DoD Acknowledges Guantanamo’s ‘Forever Prisoner’ Is Case Of Mistaken Identity – OpEd

The Periodic Review Boards at Guantánamo began two years ago, to review the cases of all the prisoners not already approved for release (48 of the 107 men still held) or put forward for trials (just ten men), and last week I put together the first full annotated list, to assist anyone interested in the reviews to work out who has already has had their cases looked at and who is still awaiting a review.

The PRBs were set up in response to the conclusions reached by the high-level, inter-agency Guantánamo Review Task Force, which President Obama established shortly after taking office in 2009. The task force suggested that 46 men were “too dangerous to release,” even though they acknowledged that insufficient evidence existed to put them on trial, and President Obama promised periodic reviews of their cases when he approved their ongoing imprisonment without charge or trial in an executive order in March 2011. 25 others — initially recommended for prosecution, were later added to the list, after the basis for trial largely collapsed following a handful of devastating appeals court rulings. The mainstream media have helpfully labelled these men “forever prisoners,” but in reality assessing men as “too dangerous to release” is irresponsible, and not justified by a close examination of the facts.

Shamefully, although President Obama declared, in his March 2011 executive order, that, “For each detainee, an initial review shall commence as soon as possible but no later than 1 year from the date of this order,” we are now nearing the five-year mark, and yet just 20 prisoners have had their cases reviewed, and another 44 are waiting. Of those 20, 18 cases have been decided, and 15 men have been recommended for release, which is a success rate of 83%. This quite solidly demonstrates that the “too dangerous to release” tag was the hyperbolic result of an over-cautious approach to what purported to be the evidence against the men held at Guantánamo by the Guantánamo Review Task Force.

As I noted in the introduction to my list, however, “At the current rate … the PRBs will not be completed until 2020, ten years after the Guantánamo Review Task Force first made its recommendations. This is an unforgivable delay, under any circumstances, but even more so given that, through the PRBs, so many men are having their status revised from ‘forever prisoners’ to men approved for release.”

Much of the basis for the PRBs’ decisions — taken by panels consisting of representatives of the Departments of State, Defense, Justice and Homeland Security, as well as the office of the Director of National Intelligence and the Office of the Joint Chiefs of Staff — has involved risk mitigation, as it has become apparent that, in many cases, being regarded as “too dangerous to release” has actually meant being someone who is not regarded as sufficiently compliant or is perceived to have threatened or borne a grudge against their captors. Demonstrating a willingness to move on, and to make serious plans for life after Guantánamo has, as a result, helped many of the men to be approved for release.

However, it should not be forgotten that there are also huge problems with what purports to be the evidence against the men facing PRBs. In general the prisoners’ files, released by WikiLeaks in 2011, reveal all manner of untrustworthy allegations made by unreliable witnesses — men subjected to torture or other forms of abuse, or well-known liars who, in some cases, were rewarded with better living conditions, or, eventually, release from the prison. However, these lies and distortions are not generally acknowledged openly by the authorities.

Last week, however, a serious problem with the evidence became clear when the 20th prisoner, Mustafa al-Shamiri (aka al-Shamyri), had his case reviewed — and, I’m glad to note, media outlets that have generally ignored the PRBs ran stories focused on how he was a case of mistaken identity (see

