Whatever Happened To EU’s Integrity With The Philippines? – Analysis

Recently, EU Parliament adopted a resolution denouncing the state of human rights and press freedom in the Philippines. However, the resolution seems to rely on flawed data, political agendas and prejudicial bias.

In Brussels, the resolution got 626 votes in favor, only seven against, and 52 abstentions. Nine of ten members of European Parliament (MEPs) voted for it.

Despite its stated concern for ordinary Filipinos, the resolution seems to reflect dubious cooperation between a small group of European parliamentarians and Philippine Liberal Party (LP) leaders who suffered a dramatic loss in 2016 – and who now seem to be positioning for the impending 2022 election.

But why would Brussels allow itself to be used in a way that risks European credibility?

PH drug explosion escalated under Aquino

The European resolution is based on estimates of Philippine extrajudicial killings and other human rights violations, which differ dramatically from the official figures. EU member states are pushing for an “independent international investigation” following Duterte’s presidency in 2016.

There may be a reason why the resolution is not keen to explore the magnitude of drug trade, corruption and human rights violations before 2016.

In the Philippines, Duterte’s government is the first that has taken the drug problem seriously, as do most Filipinos whose neighborhoods were invaded by drugs during the era of former President Benigno Aquino III (2010-16). That’s when drug syndicates began to produce meth, which caused illegal drug trade to soar to $8 billion.

US State Department had warned that drug trade and its funding could have a corruptive impact on Philippines politics. Yet, the drug problem was downplayed by Philippine media and largely ignored by international media.

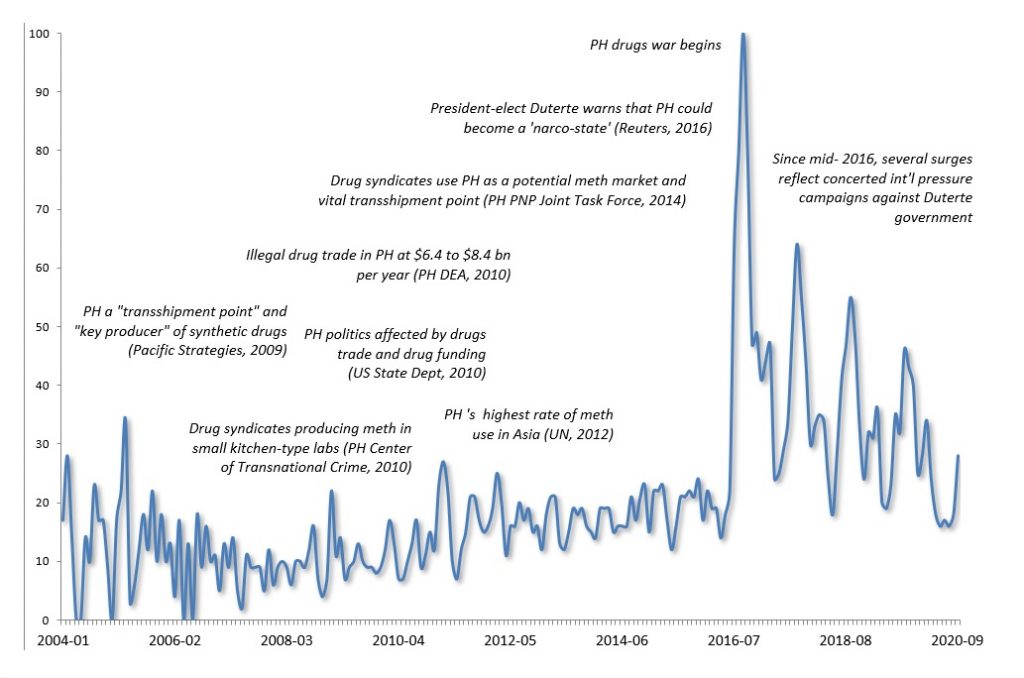

It was only after Duterte launched the war against the drugs that critics awoke, as Google Trend search evidences. Since 2016, there have been several surges, which reflect concerted, coordinated international pressure campaigns – but ones whose combined impact has progressively declined (Figure).

Figure Long silence about PH drugs until the Duterte Era*

The real question is where was the concerted international response when it was really needed prior to 2016?

Staggering costs of drugs and corruption

Before the 2016 election, the initial anticipation was that LP would win six more years with Manuel “Mar” Roxas as President Aquino’s designated successor. As the former interior minister and ex-investment banker in Wall Street, Roxas was seen as a sure bet. But Filipinos disagreed and Duterte won in a landslide victory.

Only days in the office, Duterte named half a dozen “narco-generals” believed to be protecting drug lords that allowed shabu (meth) sales to flourish during the Aquino era. Some were linked with Roxas who denied all ties with the so-called “Roxas generals.” Yet, some heavyweights, such as General Marcelo Garbo, the perceived “protector of drug syndicates,” had been identified among police generals in a closed-door meeting with Roxas’s staff at Manila’s Novotel Hotel.

Based on official data from June 2016 to July 2019, 135,000 anti-drug operations were conducted and 193,000 people were arrested. While 5,526 suspects died in 135,000 anti-drug police operations, over $720 billion worth of drugs were seized

LP leaders accused Duterte of inflating the drug problem, even though the number of addicts had reportedly soared to an estimated 4 million people.

