Despite Parleys, Peace For Ordinary Afghans Seems So Far Away – Analysis

By Chayanika Saxena*

Having passed through what can be claimed as two successful rounds of international parleys, the Quadrilateral Coordination Group (QCG) of Afghanistan, China, Pakistan and the United States on Afghan Peace and Reconciliation process, and an informal but highly critical Doha Dialogue on Peace and Security in Afghanistan that could manage to get the political office of Taliban on board, it can be said that the process of reconciliation looks rather promising this time around. But even as the forces of peace and reconciliation might have been set in motion with greater effect than they had been in the recent past, a question that continues to riddle the current edition of talks is: how long will this round last?

The concern for ‘durable peace’ which is on the minds (or, let us believe that it is so) of all the participants who are a part of the renewed attempts, certainly sets a daunting challenge that requires more than just talking-shops to be instituted every now and then. Certainly, talks do lead to action, but the current round of ‘jaw-jaw’ might not be enough for a country that stares at another ‘spring offensive’ debilitating it further.

With a day to go before the third round of the Quadrilateral talks is held in Islamabad, it becomes critical to delineate what can possibly be the domestic accelerators and decelerators to the efforts underway. In doing so, it is critical to underscore that the peace and reconciliation process that has apparently got the whole world concerned is ultimately an Afghan enterprise. As the joint statement produced at the end of the first round of QCG (held on 11 January 2016) too had mentioned, the international bolstering is just that- a support; the process of reconciliation and the establishment of peace in Afghanistan has to be both Afghan-led and Afghan-owned. Thus, given the centrality of the domestic factors in the carving of this edition of peace talks, it becomes pertinent to focus on the enablers and challenges that the home-setup of Afghanistan can throw at the fragile peace process.

Faced by numerous challenges that are of national and trans-national nature, it would perhaps be comforting to be reminded that the desire for peace rides high among the common masses of Afghanistan.

Here it becomes instructive to note here that as a process, reconciliation is both top-down and bottom-up in its nature and that general local willingness and acceptance to the process matters as much, or perhaps, more in executing and sustaining the process of reconciliation. Affected by a fledgling economy, unabating political confusion and chaos and an international environment that is clamoring the quid-pro-quo principle on all its investments like never before, people of Afghanistan are convinced that it is high time that peace becomes not an intermittent but a permanent reality for them.

Despondent with the prevailing conditions and wanting a resolution, people of Afghanistan have arrived at what can be described in the literary metaphor as the ‘tipping point’. While the circumstances are on no scale small or minor, but they have certainly reached a stage from where a large change- and which is peace- appears to be the only development required and possible. In strict academic terms, this ‘tipping point’ has been called by William Zartman as ‘ripe moment’. A situation which sets in when a conflict is still going on, ‘ripe moment’ is essentially a stage of ‘mutually hurting stalemate’ when the parties to the conflict find themselves in a painful deadlock and where escalation of violence to achieve victory appears to be impracticable and even impossible.

But, where the masses are convinced that it is time to move out of the hurting stalemate that has set in, the question is whether the parties to the negotiation- the Afghan government and Taliban- see the prevailing situation as ripe enough for peace to be ushered in. The answer to this vexed question appears to be in both affirmative and negative at the same time.

Yes, the present edition of peace talks do speak in a tenor of confidence about giving peace a chance- after all, the third round would be underway very soon. But, where this confidence does take a blow are the domestic circumstances that may not be so much disposed in favor of arresting the spiraling violence affecting the country.

