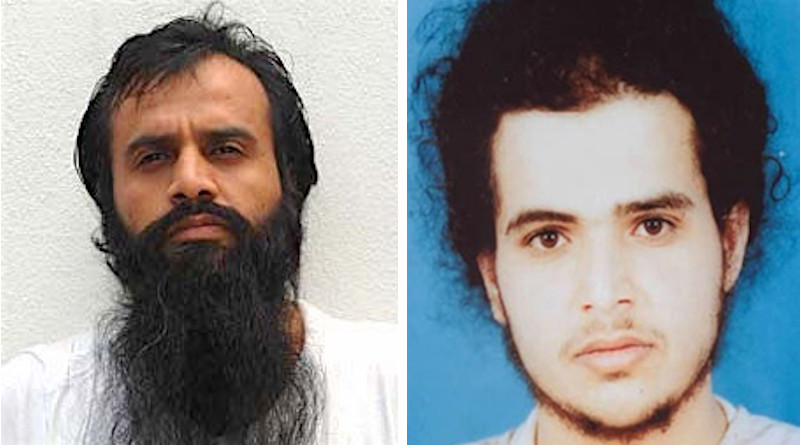

One of hundreds of prisoners seized in the chaos of Afghanistan after the US-led invasion in October 2001 and sent to Guantánamo after brutal treatment in US prisons in Afghanistan, al-Qahtani finally came to the attention of the US authorities in Guantánamo when it was assessed that he was the same man who had tried and failed to enter the US before the 9/11 attacks, and was presumed to have been intended to be the 20th hijacker.

He was then subjected to a horrible torture program, personally approved by then-defense secretary Donald Rumsfeld, which lasted for several months in late 2002, and which, as Murtaza Hussain explained for the Intercept in April 2018, involved him being subjected to “solitary confinement, sleep deprivation, extreme temperature and noise exposure, stress positions, forced nudity, body cavity searches, sexual assault and humiliation, beatings, strangling, threats of rendition, and water-boarding.” On two occasions he was hospitalized with a dangerously low heart rate.

The log of al-Qahtani’s torture is here, and it led to the only time in Guantánamo’s history when a senior government official acknowledged that a prisoner had been tortured. “We tortured Qahtani. His treatment met the legal definition of torture,” Susan Crawford, the convening authority for the military commission trial system at Guantánamo, told Bob Woodward just before George W. Bush left office, explaining why she had refused to refer his case for prosecution.

What no one discussed at the time — although US officials knew — was that al-Qahtani was also mentally ill. As one of his lawyers, Ramzi Kassem, a law professor at City University of New York, said, “The government knew from very early in his detention that this man was manifesting serious psychiatric conditions. As early as 2002 [before his torture], a senior FBI official reported observing ‘behavior consistent with extreme psychological trauma’ in Mr. Qahtani, like ‘talking to nonexistent people, reportedly hearing voices, crouching in a corner of the cell covered with a sheet for hours on end.’”

When al-Qahtani was eventually allowed to meet a lawyer (after the Supreme Court granted the prisoners habeas corpus rights in June 2004), the lawyers discovered that he had “documented mental health issues going back to the age of 8,” as Kassem explained, and that he had been committed to a mental health facility in Saudi Arabia in 2000.

The Intercept’s report coincided with a submission by his lawyers to the District Court in Washington, D.C., in which they sought to get the judge, Rosemary Collyer, to order the government “to ask for his current condition to be formally examined by a mixed medical commission, a group of neutral doctors intended to evaluate prisoners of war for repatriation.”

I wrote about that court submission here, and followed up in March this year, when, prior to her retirement, Judge Collyer ruled on the case, ordering the mixed medical commission to go ahead. Her ruling, as Carol Rosenberg explained for the New York Times, involved her spelling out that “she was granting a request” by al-Qahtani’s lawyers “to compel the United States to apply an Army regulation designed to protect prisoners of war and to create ‘a mixed medical commission’ made up of a medical officer from the US Army and two doctors from a neutral country chosen by the International Committee of the Red Cross and approved by the United States and Saudi Arabia.”

