From Essence To Black Girl Magic: History Of Black Women’s Image In Media

As a child, Timeka Tounsel spent hours flipping through the pages of Essence magazine in a Detroit beauty salon. The magazines, she remembers, were filled with images of and content tailored for Black women, offering something many other forms of mass media at the time did not: representation.

These memories inspired Tounsel, now an assistant professor of African American studies and media studies at Penn State, to write a new book exploring how mainstream brands and mass media companies have represented — and profited from — Black women throughout the years.

“There have been many periods of time in which Black women are celebrated in the media, such as in Essence when it originated in the seventies and today with many companies talking about ‘Black Girl Magic’ and being anti-racist,” Tounsel said. “But while this content can certainly be comforting and affirming, it also comes with a strategy and commercial agenda from the point of view of the companies.”

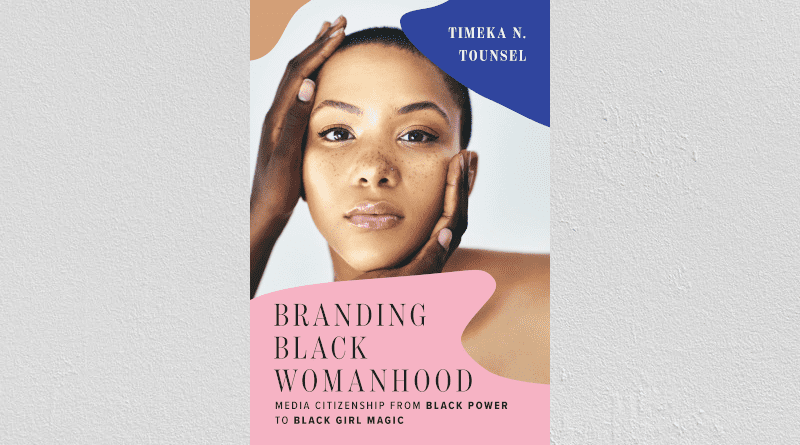

The book — “Branding Black Womanhood: Media Citizenship from Black Power to Black Girl Magic” — is available now from Rutgers University Press.

Using images to affirm and profit

According to Tounsel, the book started as a project detailing the cultural history of Essence magazine: how it began, the gap it was filling in the media landscape, and the kind of publication it eventually evolved into. But as she continued her research, Tounsel said she kept wanting to make connections to the contemporary moment, which she refers to as the “era of Black Girl Magic.”

The phrase “Black Girls are Magic” — later shortened to the hashtag #BlackGirlMagic on social media — was coined by CaShawn Thompson in 2013 as a way to celebrate and uplift Black women. However, Tounsel said the phrase was eventually co-opted by companies as a way to attract and market to Black women customers.

Tounsel said one of the things she wanted to communicate was that despite the buzz seen on some companies’ advertising and social media campaigns — and despite representation in the mass media certainly being important — the intentions behind this content can be blurry.

“Black women being more visible or lauded in the media, especially in advertising, doesn’t mean that Black women as a group within the U.S. are actually more powerful politically,” Tounsel said. “This moment we’re experiencing now is not the first time we’ve experienced it. Usually there will be a moment of intense focus on a marginalized group, but then it will fade. And whatever change comes about tends to be some, there aren’t big structural changes.”

Throughout the book, Tounsel discusses the history of Black women’s “image economy,” which Tounsel defines as representations of Black women within the commercial sphere, including magazines, TV, film and ads.

“The ‘economy’ part is important, because I wanted to underline the fact that these representations are always attached to a commercial motive,” Tounsel said. “Essence is thought of as this legendary Black institution because it dared to really speak to and represent Black women when most other women’s magazines did not. But it was a business. The people who founded Essence didn’t do it out of the kindness of their heart, they did it because it was a way for them to become wealthy.”

Image economy over time

The book is organized into four sections. The first explores the image of the “new” Black woman created by the male executives of Essence – and how this image was further shaped by the future women editors of the magazine. The second chapter discusses the tenure of Susan L. Taylor, Essence’s editor-in-chief from 1981 to 2000.

Chapter three moves into the 21st century, where Black women had been established as a consumer group and corporate brands had started using affirmative messages as a marketing strategy, according to Tounsel.

“With a focus on Proctor & Gamble’s ‘My Black is Beautiful’ and Ford Motor Company’s ‘Built Ford Proud,’” Tounsel wrote, “I probe what these multi-platform product marketing initiatives signify about Black women and who they benefit.”

In the final chapter, Tounsel discusses how Black creators like Issa Rae — who wrote and starred in the TV show “Insecure” — and Lena Waithe, creator of the show “Twenties,” have used vulnerability in their work to portray Black women as complex human beings.

It’s important, Tounsel said, to avoid representation that is too idealized, and that there may actually be negative consequences to putting Black women on a “superhuman” pedestal. For example, institutions in which Black women are traditionally underserved may think they can continue to underserve Black women, because they’re expecting them to be resilient and strong.

“Instead,” Tounsel said, “it would be better if Black women were just recognized as being human, and all of the things that come along with humanness.”