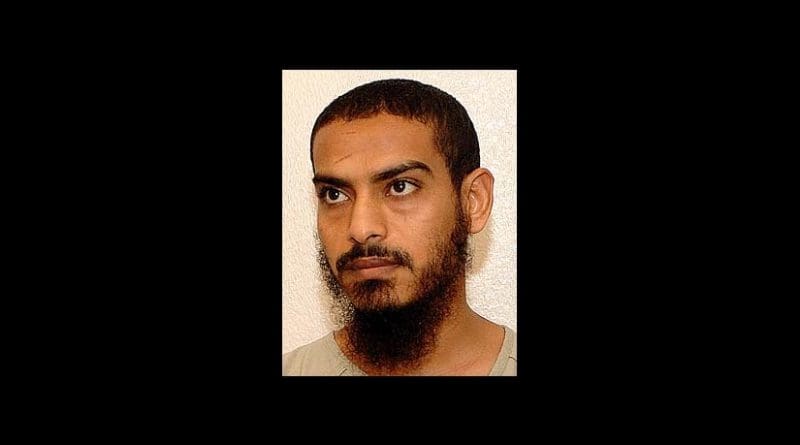

Mustafa al-Shamiri, the 20th prisoner to make his case before a Periodic Review Board

A 37-year old Yemeni, Mustafa al-Shamiri appears to have been nothing more than a simple foot solder, recruited via a fatwa in Yemen to go to Afghanistan to support the Taliban. However, in his “Detainee Profile,” made publicly available on the eve of his hearing last week, the Pentagon conceded that he was “previously assessed” as “an al-Qa’ida facilitator or courier, as well as a trainer, but we now judge that these activities were carried out by other known extremists with names or aliases similar to [his].” The profile added, “Further analysis of the reporting that supported past judgments that [al-Shamiri] was an al-Qa’ida facilitator, courier, or trainer has revealed inconsistent biographical, descriptive, or locational data that now leads us to assess that [he] did not hold any of these roles.”

This is not unusual, as the primary purpose of intelligence at Guantánamo appears to have been to try to ramp up the importance of those held, to justify their imprisonment, and to distract anyone from realizing the terrible truth — that the overwhelming majority of the men taken to Guantánamo were either innocent civilians or lowly foot soldiers.

As I explained when profiling al-Shamiri back in 2010, he “survived the Qala-i-Janghi massacre in November 2001, which followed the surrender of the northern city of Kunduz, when several hundred Taliban foot soldiers — and, it seems, a number of civilians — all of whom had been told that they would be allowed to return home if they surrendered, were taken to a fortress run by General Rashid Dostum of the Northern Alliance. Fearing that they were about to be killed, a number of the men started an uprising, which was suppressed by the Northern Alliance, acting with support from US and British Special Forces, and US bombers. Hundreds of the prisoners died, but around 80 survived being bombed and flooded in the basement of the fort, and around 50 of these men ended up at Guantánamo.” Most of those men have already been released.

As I also stated in 2010, identifying untrustworthy allegations at the time:

[Al-Shamiri] reportedly fought with the Taliban for ten months after answering a fatwa. One unidentified source claimed that he was “a trainer at al-Farouq,” and another allegation stated, implausibly, “Indications are that the detainee was a commander of troops at Tora Bora” (this was impossible, as he was captured before the battle of Tora Bora). One other allegation in particular — that “A detained al Qaida official identified [him] as a Yemeni national who participated in the Bosnian Jihad” — is unlikely, as he would have been only 15 or 16 years old at the time.

Al-Shamiri’s latest profile also reiterated another old claim, that “he may have been collocated at a safehouse in Yemen with operatives who plotted the USS Cole bombing [in 2000, when 17 US sailors were killed], although there are no other indications that he played a role in that operation.” However, this whole claim is deeply suspicious, as the man who made it, Humoud (or Humud) al-Jadani (ISN 230, released in 2007) is someone I have previously noted as a unreliable witness (see here for a another prisoner’s description of him as an “admitted liar,” see here for another prisoner, Hussein Almerfedi, refuting his claims, and see here for the D.C. Circuit Court explaining how it “did not rely on ISN-230’s statements because it found him incredible and wholly unreliable,” in an appeal in which Almerfedi also contended that “exculpatory evidence produced by the government to petitioner after [his habeas] hearing concluded,” relating to al-Jadani, “thoroughly undermine the credibility and reliability of ISN-230 because he was severely abused and mistreated at Guantánamo”).

