Death And Destruction On The Highways: A Global Disaster Hiding In Plain Sight – OpEd

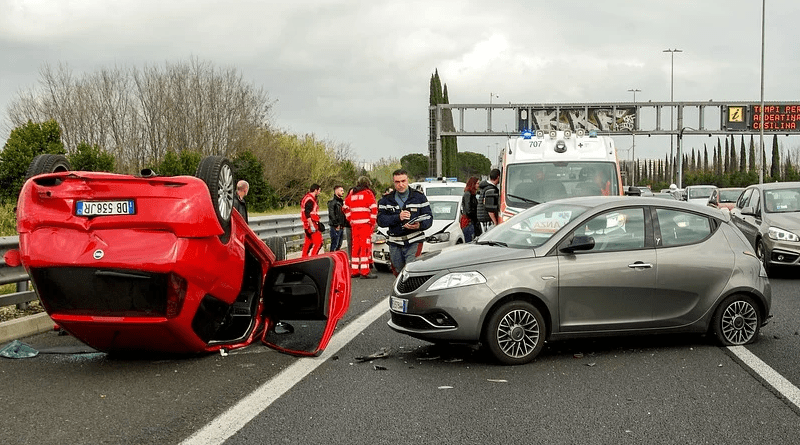

The statistics are spine-chilling, but also astonishing. In an average year in the current era, some 200,000 people worldwide can be expected to die in armed conflicts – far too many people, to be sure. In the same average year, 1.35 million people – about 3,700 per day — will die in road accidents. Since the ratio of deaths to non-fatal injuries in vehicle crashes is about 1:100, this means that more than 100 million of our fellow humans are maimed or injured each year in automobiles or other vehicles or as pedestrians.

The impact of this carnage on world society is devastating. According to the U.S. Center for Disease Control, traffic accidents are now the leading cause of death for young people around the world. The respected medical journal, The Lancet, estimates the annual cost of traffic deaths and injuries worldwide at $1.8 trillion – higher than the GNP of all but nine of the world’s richest nations. Furthermore, the burden of this mayhem on the road is not shared equally between rich and poor nations. The crash rate is more than three times higher in low-income countries than in those with high income, and the poorer nations bear the lion’s share of the costs of this destruction.

What is most surprising about this situation is the general lack of public consciousness and concern about it. Gun deaths, as we know, arouse passionate cries for gun control and passionate defenses of gun ownership. In the gun-happy U.S., annual deaths from shooting incidents now total more than 40,000. About the same number of North Americans die in traffic accidents, with 4.4 million injured, but there is virtually no public debate about this violence and very little collective action to remedy it.

In the U.S., the last popular movement to make automobile travel safer was that led by consumer advocate Ralph Nader in the 1960s. Since then, politicians and auto executives have proposed a variety of measures to lower rates of death and injury, ranging from mandatory seat belts and other car safety improvements to better methods of road construction and maintenance, but the results overall have been negligible. The U.S. still loses more people in traffic accidents each year than were killed in three years of the Korean War. In dollar terms, this destruction costs that nation as much each year as its entire military budget.

What accounts for the apparent indifference around the world to a calamitous loss of life and millions upon millions of serious injuries? Johan Galtung points to an answer in his famous 1969 essay on structural violence, “Violence, Peace, and Peace Research”[i]. There he notes that, unlike personal violence in which people intentionally and visibly injure each other, the violence generated by a social system can seem so natural and inevitable that it virtually disappears from people’s consciousness. Consider the horrific physical, psychological, and developmental damage caused by the system of chattel slavery in the United States. For centuries, this was thought of (if at all) as the inevitable “collateral damage” produced by a flourishing economy that employed millions of people in agriculture, clothing manufacture, shipping, finance, and subsidiary enterprises and that produced cotton, the nation’s primary source of foreign exchange. The protests of a relative handful of abolitionists were largely ignored by those who considered Black people unfit for freedom or who feared the social and economic upheaval that a change of system would entail.

In the case of traffic deaths and injuries, the system that generates damage is the automotive industrial bloc: four conjoined industries that have created the modern system of private auto transportation. The automotive industry manufactures, retails, and repairs cars, trucks, motorcycles, and other vehicles. The energy industry produces, transports, and sells oil, gas, and automotive fuels. Road construction enterprises build and maintain roads, bridges, and highways. And financial institutions engage in banking, trading in securities, and other activities designed to finance these industries.

One should probably add to this list the lawyers, police officers, and public officials at all levels of government who make and enforce rules designed to secure the health of the bloc and to placate its critics without making fundamental changes in its structure. Estimates of the percentage of the workforce employed by these industries or the size of investments in them are unreliable, but their activities clearly account for a substantial chunk of most nations’ GDP.