According to independent international research, the cumulative value of illicit flows soared to more than $1 trillion in emerging Southeast Asia between 2003 and 2014. In country comparisons, the Philippines and Vietnam each lost over $90 billion in illicit financial flows during the period. Moreover, independent international data supports Duterte’s ‘narco-state’ concern. Between 2003 and 2013, Colombia lost “only” $15 billion in cumulative illicit flows, whereas the Philippines lost an estimated $75 billion more.

The question is why did the resolution ignore these cold realities of the drug trade and corruption that accelerated during President Aquino’s term? Without appropriate evidence, an exclusive focus on the opposition narrative fosters impression of prejudicial bias.

Why LP offshored its rights battles

During the ongoing drug war, the wide majority of Filipinos continue to support Duterte. As a result, the Liberal Party has effectively “offshored” the human rights accusations hoping to involve Washington and Brussels in an anti-Duterte crusade. That’s why the European resolution demands the Philippine government to drop all “politically motivated charges” against and the release of Senator Leila de Lima.

It is a demand that most Filipinos see as a travesty of justice. Already in 2016, Discovery Channel showed drug trade and gang leaders’ luxurious life in the New Bilibid Prisons, with the involvement of Senator de Lima who allegedly received millions of pesos in payola money from drug lords and had a 7-year affair with her lucratively-rewarded driver Ronnie Dayan – her money collector for drug protection and campaign finance.

Another role in the misrepresentations seems to belong to Chito Gascon, a veteran LP leader and the head of the Commission of Human Rights since 2015. As Gascon failed to garner adequate human rights support at home, pressure campaigns were taken to selected local and international media. What followed was a series of manufactured human rights “events” (the post-2016 surges in the Figure), often in cooperation with Vice President Leni Robredo.

Like de Lima, Robredo is amid a battle for her political life. After the 2016 election, former senator Ferdinand Marcos Jr. filed an election protest against Robredo at the Presidential Electoral Tribunal (PET), which has mysteriously kept the case pending for over four years, thanks to three Aquino-appointed justices, as disclosed by The Manila Times recently.

So, the question is, why would the MEPs allow EU’s association with a set of Philippine opposition politicians, whose activities seem to be motivated by political self-interest, moral hazard, or criminal conduct?

Not-so-independent media monies

The EU resolution decried the “threats, harassments, intimidation, unfair prosecutions, and violence” against journalists in the Philippines. It appealed to drop the case against Rappler CEO Maria Ressa and her former researcher; two journalists of the online news organization convicted of cyber libel last June.

To understand the consequent international pressure campaigns, it’s useful to follow the money. Last fall, Ressa was awarded by the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), which got wide international coverage. What was left unsaid was that the CPJ is funded by Pierre Omidyar, eBay’s controversial founder and Rappler’s billionaire funder. Right after Ressa’s arrest and release, the Omidyar Network and the CPJ raised $500,000 for her legal defense fund.

Despite murky financial flows and politics, Rappler portrays itself as an independent outfit. But as investigative journalists Alexander Rubinstein and Max Blumenthal have reported, “Rappler’s mission in the Philippines appears to have an ulterior and entirely opposite agenda.” The site’s user-tracking model has attracted concern because it couples journalism with behavior profiling.

Last mid-June, Ressa was found guilty of cyber libel. A week later, Hannah Neumann, the key MEP behind the European resolution, interviewed her in a public video streaming. Instead of measured balance, Neumann asked: “Maria, what can we do?” Apparently, Ressa persuaded her to push the EP resolution so that the Philippine government would withdraw all charges against her or risk European trade sanctions. In the process, Rappler’s violations of media legislation and murky financing flows were all conveniently ignored.

So, the question is, why would highly-regarded MEPs associate EU reputation with dubious political interests, controversial money flows and odd geopolitics?

Europe’s voice matters

The facts are clear. The drugs explosion in the Philippines preceded the Duterte years; it escalated under President Aquino. In the 2016 election, the drugs explosion contributed to LP’s meltdown. Such losses should lead to self-reflection and change. Instead, LP has relied on international pressure to restore a domestic status quo that most Filipinos reject. That’s one reason why President Duterte’s trust rating is now 91%, a historical record in the Philippines.

So, the question remains, why would the MEPs allow EU’s use for such partisan purposes. The European Philippine resolution appears to reward opposition leaders for their lack of integrity. Such actions undermine European credibility.

Today, European institutions – from the EU to European Chamber of Commerce – have a vital role in the Philippines. Europe’s role in the international arena is more critical than ever before. When Brussels acts without prejudice and bias, its voice will be heard and its pleas will be listened to. Unfortunately, the reverse applies as well.

Human rights matter and so does integrity.

For the original, longer version of this commentary, see The European Financial Review (October-November). This shorter version was released by The Manila Times on Oct 5, 2020

its not ABOUT BEING AGAINST DRUGS. We ALL ARE.

ITS ABOUT THE WAY TO FIGHT DRUGS.

its also abt with whom do you fight, the drug lords or mostly the drug addicts.

The numbers speak..more than any comment!