COVID-19: Quality Shock To Globalization – Analysis

Too many governments have made a devil’s compact with globalization – prioritizing speed and quantity of economic growth over quality.

By Stephen Roach*

With financial markets reeling in the face of a global pandemic, fear and panic have pushed the world to the brink of another crisis. For investors, it was a classic Wylie Coyote moment. Asset prices had been surging just as an increasingly vulnerable global economy was hit with the devastating supply shock of COVID-19.

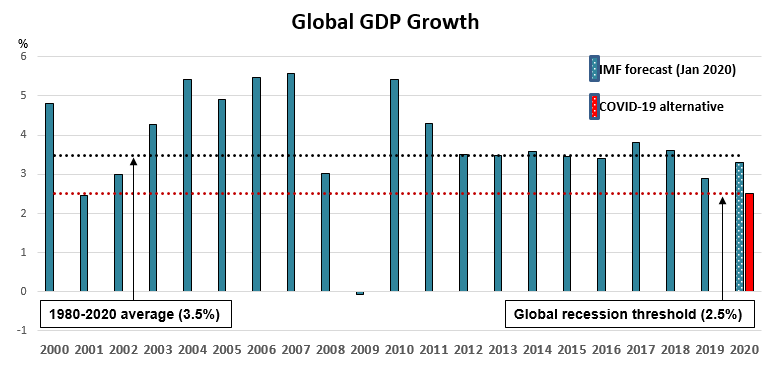

Predictably, in the pre-virus days of froth, many investors ignored the economic warning signs. In early January, the International Monetary Fund lowered its estimate for world GDP growth in 2019 to just 2.9 percent – the weakest year since 2009 and only 0.4 percentage point above the 2.5 percent global recession threshold. Moreover, the Japanese economy contracted at a 6.3 percent rate in the final period of last year, likely to be worse after revisions, on the heels of yet another consumption tax hike. And industrial activity weakened sharply in Germany and France.

And now comes a full-blown China shock – ironically, also occurring in the aftermath of 6 percent Chinese GDP growth in the fourth quarter of 2019, the slowest pace in 27 years. Weakening economies, whether it is China or another country, are less equipped to cope with a shock than strengthening economies. That points to an important distinction between a booming Chinese economy that was growing by 10 percent in 2003 when it was hit by Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome, SARS, and today’s slower growing and far more vulnerable economy.

Based on daily tracking of energy usage and transportation activity, in conjunction with a record plunge of purchasing managers’ sentiment in both manufacturing and services just reported for February, there is good reason to believe that the Chinese economy, the world’s largest economy by purchasing power parity, is contracting during the current quarter, possibly quite sharply. Not only does that imply its annual growth target of around 6 percent is in tatters, but it suggests an increasingly China-centric global economy is now in recession.

Yes, the US economy looks good by comparison. But real GDP growth of just 2.1 percent in the final period of 2019 hardly qualifies as a boom. The United States also lacks the cushion of resilience required to withstand the global shock now unfolding. As former US Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan stressed long ago, the US economy should never be thought of as “an oasis of prosperity” in an otherwise weak world.

Like investors, policymakers have also been blindsided. This is a supply shock – not a demand shock that can be rectified with monetary stimulus. Yet, despite having little ammunition to deploy, central banks are reopening their timeworn playbook. That might soothe battered financial markets, but will do little to address the physical constraints on real economic activity coming from draconian quarantines, travel restrictions and fears of assembly in public places.

While traditional monetary stimulus is unlikely to temper downside pressures on real activity, it could certainly provide a boost following containment of COVID-19. When that occurs is anyone’s guess. There may be some signs of a peaking of the infection rate at ground zero – China’s Hubei Province – but that is far from the case elsewhere around the world. At the same time, it is important to stress the lags between the disease infection curve and adverse economic impacts stemming from disease containment efforts. The very last thing that China or any other public health authority wants to do is to be lulled into a premature relaxation of disease containment just to restart economic growth engines. That might trigger a relapse that could well intensify the echo effects of this pandemic.

This underscores what could well be the toughest dilemma for globalization – the tradeoff between the quantity and quality of economic growth. The economic case for globalization is both simple and powerful. It rests on the combination of job creation and poverty reduction that support producers in the developing world and the efficiency solutions that lead to lower prices, boosting consumer purchasing power in the developed world. This ultimate win-win maximizes the quantity dimension of global growth – the faster the rate of expansion, the greater the presumed benefits to producers and consumers alike.

Shocks like COVID-19, however, unmask compromises that have been made on the quality side of the global growth equation. China’s healthcare insurance strategy is a case in point, where the government has long focused on maximizing coverage rather than on expanding benefits. At the same time, employment in China’s healthcare services industry accounts for just 5 percent of private urban employment versus 13.5 percent in the United States. This leaves China not only ill-equipped to deal with the mounting medical needs of a rapidly aging population, but also without the healthcare infrastructure required to contain an epidemic like the one now at hand.

The good news is that China has been far more transparent about the COVID-19 outbreak than was the case 17 years ago when the government went into denial for several months over SARS. This time, reporting delays were considerably shorter, and Chinese health officials, operating through the China Information System for Disease Control and Prevention, established after SARS, were quick to share the virus genome with the World Health Organization. The bad news is that China’s fragmented CDC was designed to track existing diseases rather than identify new outbreaks. Moreover, the apparent origins of COVID-19 – possibly bat hosts infecting wet wild animal markets – are strikingly similar to those that sparked SARS almost two decades ago. With the underbelly of its culture continuing to take precedent over modernization, China has squandered a painful learning experience.

China’s healthcare deficiencies, in conjunction with an equally glaring shortfall of unfunded pension liabilities, underscore the chronic gap in its social safety net. In response, households are predisposed toward precautionary saving, which, in turn, constrains growth in private consumption. The outbreak of COVID-19 undoubtedly reinforces this fear of an uncertain future, posing yet another obstacle to the national strategy of consumer-led rebalancing.

All of this points to one of the most uncomfortable truths of globalization. China, as the world’s largest producer, enjoyed a competitive edge, in part because it under-invested in its social safety net and avoided building those costs into product prices. The United States, as the world’s largest consumer, tilted its economy toward excess consumption, in part because it could expand its household sector purchasing power by buying cheaper goods made in China and more recently by China-centric global value chains.

This is the devil’s compact of globalization – maximizing the speed, or quantity, of economic growth while under-investing in the quality dimension of the growth experience. The same is the case with respect to climate change – an equally glaring deficiency on the quality side of the growth equation stemming from chronic under-investment in environmental protection.

While it is easy to pin the blame on China for avoiding its own safety net imperatives, others are equally guilty. By withdrawing from the Paris Agreement on Climate Change, reversing auto emissions standards, boosting support to coal mining and attempting to cut the budget for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the United States under the Trump Administration is also opting for the quantity of economic growth over quality. Can the confluence of a pandemic, a financial crash, and an unexpected global recession alter this tradeoff? The fate of globalization hangs in the balance, but so, too, does the human condition.

*Stephen Roach, a faculty member at Yale University and former chairman of Morgan Stanley Asia, is author of Unbalanced: The Codependency of America and China, published by Yale University Press.

The phenomenon of the Tower of Babel is recurring — this time viruses, not languages, scattering the builders of the towers.