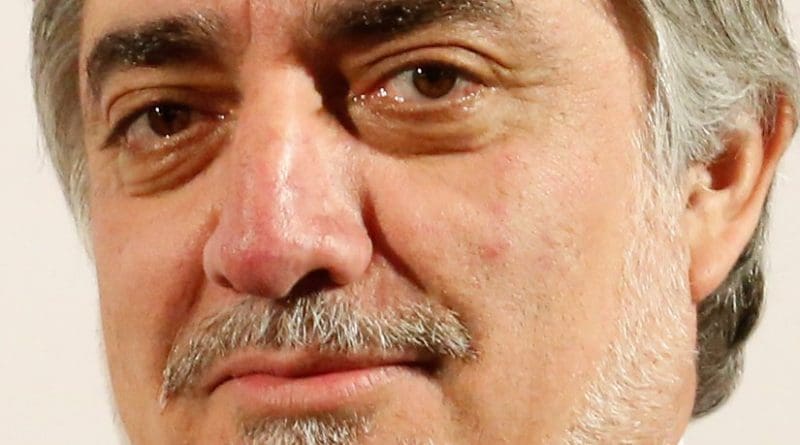

To begin with, the legitimate political front in Afghanistan, and which is the National Unity Government (NUG), is a divided house. While there is no denying that this dual-headed government does want to negotiate peace for the country and its people, just about how it wants to achieve the same has got it being pulled in opposite directions. Even as the regional and international forces are dissuading Kabul from keeping any preconditions to the talks, however the internal rumblings are of a kind that are not letting the two leaders look eye-to-eye on how to deal with Taliban. Although both, Ashraf Ghani and Abdullah Abdullah are convinced- as is the whole of Afghanistan- that Taliban will have to renounce violence to be considered as committed partners in the peace process, it is the terms of subsequent participation that have become the source of discord.

The Abdullah-led contingent within the government and the supporters outside are reluctant to cede any space to Taliban within the current political setup of the country. Believing that this insurgent movement is yet to prove its credibility and commitment towards abandoning its violent and parochial approach to dealing with the issues confronting the country, the CEO has consigned the possibility of a political negotiation with Taliban to the realm of future.

While not disagreeing with the description that the CEO-band has accorded to Taliban, the Ghani camp however, is not shying away from providing planks for political representation to this insurgent group right away. In fact, at the time when governmental infighting over the distribution of ministerial berths was at its peak- in the months after NUG was instituted (September 2014)- reports were rife about members of the political office of Taliban being given berths within the new establishment. Given that the process of reconciliation- at least theoretically- advises ‘reintegration’ for achieving sustainable results, the real practice of these tenets in the absence of agreement on political negotiations with Taliban makes it look like a far-off cry.

Apart from the friction between the two heads, those occupying the immediate (such as Gen. Dostum) and lower rungs within the national government and those wielding power the provinces (such as Ata Noor) might not be ready advocates for political reintegration of Taliban into the Afghan mainstream either.

Much like their ‘legitimate’ political challenger, the ‘shadow’ government of Taliban is now a show of many shadows. Ever since the death of its spiritual leader, Mullah Mohammad Omar was confirmed the last year, the war of succession within Taliban has come out in the open and so much so that the movement which had been known for its unity is now a fractured house within, with some 3-4 splinter groups contesting it ideologically and physically from outside.

While the new leader of Taliban, Mullah Akhtar Mansour has been able to quell a lot of dissension – by force and otherwise – and has managed to score a lot of strategic victories – (temporary) re-capture of Kunduz, Musa Qala, etc. – it cannot no longer deny that they have just too many masters now. With each side calling itself the ‘true’ version of the Islamic Emirate – which is what Taliban calls its government-in-exile- the infighting within Taliban implies that there will be variety of responses to the peace process – from compliance to its outright discarding.

Apart from sieving the talking-Taliban from the shooting-Taliban – which in itself is a grave problem as reconciliation is not possible without getting everyone on the same page – one of the biggest obstacles that remain to the successful conduct and execution of the peace process are the preconditions Taliban have placed. From demanding that its name be pulled down from the list of internationally proscribed outfits, that its leaders’ assets be de-frozen and that they be granted freedom of movement, Taliban continues to be unyielding so far as the acceptance of international presence in Afghanistan and its current constitution are concerned.

Wanting that the international forces pack their bags and leave and that changes be made to the existing constitution to get it more in sync with its interpretation of the Sharia law, the Masour-led Taliban, while open to political negotiation with the current Afghan government, is almost adamant on the points mentioned above.

To add to an incorrigible Taliban, that now has some equally unrelenting offshoots which it does not have any control over, the rising threat of the Islamic State – which interestingly the former denounces as uncouth and alien – has made the peace process murkier domestically. With their ambitions that cross the current nation-state boundaries of many countries, including India, the envisaged vilayet (district) of Khorasan of the Islamic Caliphate will be a bigger hindrance for the peace process to materialize.

The time may be ripe for some and may not be for others, but peace in Afghanistan is certainly the need of the hour for every ordinary Afghan. The international prodding aside, it is the people of Afghanistan who can be the most effective force, forcing change on both the sides of the conflict, the Afghan government and Taliban, a conflict in which they have been the biggest casualty.

*Chayanika Saxena is a Research Associate at the Society for Policy Studies, New Delhi. She can be reached at: [email protected]

Any Country that has big money in the middle east and doesn’t control thier radicals…(killers of non believers) should get NO “financial assistance” from the U.S. Either you clean up your radicals or you are against the world!