In the rest of the “Detainee Profile,” the Pentagon noted that past reporting suggested that he “was supportive of fighting to protect other Muslims, but not of global jihad, and there are no indications that his views have changed.” He is also described as having been “largely compliant with the guard force,” although he has “mostly been uncooperative with interrogators, suggesting that he sees little value in either acting out or cooperating.”

Rather disturbingly, I thought, the fact that he has apparently “corresponded with former Guantánamo detainees,” is taken to indicate they they “would be well-placed to facilitate his reengagement in terrorism should he chose [sic] to return to jihad,” which indicates to me that the authorities consider the mere fact of corresponding with a former prisoner to have a sinister intent, although the profile’s authors at least added, “We have no reason to believe [al-Shamiri] has discussed terrorism, regional conflicts, or violence in general.” In addition, with a ban in place on returning any Yemenis to their home country, there is no chance that al-Shamiri could have his “his reengagement in terrorism” facilitated, even if it was not a far-fetched presumption.

In the Miami Herald, Carol Rosenberg noted that, at his hearing, al-Shamiri, who “appeared groomed and remarkably similar to a 2008 photo of him” in the file released by WikIleaks in 2011, was “seen seated silently in a chair with an oversized white T-shirt,”and “followed a script as an Army lieutenant colonel assigned to help him make his case said his family in Yemen’s capital Sana’a have lined up a wife for him, but did not specify where she lives. The Army officer also said that while Shamiri realizes he can’t go back to his tumultuous homeland, his family will provide ’emotional, spiritual or financial’ support wherever he is sent.”

Rosenberg was watching what she described as “a carefully scripted pre-approved ceremonial opening of the hearing,” which is all that the media are allowed to see. His military representatives — assigned to help him prepare for his hearing — spoke to the review board panel, who meet in a secure location in Virginia, by video link, and I’m posting their opening statement below. They noted that he was “earnestly preparing for his life after” Guantánamo, where he has studied English and art, and has also learned “carpentry and cooking,” which Carol Rosenberg described as “skills the prison has never acknowledged offering in its briefings on special classes taught by Pentagon paid contractors.” His representative also “said he had helped guards settle disputes as a block leader, and ‘does have remorse for choosing the wrong path early in life.’”

Periodic Review Board Initial Hearing, 01 Dec 2015

Mustafa Abd Al-Qawi Abd Al-Aziz Al-Shamiri, ISN 434

Personal Representative Opening Statement

Ladies and Gentlemen of the Board, we are the Personal Representatives for ISN 434. Thank you for the opportunity to present Mustafa Abd al-Qawi Abd al-Aziz al-Shamiri’s case.

From our initial encounter and all subsequent meetings, Mustafa has been very cooperative, enthusiastic, and supportive in the preparation for his Periodic Review Board. From the onset, he has demonstrated a consistent positive attitude towards life after GTMO. He has a strong desire to obtain an education in order to provide for a future spouse that his family has already located for him. In his approximate thirteen years at GTMO, Mustafa has been compliant receiving few disciplinary infractions. During his recent time as a block leader, he was regularly commended by the Officer in Charge for solving routine daily detainee issues.

Mustafa will show you today that he is not a continuing significant threat to the United States of America. He is earnestly preparing for his life after GTMO. During his time in detention, he has attended English and Art classes, in addition to acquiring carpentry and cooking skills. During the last feast, Mustafa generously took the time to prepare over thirty plates of pastries for his fellow detainees. When I asked him why he would make pastries for his fellow detainees, he said it’s because it makes him feel like he can give back and share with people.

Mustafa does have remorse for choosing the wrong path early in life. He has vocalized to us that while he cannot change the past, he would definitely have chosen a different path. He wants to make a life for himself. He is aware that Yemen is not an option and he is willing to go to any country that will accept him. As he has a large family that has been waiting for his release since his arrival in GTMO, where even the women work outside of the home, he will have family support wherever he is located whether it is emotional, spiritual, or financial. He is prepared to begin life outside of GTMO.

We are here to answer any questions you may have throughout this proceeding.