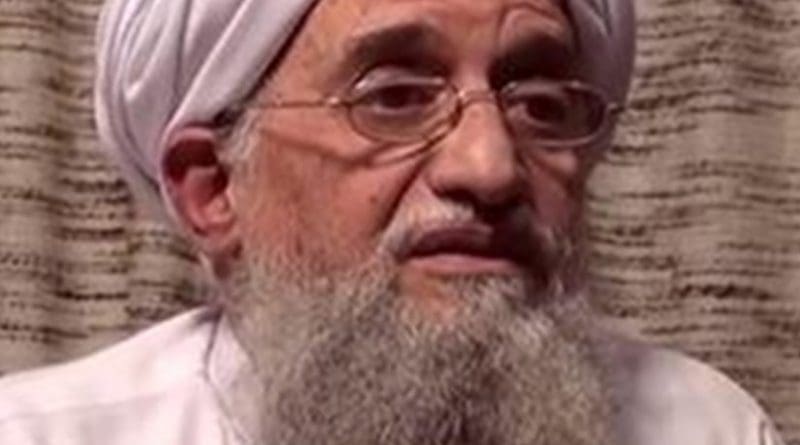

How To Read Al-Zawahiri’s Killing – Analysis

By IPCS

By Rajeshwari Krishnamurthy*

On 1 August 2022, the US announced that it had killed al Qaeda Chief Ayman al-Zawahiri in “a precise, tailored airstrike” on a safe house in Kabul. In his remarks, US President Joe Biden said al-Zawahiri had moved to downtown Kabul to “reunite” with members of his immediate family earlier this year; that “[n]one of his family members were hurt” in the airstrike; and that “there were no civilian casualties.” When and how his family moved to Kabul is unclear, as are details on whether relatives of Haqqani Network chief and Taliban-appointed Interior Minister, Sirajuddin Haqqani, had also been killed in this strike, as some observers have said.

Official US statements mentioned that “senior members” of the Haqqani Network in the Taliban structures were aware of al-Zawahiri’s presence in the city. Following the airstrike, they reportedly “acted quickly to remove Zawahiri’s wife, his daughter, and her children to another location.” Senior Taliban members stated the group was unaware of al-Zawahiri’s presence in Kabul, likely to project compliance with the February 2020 US-Taliban Doha Agreement, and called the US’ airstrike a violation of the Agreement. Later that month, the group even claimedthat al-Zawahiri’s body had not yet been found.

While the strike has prompted questions and speculation across the world, this episode also offers some clarity.

For instance, specifics about how the intelligence needed for such a strike was procured and verified, or the outcome of the strike confirmed, are not yet known. However, in a media briefing, an unnamed senior administration official said that the US had identified al-Zawahiri’s location by “layering multiple streams of intelligence,” building a pattern of life based on “multiple, independent sources of information,” and had been able to confirm the outcome of the strike based on such “intelligence sources and methods.”

The probability and identity of non-US involvement in this strike are among the topics that have dominated public discussion. Indeed, several actors had means, motive, and opportunity to ‘help out’. The Pakistan Army, armed anti-Taliban resistance groups in Afghanistan, Taliban members themselves, and even the Haqqani Network are among the top contenders. For example, citing logistical and other considerations, observers have highlighted the plausibility of Pakistan’s involvement. However, US officials have neither confirmed nor denied Pakistani involvement. The US also hasn’t specified where al-Zawahiri had relocated to Kabul from, although it is generally believed that he was living somewhere in Pakistan.

Meanwhile, the intensifying power struggle within the Taliban, involving a powerful Sirajuddin Haqqani, lends weight to the plausibility of Taliban involvement. Unconfirmed reports suggest the group is now cleaning house to find an internal informant, if any. Other reports that emerged shortly after the airstrike suggested that Haqqani had fled Kabul, with unconfirmed reports placing him in Khost province (where unknown drones had been hovering over that week), and across the border in Pakistan. Conversely, there are also some unconfirmed speculations that the Haqqani Network itself may have been involved.

Actionable intelligence, propitious timing, and the capabilities needed to execute a policy decision rarely converge. Even when they do, an optimal outcome is not necessarily guaranteed. This makes the case of al-Zawahiri’s killing particularly significant, especially given the circumstances under which it took place. These include reduced US presence in Afghanistan, logistical considerations of deploying a drone from ‘over the horizon’, and the risk-to-reward ratio of bombing a residential neighbourhood. In all such operations—but especially in one as important as this—logistics is a key lynchpin.

