Contract Dispute With Kazakhstan Flashes Warnings For Russia’s Legendary Spaceport – Analysis

By RFE RL

By Mike Eckel

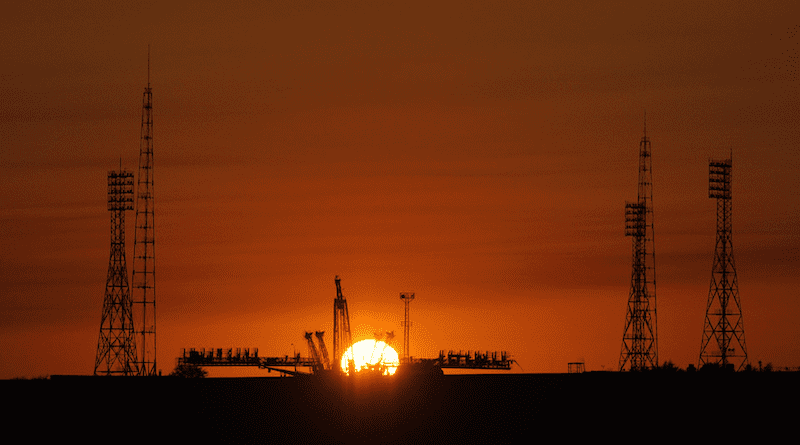

(RFE/RL) — For nearly seven decades, Baikonur has been synonymous with the Soviet and Russian space programs.

The sprawling complex on the barren steppe of southern Kazakhstan has hurled hundreds of rockets — and ballistic missiles — into space, playing a part in some of history’s greatest spaceflight achievements: Sputnik, the world’s first satellite; Yuri Gagarin, the first human in space.

The complex survived the Soviet collapse, endured the economic chaos of post-Soviet Russia, and then helped position the Russian space agency now known as Roskosmos as a leader in continued space exploration.

The sun, however, may be finally setting on Baikonur. For Russia, anyway.

At issue is an arcane contract dispute between Roskosmos, which pays Kazakhstan around $115 million annually to lease the complex, and a Kazakh company that is partnering with Roskosmos to build a new, multibillion-dollar launch facility called Zenit-M.

Kazakh authorities have seized the assets of Roskosmos’s main operator at Baikonur, citing unpaid debts, and are demanding $26 million. Russian officials have made a $220 million counterclaim.

Without the Zenit-M complex, Russia won’t be able to launch the Soyuz-5, a next-generation rocket that Moscow hopes will replace the stalwart Proton-M. The Proton-M uses a highly toxic fuel that Kazakhstan has complained for years has polluted the landscape.

Without the Soyuz-5 rocket, Russia won’t be able to raise badly needed revenue from commercial satellite launches, a business in which Roskosmos had enjoyed some success until the invasion of Ukraine in 2022.

“It’s the latest symptom of Russia’s continual decline as far as their status as a space power,” said Bruce McClintock, a former defense attache at the U.S. Embassy in Moscow and senior researcher on space policy at the RAND Corporation, a U.S. think tank.

“I don’t think Russia is going to lose access to the Baikonur launches in the near term — maybe in the long term,” he said.

“I think the future of Baikonur looks very bleak,” said Bart Hendrickx, a Belgium-based expert and longtime observer of the Soviet and Russian space programs. “Soyuz-5 looks like the only project that can keep Baikonur alive beyond 2030,” he said. “So if these recent events would jeopardize the future of that project, then yes, that would be a big deal.”

“The situation is quite serious,” said Nurlan Aselkan, editor in chief and publisher of the Kazakh magazine Space Research And Technology. “The situation at Baikonur is turning from a stable one — if sluggish, let’s say — into a problematic one that needs to be resolved.”

Vexed At Vostochny

The seeds for Russia losing Baikonur were planted with the 1991 Soviet breakup, and the question of what to do with the world’s largest space complex, which — for Russia — was suddenly in a foreign country.

For the Russian heirs to the Soviet space legacy, keeping Baikonur’s infrastructure intact was paramount. In 1994, Moscow signed a 50-year lease with the Kazakh government that was later extended until 2050.

Russian officials also realized they needed a viable alternative. A long-standing facility at Plesetsk in the Arkhangelsk region catered mainly to military satellite launches, due to its northern latitude. Plans were hatched in the 1990s to build a new spaceport in the Amur region in the Far East: Vostochny.

With the growth in commercial-satellite launches, Russia capitalized on its reputation for reliable, low-cost rockets, garnering nearly $10 billion in revenue over the past 25 years, according to one estimate.

In 2015, the Russian space program, a mishmash of engineering studios, research laboratories, manufacturing facilities, and related operations, was reorganized and put under a single government entity: Roskosmos. A bombastic former deputy prime minister and ambassador to NATO, Dmitry Rogozin, was named director.

The U.S. space agency NASA had partnered with Roskosmos since the 1990s, and the two agencies worked side-by-side to build and operate the International Space Station. The Russian program got a further boost in 2011, when the United States grounded its space-shuttle fleet, forcing it to rely solely on Russian vehicles to get people and cargo back and forth to the station. NASA paid up to $100 million per ride.

Those launches all occurred at Baikonur.

Construction at Vostochny began in 2011. The project slid into a swamp of cost overruns and endemic corruption, with the costs now estimated at $7.6 billion and climbing. The first launch, a satellite, was delayed by one year until 2016; completion, set for 2018, has been pushed back repeatedly. Of the 10 successful launches conducted to date, none have been manned.

Dozens of people, meanwhile, have been investigated for embezzlement and theft. Workers have gone on strike at least once for unpaid wages.

