Lithuania Reinstates Conscription: Implications On Security, National Identity And Gender Roles – Analysis

By Published by the Foreign Policy Research Institute

By Agne Cepinskyte*

(FPRI) — In March 2015, the Lithuanian government reinstated conscription, which had previously been suspended in 2008. Each year between 3,000 and 3,500 men aged 19 to 26 years are to be enlisted in the military for nine months. Recently, the government has moved to increase the annual number of conscripts next year to between 3,500 and 4,000. The proposal, drafted by the Ministry of Defense, is likely to pass in the parliament. After all, in 2015, the majority of conscripts were volunteers. Over 2,000 volunteers have signed up this year, making the mandatory enlistment almost unnecessary. An opinion poll commissioned by the Ministry of Defense found that 68 percent of respondents support the reintroduction of conscription. 75 percent said they would approve if a close relative decided to join the military.

Political leaders, including President Dalia Grybauskaitė and Defense Minister Juozas Olekas, justified the reinstatement of conscription by the need to “enhance and accelerate army recruitment” given “the current geopolitical environment”. They were referring, of course, to Russia. The Russian-Ukrainian conflict, heightened tension between Russia and the West, Baltic airspace and maritime incursions by the Russian military, espionage incidents, and other provocations amplified fears that Lithuania could be the next target of the Kremlin. As a result, in the recent years, threats emanating from Russia have dominated the State Security Department’s annual reports on the “Assessment of Threats to National Security”. Lithuanians chose to take measures such as reintroducing conscription to send a signal to the Kremlin.

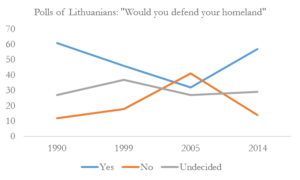

A recent opinion poll indicated that 55.5 percent of Lithuanians considered Russia a threat, while less than one-third believed it was not. Around the same time, a Lithuanian NGO Civil Society Institute published a study titled “Civic Empowerment Index”, which revealed that 57 percent would join the military forces in order to defend the country. This number was nearly double that of 2005, when Lithuanians felt safe after joining NATO and given relatively stable relations with Russia. Such findings show a correlation between the perceived threat to national security and the readiness to defend the country. Lithuanians are considerably more determined to join the armed forces during times of peril.

Military service and national identity

The importance of the perceived threat from Russia indicates that Lithuanians are generally not joining the military for pragmatic reasons such as a good salary, postponement of work or college, and social guarantees. Instead, they appear to be joining out of patriotism. Indeed, Lithuanian patriotism should not be underestimated. Throughout history it has played a significant role in state and nation building in Lithuania. It is an intrinsic part of the national identity. Furthermore, Lithuanian patriotism developed in resistance movements against the Russian Empire and Soviet Union. It is easily triggered by a renewed threat from Putin’s Russia today.

Volunteering to defend the homeland has historical resonance. One of the proudest episodes in Lithuania’s history is the partisan fight against Soviet Red Army and NKVD forces from the mid-1940s to the mid-1950s. Following the Soviet re-conquest of Lithuania in 1944, local partisans waged a guerrilla war against the Soviets to defend their homeland and attract Western attention. Together with Latvian and Estonian counterparts they were known as the “forest brothers”. The partisans established a joint resistance authority and organizational structure, printed newspapers, and ran training courses. They continued fighting the Soviets from their forest hideouts for a decade, with resistance petering out only after the “forest brothers” realized that, receiving no support from the West, their lonely struggle against the brutal Soviet machine was futile.

This active resistance ceased by the mid-1950s, coinciding with Stalin’s death and the loosening of repression. Yet the “forest brothers” became a symbol of Lithuanian patriotism, tenacity, and resilience. The highest-value banknote of the Lithuanian Litas (the national currency until 2015) was inscribed with the motto of a partisan newspaper: “Thou shalt ring through the centuries to the children of Lithuania: he who does not defend freedom is not worthy of it.”

Masculinity and the military

That Lithuanian men and women do not think twice when it comes to defending their freedom was clear in January 1991, when thousands of civilians poured into the streets to counter the military encroachment of the Soviet troops. However, the state imposes the obligation to serve the country on men only, while for women it remains voluntary. This rule itself is not unusual—Norway is the only NATO and European country to have draft women into the army. In Lithuania such a move is unlikely, because the public sees direct links between masculinity and military service. Anyone who tries to avoid military service risks being seen as insufficiently masculine. In 2015, only five enlisted men chose the alternative service, which is work of social value in state and municipal institutions.

The return of conscription sparked debate about gender roles. The speaker of the parliament Loreta Graužinienė argued that it was a man’s duty to protect the country, and women should focus on children and family. Two feminist activists, however, photographer Neringa Rekašiūtė and actress Beata Tiškevič, launched a photography project to challenge gender stereotypes. They photographed 14 teary-eyed conscripts to show that men can be emotional, and that masculinity did not imply the obligation to fight in a war. The project attracted much attention, though most Lithuanians did not receive the intended message. Instead, many people criticized the project for depicting soldiers as weeping cowards and worried that Russia would use this to portray Lithuanians as weak and defenseless.

Such fears did not take long to materialize. Russian news agency Regnum published an article titled “Potential ‘Defenders’ of Lithuania: We Weep, but We Are Men”. In a follow-up publication a year later the same agency claimed that Lithuanians were unpatriotic and the reinstatement of conscription was encouraging young people to flee the country. While these statements are false, attention from the Russian media shows that the Lithuanian government’s decision to return the conscription and the subsequent developments have been noted in Moscow. This helps explain the government’s proposal to increase the number of conscripts. Conscription plays a role in strengthening defense capabilities, but its symbolic value—demonstrating Lithuanian patriotism, self-confidence and courage—is equally important.

About the author:

*Agne Cepinskyte is a PhD candidate in Russian and Eurasian studies at King’s College London. Her research focuses on the issues of national minorities and security in the Baltic region. Agne holds MA degrees in International Law and International Peace and Security.

Source:

This article was published at FPRI