This incident demonstrates the US capability to strike even with reduced capabilities on the ground. It isn’t clear, however, if the strike fully reflects how much of the US’ ability to act has been preserved since its departure from Afghanistan. For instance, was this airstrike made possible by a one-time arrangement? Or does the US possess the on-ground capabilities to replicate this in the future, should it want to? These considerations notwithstanding, this episode can address some questions regarding the US’ diminished capabilities for action.

Irrespective of whether a Taliban insider was involved, it would be interesting to see if and what effect this has on two things. One, on the US-Taliban negotiations over Afghan Central Bank reserves that are currently frozen in the US. Two, on the US’ negotiating stance to improve the odds of getting the Taliban to meet its (and the world’s) demand of upholding women’s rights and instituting an inclusive political system in Afghanistan. How the US treats the US-Taliban Agreement going forward will shed some light. For instance, will the US feel freer to deviate from its Doha Agreement obligations, either for punitive purposes during negotiations with the Taliban (e.g., to incentivise the latter’s flexibility on the above-mentioned expectations) or for any other reason?

Be that as it may, the Taliban have been caught red-handed in violation of even the feebly drafted clauses of the US-Taliban Agreement. Under the Agreement, the Taliban hadn’t legally committed to severing ties with other terrorist outfits (including al Qaeda). They had only committed to “prevent any group or individual, including al-Qa’ida, from using the soil of Afghanistan to threaten the security of the United States and its allies” through specific measures outlined in Part Two of the Agreement. Nonetheless, the fact is that al-Zawahiri was killed in downtown Kabul in Taliban-run Afghanistan, in a house linked to the Taliban-appointed Interior Minister, Sirajuddin Haqqani—the very person responsible for preventing al-Zawahiri’s presence in the country, at least by virtue of his ‘portfolio’. Thus, vicariously or otherwise, the Taliban and its leadership are liable for al-Zawahiri being able to relocate to and live in Kabul.

In a way, al-Zawahiri being killed by a US airstrike right under the Taliban’s nose is reminiscent of what happened to his predecessor, Osama bin Laden, who was killed in a US raid in Abbottabad less than a mile from a Pakistani military establishment 11 years ago. Much like Pakistan’s quandary in the aftermath of the bin Laden raid, the Taliban leadership is faced with a Catch 22: as appearing either incompetent or deceitful.

Al-Zawahiri’s killing may just have catalysed a new dynamic in the country in at least two ways. One, the Taliban-Haqqani Network rift could widen just as easily as the intra-Taliban rift between absolute hard-liners and the more tactically-minded hard-liners. For instance, absolute hard-liners are completely opposed to reinstituting women’s rights and other civil liberties that were suspended after the group seized power in August 2021. The more tactically-minded hard-liners view resumption of women’s access to education as being a useful tool for making headway on international recognition of their administration. Two, the Taliban leadership (especially the Kandahari faction), which is already engaged in a power struggle with the Haqqani Network, is likely to hold Sirajuddin Haqqani responsible. The reasons for this include the damage Zawahiri’s discovery in a Haqqani-linked safehouse in Kabul does to the group’s already absent legitimacy (domestically and overseas), and by extension, its prospects for remaining in power.

On 27 July, three days before the airstrike in Kabul, a senior inter-agency US delegation held talks with the Taliban in Tashkent on the fate of Afghanistan’s Central Bank Reserves that are currently frozen in the US. The same day, four US Senators, including the chairman and ranking member of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, wrote to the UN Secretary General. They called on him and the UN Security Council (UNSC) to reimpose the travel ban on all Taliban leaders who were granted exemptions, to incentivise their participation in negotiations with the erstwhile Afghan government. There is precedent for this: of the 15 sanctioned Taliban leaders who had been granted exemptions, in June 2022, these were revoked for two (the Taliban’s de facto minister of higher education and de facto deputy minister of education) over the continuing ban on girls’ education.

On 4 August, three days after the airstrike and a day after US House Speaker, Nancy Pelosi, concluded her visit to Taiwan, the Taliban issued a statement calling for respect of national sovereignty and stressing “the pri[n]cipled one-China policy.” Perhaps this was the group’s way of hitting back indirectly, or an appeal for help from P5 member, China, or both, given that China held the presidency of the UNSC in August 2022. Indeed, when the scheduled review of the travel ban exemption took place on 20 August, views at the UNSC were split. China and Russia—both of whom have accepted Taliban-appointed diplomats in their countries—called for extending the exemptions. Nonetheless, the exemptions expired after other countries objected, and the US and some others called for restricting them further. How things unfold in Afghanistan will likely become clearer in the coming days as UNSC politicking over the travel ban exemptions evolve.

Rajeshwari Krishnamurthy is Visiting Fellow, IPCS.