The ‘Crisis’ In Sri Lanka: Invented By Western Media – OpEd

By IDN

By Dr Palitha Kohona*

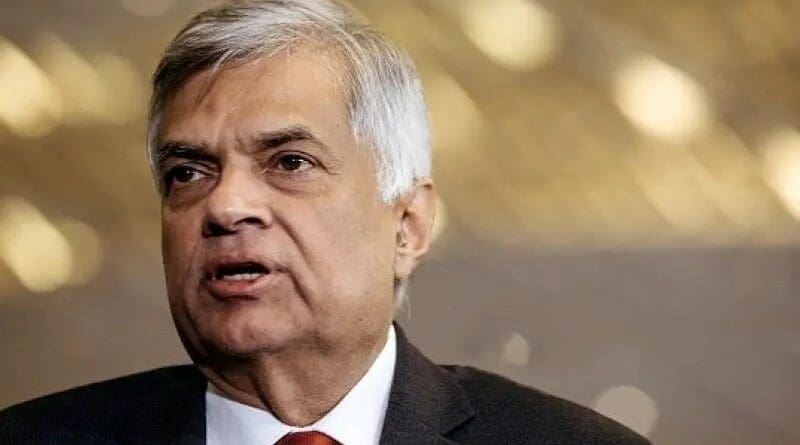

The change of Government in Sri Lanka, following the unceremonious sacking of Prime Minister Ranil Wickremasingha by President Maithripala Sirisena, has given rise to a crescendo of alarmist commentary in the Western media, which is slowly seeping in to the non-Western media as well. One after the other, the Western media outlets have taken a critical approach to the change and have begun to characterize the replacement of the Prime Minister as a “Crisis”.

Suave, comfortable in a European life style, fluent in the only European language he knows, English, neo liberal in thinking, and from an elite background, the former Prime Minister is fondly addressed as “Ranil” by the European diplomats and the dominant Western media representatives.

He moves in Western circles with ease and is the darling of the mainly Western funded NGOs. Ranil enjoys an easy relationship with the Occident, having cultivated individuals and institutions there over the years.

The sacking of Ranil was unexpected, caught the Western diplomats by surprise and they reacted with undiplomatic shock. It disrupted a securely established network of relations and convenient expectations. The discomfiture in this group was palpable. Certain heads will roll and promotion prospects of others will suffer in some diplomatic establishments of the West.

Being caught so totally unprepared is a reflection of the effectiveness with which Ranil and his cohorts managed the Western diplomatic community and Western media representatives along with the active concurrence of the mainly Western funded NGO community and resident American and European nationals.

They simply swallowed the government line, living in a make believe world that did not reflect real world of Sri Lankan politics, and were blissfully unaware of the gathering storm of popular resentment. Others appear to have just hidden their heads in the sand and fervently hoped that the suggestions of a brewing storm was just a bad dream.

In a strange use of terminology, the Western media has chosen to characterise Ranil’s sacking as demonstrating a “lack of respect for democratic institutions” such as the Parliament despite the reams of legal justification provided by experts and the explosion of popular support that followed for the action. It is probably a forlorn hope to expect them to tag the sacking by a fond color like the “Orange Revolution – Ukraine” or a season “Arab Spring”. Both of which enjoyed Western sponsorship, now quietly forgotten due to the mayhem that followed.

The irony is that the same commentators never expressed their derision in such strong terms when local government elections kept being postponed sine die, when a parliamentary report on the scandalous Central Bank bond scam by Ranil’s close friend Arjuna Mahendran was sidelined by a prorogation of parliament, or when Ranil engaged in unruly and unparliamentary behaviour in Parliament when confronted with this issue.

The agonised concern of the West would have sounded more convincing had there been a more even handed approach and the commentary of Western diplomats would have found more sympathetic listeners. There are lessons for both sides here.

But more importantly, consistent with established diplomatic practice, it would have been more appropriate if the Western diplomatic community and the UN representative had been more circumspect and even handed in expressing their support for democracy rather than instinctively rushing to endorse only Ranil as the guardian of democracy. In this instance, the measured tones of the Indian and Australian response suggests a greater appreciation of the real situation.

A diplomat needs to read the tea leaves of domestic politics more cleverly. There was little room for speculation or for error in the case of Sri Lanka unless it was self-induced.

The vast majority of the population of Sri Lanka was clearly hoping for a change in the leadership of the country. When the party owing allegiance to Mahinda Rajapaksa won over 239 of the 340 local government bodies contested in February the message was stark. The huge and adoring crowds that flocked to listen to Mahinda conveyed an obvious message.

In September, a peoples’ march ‘Janabalayaa Kolambata,’ organized by the youth wing of Mahinda Rajapaksa’s SLPP brought over 300,000 people from across the country to Colombo, demanding an immediate dissolution of the government.

A similar crowd gathered in pouring rain when the President and his new Prime Minister addressed them in front of the Parliament on October 5. University students, industrial unions, farmers, even university professors and doctors had been mounting protest action against government economic policies.

The strikes affecting various parts of the economy were to a considerable extent a reflection of the disaffection felt by the people. The voices of the disgruntled had reached a crescendo but appears to have by passed the Western diplomatic community.

The heads of the highly influential Buddhist establishment, including the prelates in Kandy, and the minority Catholic establishment had forcefully reflected the popular sentiment. Sadly, either the West chose to ignore the clear signs on the ground or simply misread the signs.

Within an hour of the announcement of the sacking of Ranil, Sri Lankan media broadcast images of people lighting celebratory fire crackers across the country including in the Tamil-dominated Jaffna which is still trying to recover from the devastation of the terrorist conflict.

