The Bank Of Japan Shrinks The Pocket Money Of Japanese ‘Salarymen’ – OpEd

By MISES

By Gunther Schnabl and Taiki Murai*

In December 2012, Japan’s Prime Minister Shinzo Abe set out three arrows in his quiver to pull the country out of the more than 20 years lasting stagnation. Immense purchases of assets by the Bank of Japan, huge government spending programs and structural reforms should deliver a sustained recovery to the Japanese people. In the meantime, it is becoming evident that so-called Abenomics is – despite buoyant stock prices – a damp squib. Inter alia, this is indicated by the pocket money of Japanese “salarymen,” male white-collar workers who commute day-to-day in dark suits by stuffed trains to the central business districts of the Tokyo metropolitan area.

Nikkei 225 and Pocket Money of Japanese ‘Salarymen’

Traditionally in Japan the men earn the money and the wives manage the household. A Japanese proverb says that the wife controls the purse strings, with the women being quite generous. In 2019, the Japanese male white-collar workers still received on average 36,747 yen (almost 340 US dollars) per month for bars, restaurants and other leisure activities in which their wives are typically not involved.

But the good times are long gone.

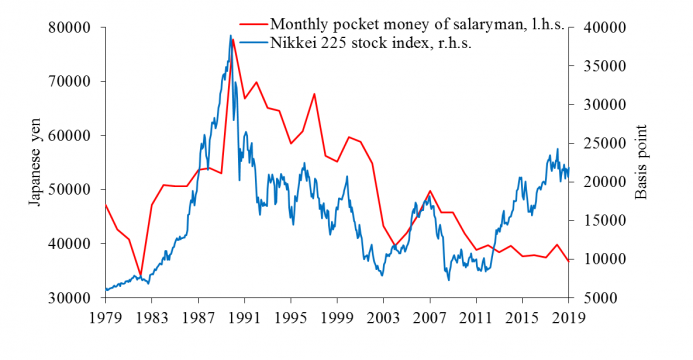

In the second half of the 1980s, when sharp interest-rate cuts by the Bank of Japan inflated during the so-called “bubble economy,” stock and real estate prices – as well as wages and bonuses – the pocket money of salarymen skyrocketed. Between 1985 and 1990, both stock prices and pocket money grew by about 50 percent each (see chart). At the top of the bubble in 1989, pocket money averaged almost 80,000 yen (a good 600 US dollars) per month. At that time, drinking every night in the bars without limits symbolized the exuberance.

Since the bursting of the Japanese bubble in the early 1990s, both stock prices and pocket money have steadily declined. By the time Abenomics started in January 2013, stock prices had fallen by 73 percent and the pocket money of salarymen fell by 51 percent. The efforts of the Bank of Japan to cushion the crisis by cutting interest rates to zero and pioneering on unconventional monetary policy measures could not prevent Japanese housewives from pulling the string of the purses tighter and tighter. The wives seem to have been guided by both the doldrums on financial markets, and the gradually declining wages since the 1998 financial crisis.

Thus, the pocket money indicator also says something about the success of Abenomics from the viewpoint of the ordinary Japanese people. Since Haruhiko Kuroda took office as president in March 2013, the Bank of Japan has bought government bonds, corporate debt, ETFs and J-REITs amounting to 405,000,000,000,000 yen (approx. 3,700,000,000,000 dollars) to jumpstart the Japanese economy. Nevertheless, Kuroda could not convince the Japanese housewives to loosen the purse strings. While the Abenomics have, to date, boosted the Nikkei stock index by 130 percent, the pocket money continued decreasing near to the level of 37 years ago (34,100 yen in 1982). This indicates that in the sentiment of the Japanese people the post-bubble crisis has never ended up to the present.

This could mean that a few rich Japanese, who are holding large amounts of stocks and other assets, may be the only ones who benefited from the new stock price inflation. In contrast, the majority of Japanese continues to tighten their belts, as real wages continue to fall in the face of sluggish productivity gains. This points to the unjust distribution effects of the Abenomics, which make the rich richer and all others poorer. This phenomenon cannot only be observed in Japan, but also in the euro area where Christine Lagarde is expected to follow the Japanese monetary policy pattern.

*About the author: Gunther Schnabl is a professor of international economics and economic policy in the department of economics at Leipzig University, Germany.

Source: This article was published by the MISES Institute