In August, Judge Ellen Huvelle, who was assigned the case after Judge Collyer’s retirement, reiterated the court’s commitment to securing a mixed medical commission for al-Qahtani, after the government appealed to the D.C. Circuit Court, and on September 29 the appeals court dealt another blow to the government, refusing to accept the government’s efforts to delay the ruling.

As the Center for Constitutional Rights explained in a press release, Ramzi Kassem said, “Mohammed al-Qahtani was already gravely mentally ill when he was taken into US custody and tortured. None of this is seriously disputed by the government so we hope that today’s ruling sends a message that it is high time for Mohammed’s ordeal to end and for the larger travesty at Guantánamo to conclude.”

For CCR, Shayana Kadidal said, “Our client has suffered from schizophrenia since his adolescence. The government has never seriously challenged that conclusion, nor could it. Today’s ruling means the military will have to break with its preferred habit of inertia and move this process forward towards a conclusion all parties acknowledge will result in a finding that Mohammed suffers from schizophrenia, and should be sent home to a psychiatric facility in Saudi Arabia.”

AS CCR further explained, “Mr. al-Qahtani suffers from serious mental and physical health conditions, including schizophrenia. Medical records prove that that incurable disorder long predates his imprisonment. In addition, he suffers from major depression and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) resulting from his systematic torture at Guantanamo beginning in 2002.”

CCR also explained that the motion for a mixed medical commission was filed in 2017, and medical experts have declared that, since it was first filed, al-Qahtani’s condition “has deteriorated to an alarming degree.” As CCR described it, “He suffers from an inability to control his behavior that is triggered by hallucinations, such as “screaming, being angry, throwing things, [and] taking off [his] clothes;” he has withdrawn from interacting with his family; and he has failed to attend meetings with his attorneys and then forgotten that he missed them.”

In the New York Times, Carol Rosenberg noted that Justice Department lawyers greeted the ruling with what seems to me to be a typically scaremongering over-reaction, warning that the first use at Guantánamo of a mixed medical commission “would be disruptive and unleash more requests by other prisoners.”

As Rosenberg described it, “The order has rattled the Defense Department, which considers the Guantánamo detention center its domain and any Red Cross role as advisory. The current prison commander, Rear Adm. Timothy C. Kuehhas, predicted in a court filing in April that the detainees would exploit the creation of a mixed medical commission ‘to undermine their health or injure themselves,’ to seek medical repatriation, and ‘jeopardize the safety of the guard force.’”

She added that “the three-judge panel at the circuit appeals court ruled that the decision to conduct a fact-finding in the context of a habeas corpus petition was not subject to review by the higher court,” with the judges — Karen LeCraft Henderson, Judith W. Rogers and David S. Tatel — adding that, “even if it was, the government did not demonstrate in its filings that conducting a mixed medical commission at Guantánamo ‘might have a ‘serious, perhaps irreparable, consequence.’”

Hopefully, the commission will now go ahead, and other prisoners — also with long-standing mental health issues — might also get to have the state of their mental health assessed, but no one should get too carried away with any enthusiasm that there will be a just resolution to al-Qahtani’s long-standing — and deteriorating — mental state.

Elsewhere in the court system, appointments made by Donald Trump have already started to poison any notion that the long injustice of Guantánamo can reach any kind of resolution in the courts, as a recent decision in the D.C. Circuit Court, led by a Trump appointee, Judge Neomi Rao, showed, when the court made an unprecedented — and alarming — decision that Guantánamo prisoners are not entitled to invoke the due process protections of the Constitution. And in the Supreme Court, of course, there is now a dangerous right-wing bias, with the Court unlikely to deal fairly with any Guantánamo case that makes its way to them, having worked its way through the lower courts.

And beyond all this, of course, is the fundamental lawlessness of Guantánamo, where the law has barely made itself felt over 18 years, where the legacy of torture still lives on, and where parts of the government remain as determined as ever that tortured prisoners — like Mohamed al-Qahtani, and like other men tortured in CIA “black sites” — should never be freed.