As in the case of slavery, many people cannot imagine an alternative system that will not create a vast socioeconomic upheaval and endanger their individual freedom.

Interestingly, if one talks to people about the causes of death and destruction on the highways, few are inclined to hold the automotive bloc responsible for this result. Instead, one hears a great deal about irresponsible drivers who drink and drive, text and drive, or simply drive too fast for their own good. Occasionally, automobile companies are blamed for manufacturing defects. But the habit of saddling immoral or negligent individuals with responsibility for a system’s failings is par for the course. Many observers blame sadistic prison guards and violent inmates for violence in the prisons, just as they held sadistic slave owners or rebellious slaves responsible for the violence of chattel slavery. In all these cases, attributing the damage to individuals makes it seem either that there is no system at all – just individuals doing what they do – or that the system is essentially beneficent and is only destructive on the margins.

It is necessary, therefore, to state the obvious. A system of capitalist enterprise that generates profits for a major industrial bloc is responsible for killing and maiming millions of our human brothers and sisters each year. Moreover, this economic system is supported by cultural and political norms, ideas, and feelings that make it difficult to imagine a practical alternative. In many nations, for example, the private ownership of automobiles is associated with personal freedom and any restrictions on that freedom – for example, the creation of auto-free urban zones – may be considered intolerable. In others (particularly poorer nations or communities), the auto is associated with upwardly mobility, and owning one becomes part of one’s dream of success. Almost everywhere, people are taught to consider driving an expression of their individuality and a pleasure, even while overcrowded highways have made commuting to work or other travel in highly populated areas as boring and dangerous as military service.

As time goes on, people do become aware of the gap between promise and reality. One response has been a movement to increase the availability of means of public transport such as buses and commuter trains. In wealthier societies like those of Western Europe, public transportation can be pleasant, efficient, and safe. This is one reason that the automotive death rate in Europe is approximately 9 out of 100,000 people, whereas In Africa, Asia, and Latin America the death rate reaches 24 per 100,000. Public transport systems in the poorer nations tend to be underfunded and underdeveloped, which gives their inhabitants even less reason to imagine a system that could get people where they wanted to go without slaughtering thousands on the highways. Even in Europe, however, public transport is considered a supplement to the system of privately owned vehicles rather than a replacement of it, with the result that approximately 23,000 Europeans are killed each year, with more than one million injured seriously enough to be hospitalized. In recent years, the “driverless car” has also been promoted as a possible solution to the problem, but how such autos will be gotten into the hands of low- or middle-income citizens, and how these drivers will be persuaded to give up their “right” to do their own driving, are unanswered questions.

It seems clear that to end the current reign of terror on the highways, the current transportation system dominated by the automotive industrial bloc, and the ideas and feelings that support that system, need to be rethought and refashioned. Those interested in peacebuilding and conflict resolution should include this long-range project in their thinking and practice. Part of our mission is to make the “invisible” or “inevitable” violence generated by destructive systems visible, and to help our fellow humans imagine and implement methods of ending this violence. This means encouraging interested parties to imagine alternative systems and facilitating discussions aimed at realizing these changes nonviolently.

The prerequisite to all this, however, is a perspective that permits and encourages outrage and sadness at the unnecessary loss of life and limb, and the psychic damage done to motorists and their families, as a regular product of the current system. There will come a time, I believe, when people will ask, as they now ask when thinking about slavery, “How could reasonable people have tolerated this violence?” In the future – perhaps sooner than we think – ruining millions of lives on the highway in the pursuit of automotive profits will seem as savage and as avoidable as the depredations of chattel slavery.

NOTE:

[i] Journal of Peace Research, Vol. 6, No. 3 (1969), pp. 167-191

*Richard E. Rubenstein is a member of the TRANSCEND Network for Peace Development Environment and a professor of conflict resolution and public affairs at George Mason University’s Jimmy and Rosalyn Carter Center for Peace and Conflict Resolution. A graduate of Harvard College, Oxford University (Rhodes Scholar), and Harvard Law School, Rubenstein is the author of nine books on analyzing and resolving violent social conflicts. His most recent book is Resolving Structural Conflicts: How Violent Systems Can Be Transformed (Routledge, 2017).

This article originally appeared on Transcend Media Service (TMS)

“”and how these drivers will be persuaded to give up their “right” to do their own driving, are unanswered questions.””

I think that the concept of “rights” is an absolute-ist idea – not internally compatible within a large and varied society.

It should be replaced with a system of privileges and permissions which can be removed if abused