In 2021, the top Russian auditor said that inspectors had turned up 30 billion rubles ($400 million) in financial irregularities at the agency in 2020.

A Star-Crossed Space Agency

After Russia seized Ukraine’s Crimean Peninsula in 2014, Western countries, including the United States, began placing sanctions on Russian companies and top officials.

Roskosmos’s reputation was further dented by a series of mishaps and misadventures, including a still-unexplained man-made hole found on a Russian-built module at the station, an emergency landing of crew members returning to Earth, and a scandal involving the demotion of a respected cosmonaut.

A 2021 Russian military test of an anti-satellite weapon, which spewed debris into a high-velocity orbit around Earth, potentially endangering the station, didn’t help matters.

Roskosmos lost its monopoly on space-station transport in 2020, when the private U.S. company SpaceX delivered astronauts to the station. Other private companies are also joining the market.

The most recent mishap occurred in December, when a Soyuz capsule that was supposed to ferry two Russians and an American back to Earth sprang a leak. The incident forced NASA and Roskosmos officials to extend the trio’s stay on the station and send up an emergency replacement capsule.

The damaged capsule was sent back to Earth, landing in Kazakhstan on March 28.

And then there’s the rocket fuel.

Fatal Fuel

Russian, Kazakh, and Western scientists have studied the hazards of the toxic rocket fuel, which has showed up in soils in parts of northern Kazakhstan. In the early days of the Soviet space program, officials did not publicly report accidents or contamination. One such event that occurred in 1960, killing 126 people, mainly due to exposure to the toxic fuel, was kept secret until the Soviet collapse.

In 2004, Russia had planned to replace its Proton rocket series with a more environmentally friendly model by 2014.

The effort gained new urgency after 2013, when a Proton-M rocket carrying three satellites blew up minutes after launch from Baikonur, spewing toxic fuel, which is called heptyl.

Kazakh officials were outraged and imposed a temporary ban. Russia agreed to phase out use of the Proton rocket at Baikonur by 2025. The Soyuz rockets used to ferry equipment and personnel to the space station use a different fuel mixture.

The Baiterek effort involves building a launch pad — Zenit-M — that would ultimately be used for the Soyuz-5 rocket, and Kazakh companies signed up in a joint venture. Russia has reportedly spent around $900 million on the project, including the rocket itself.

But the project has dragged on, in large part because of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine and the sweeping Western sanctions that targeted important Roskosmos suppliers. A 2021 target for the first launch was pushed back to 2024, and the contract dispute has now left that in doubt.

Also complicating matters: a key supplier of Russian rocket components is based in Ukraine, which cut off all defense cooperation with Moscow after the invasion.

The dispute over Baiterek is focused mainly on whether Roskosmos’s main local subsidiary had violated its obligations by not completing a feasibility study on time.

A Kazakh court ruled it had, fined it $29 million, and ordered its local assets seized. Kazakh officials also say they’re reluctant to make a major investment in an already troubled project with a questionable outcome: why build a new launch pad for a new rocket when no one wants, or is able to, contract with Roskosmos?

“The final term for completing the Baiterek project will be determined after the adjustment of the feasibility study,” Kuat Mustafinov, the general director of the Kazakh partner in the joint venture, told the Kazakh news site InformBuro.

Aselkan, the magazine publisher, downplayed any political dimension to the dispute; the court fight isn’t an effort by Kazakhstan to push Russia out of Baikonur, he said.

But he added that Baiterek “is currently a suitcase without a handle.”

He predicted Roskosmos would continue launching people and cargo from Baikonur to the space station for the next five years.

‘Anything But A Reliable International Launch Source’

For observers of the space program, many of the woes Roskosmos is dealing with are self-inflicted.

Last year, just days before Roskosmos was set to launch the latest batch in scores of satellites for low-Earth Internet provider OneWeb, Rogozin made last-minute demands of OneWeb, including that the British government divest its stake. OneWeb refused and Roskosmos seized the satellites, which it still has not returned.

OneWeb declined to provide an on-the-record statement to RFE/RL.

Rogozin made some eyebrow-raising comments during his tenure as Roskosmos director, including suggesting that the man-made hole found in the Russian capsule was made deliberately by an American astronaut.

Rogozin also allowed three cosmonauts on the station to pose with the flags of separatist forces in eastern Ukraine, which drew an unusual public rebuke from NASA.

Days after that incident he was pushed out of his job, replaced with a more technocratic former deputy prime minister.

A NASA spokesman, meanwhile, told RFE/RL that the dispute at Baiterek was not related to the space station, saying that “there are no impacts to space station operations.”

Roskosmos did not respond to an e-mailed statement seeking comment.

“Before the invasion of Ukraine, there were signals of slipping quality controls, dealing with an aging workforce, and then there’s the funding challenges,” said Brian Weeden, a former U.S. Air Force officer who is now an expert at the Secure World Foundation, a U.S.-based think tank.

“Because of Ukraine, they’ve lost their international market and they’re having much harder access to get computer chips,” he said. “I don’t think everyone fully realized how much of an impact it had. Other countries scrambling to find other providers. It’s destroyed the trust in the Russian space program.”

“Even if they did have reliable equipment and capabilities, [the Russian government] behaved in a way that just made them an unreliable provider,” McClintock said. “And so they’ve closed the door on themselves as being anything but a reliable international launch source.”

With reporting by RFE/RL’s Kazakh Service and RFE/RL’s Russian Service

- Mike Eckel is a senior correspondent reporting on political and economic developments in Russia, Ukraine, and around the former Soviet Union, as well as news involving cybercrime and espionage. He’s reported on the ground on Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the wars in Chechnya and Georgia, and the 2004 Beslan hostage crisis, as well as the annexation of Crimea in 2014.