Consistent with the traditional form of celebrating victory, many businesses provided milk rice to passersby along main roads. Leaders of business had already begun to express their dissatisfaction with Ranil’s lack of firm leadership, the absence of direction in economic policies, the implementation of policies without much consultation with the key stake holders, the erratic policy implementation, the lack of confidence in the business community, etc. The signs were obvious, only if one wished to take note.

The President articulated many of these sentiments a few days after the sacking. He highlighted Ranil’s inability to connect with the common people and his disrespect for those outside a small circle of the Colombo-based elite, and his disregard for the country’s sovereignty and his tendency to favour foreign business over locals.

Ranil’s lack of enthusiasm to bring the Central Bank scammers to justice had annoyed the President who was elected on a platform of introducing good governance. He obviously felt aggrieved by Ranil’s supercilious attitude towards him as President.

The President said: “Mr Ranil Wickremesinghe’s political conduct was unbecoming of civilized politics and belittled the victory achieved risking my life in 2015. I believe that Mr Wickremesinghe and his group of closest friends, who belonged to a privileged class and did not understand the pulse of the people conducted themselves as if shaping the future of the country was a fun game they played.”

The President was more scathing and critical in his comments at the address on October 5 when he said: “Corruption and fraud spread widely in the country.”

PM Wickremasinghe, was increasingly seen as a puppet of the West, particularly the U.S., supporting their geo-political agenda in Asia. Sri Lanka has a history of rebellious politics and being perceived as pro West is not necessarily a guarantee of popular support.

The West also has been trumpeting the dangers posed by Rajapaksa, allegedly an ally of China. He has also been described as authoritarian and power hungry. This may have gone down well with certain sections of the Indian establishment but not necessarily with the vast majority of Sri Lankans who entertain historical sympathies for China.

While it is true that Rajapaksa obtained significant loans from China to fund development projects, to characterise him as pro-China is a convenient excuse for not understanding him well or simply succumbing to assessments provided by Ranil and the NGO community.

During his presidency, Rajapaksa turned to China for funding assistance only after being snubbed by India and international funding agencies. The EU had withdrawn the GSP Plus facility from Sri Lanka and the U.S. had pulled the Millennium Challenge Account.

After ending the terrorist inspired conflict Rajapaksa was in a hurry to develop the country and China was willing to help. It is important to remember that while Rajapaksa borrowed from China to fund development projects, (ONLY 8% of Sri Lanka’s external debt is owed to China) that also after lengthy negotiations, it was Ranil who injudiciously gave the port of Hambanthota on a 99 year lease to Chinese companies.

Rajapaksa could hardly be described as anti-West when his choice for advanced studies for two of his sons was England (and not China) and three of his brothers have homes in the U.S. He visited the U.S. almost every year when he was President.

The narrative purveyed in the Western media characterises the situation in Sri Lanka as a “crisis”. This reflects the views of mainly Western funded NGOS and of Ranil.

“The current constitutional crisis is unprecedented in that Sri Lanka has never had the legality and legitimacy of its government called into question in this way. We regret and deplore the course of action that has resulted in this unnecessary crisis and democratic backsliding,” the Centre for Policy Alternatives, a Western funded local NGO said in a statement.

But those who make this assessment have not challenged the sacking before the courts which incidentally consist predominantly of judges appointed in the last three years, during Ranil’s tenure as Prime Minister. Now the Speaker of the Parliament, perhaps egged on by Ranil’s party and encouraged by the stance taken by the West, has refused to recognize the new Prime Minister.

The U.S., the UK and some other European countries have publicly articulated concerns about Russian and even Chinese interference in their domestic electoral processes, but the behaviour of their own missions in Colombo has not contributed to enhancing their reputations with the majority of the people. The contradiction looms large to all observers.

Again this might be a case of misreading the mood of the majority or simply dismissing the wishes of the majority despite all their purported commitment to championing democracy. Western ambassadors have met publicly with the ousted PM, Ranil, NGOs and opposition groups and issued statements from their capitals calling for the “Immediate convening” of parliament and “restoration” of democracy. Many in Sri Lanka have queried the propriety of such blatant interposition in the domestic political processes.

During a meeting with the President on October 30, the EU Ambassador Tung-Lai Margue warned that if democratic norms and constitutional provisions are not observed in handling the on-going political crisis in Sri Lanka, the EU may consider withdrawing the trade concessions the island nation enjoys under the General System of Preferences Plus (GSP Plus).

A similar threat by Japan and the U.S. has been reported in the pro-Western media. One notes an unfortunate return to the days when the West insensitively threatened and pulled out financial concessions from the previous Rajapaksa administration forcing it to reluctantly move further towards China.

There were also statements demanding that Sri Lanka abide by the Resolutions adopted by the UN Human Rights Council on Sri Lanka, especially the much derided Res 30/1, despite almost the entire country having objected to its provisions and some even suggesting that the then Foreign Minister, Mangala Samaraweera, who cosponsored it despite the overt opposition of the Ambassador in Geneva, be hauled before the courts for treason. One is confused by the approach of the U.S. which has recently, on the basis of national interest, denounced even solemnly concluded treaties.

Sirisena has quietly told the Western envoys that they appeared to be “unaware of the pulse of the people”. The President has advised the envoys to understand the common man’s thinking, and that the people are with him. He has also told the envoys that it is best to leave the governance of Sri Lanka to Sri Lankans and that the government and the people of Sri Lanka know best what is good for them.

*Ambassador Dr Palitha Kohona, Former Permanent Representative of Sri Lanka to the United Nations.

End of classles politics inAsia.