Watchdog Or Lapdog: The Media In Twenty Years Of Democracy – Book Review

By Kola King

The Nigerian media, especially the press, has its roots in the anti-colonial struggle for self-government and independence. The press was at the barricades during that era leading the way and showing the light to the people. It’s not for nothing that foremost journalists like Dr. Nnamdi Azikiwe, Mr. Ernest Ikoli, and Chief Obafemi Awolowo, among others, were among the great nationalists and arrowheads of the independence movement. Back then, the press was in the thick of that epic struggle for independence. In short, independence was won through the instrumentality of the press.

Today, the press is generally regarded as the fourth estate of the realm. To write about the press connotes writing in generic terms for the mass media. They have become the arbiter of a national conversation, setting the agenda for the government and the people. The press has transited through different phases in the life of the nation. After winning independence, the press was at its best serving as the watchdog of the people, holding the new leadership to account. Again it played a heroic opposition role during the military era as the vanguard of the oppressed and the tribune of the people. Once more, it rose in stout defence of the people as a crusader for the return to civil rule.

Since the return to civil rule in 1999, the press has become more ambivalent, parochial, and partisan. Some sections of the press seem to have taken a vow of silence and sycophancy. It appears as if the media have become co-opted partners or compromised lapdogs. Despite the diversity of ownership in the media, still, it serves more as an instrument for the contestation of power and ideas. For instance, Section 22 of the 1999 constitution enjoins the media to “monitor governance and to uphold the responsibility and accountability of the governed to the people.” But whether the press has been able to live up to the billing is another thing altogether.

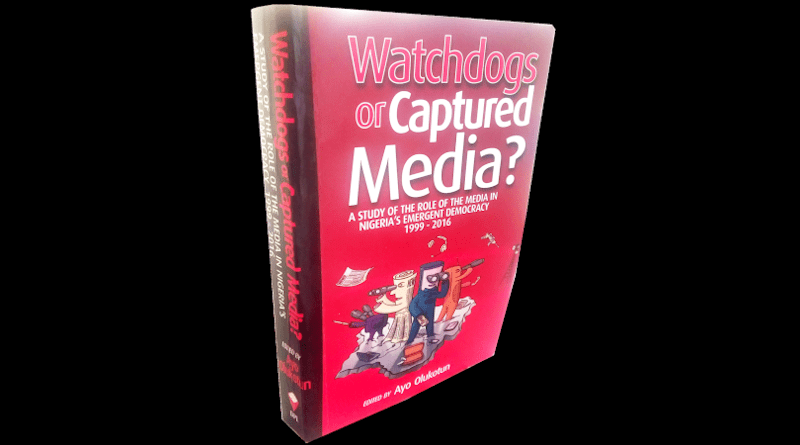

According to a primer titled “Watchdog or Captured Media: A Study of the Role of the Media in Nigeria’s Emergent Democracy 1999-2016” edited by Ayo Olukotun, the media has enjoyed more freedom in the current dispensation and this has been deepened by the passage of Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) 2011. The book consists of 13 chapters on various aspects of the media in the fourth republic ably handled by both experts and practitioners in the field of communication and cognate disciplines. In a word, this book provides a prism through which we can assess the press in the preceding years of democracy.

In general, the authors note the role, changing profile, record, and context of activities of the Nigerian media in the intervening period. However, there are fears that the media have been captured by entrenched interests, that is, both the political class and business class, and have therefore lost its bite. For instance, Ayo Olukotun in his contribution to the primer observes that broadcasting is still hampered because granting of license is a presidential prerogative. A major challenge of broadcasting is the high license fee which restricts ownership and a restrictive clause in the broadcasting code which limits editorial content and programming. By every token, newspapers, on their part, have a tradition of lively outspokenness partly because it is private sector-led and because of the history of civil agitation from colonial rule, and because religion and ethnic diversities make dictatorship hard.

Furthermore, Olukotun notes that media as the watchdog of democratic liberties is entrenched in liberal, social, and socialist democracies. Its forte includes muckraking, investigative journalism, exposure of scandals and corruption in high places, and vigilance on the conduct of public officials which is the bedrock of democracies. The capacity of the media to fulfill its watchdog role is founded on historical antecedents, media ownership and structure, changing technologies, production modes, and governance structure as well as shifting perceptions of audiences who consume media products.

By his assessment, the watchdog role has not been as effective as before due to increasing cases of media corruption which has become more prevalent. Yet Olukotun acknowledges the role played by the press in resisting the third-term agenda of former President Olusegun Obasanjo as well as its anti-corruption crusades.

Olukotun also looks at changing economy, technology, and ownership landscape within the context of high mortality rate, protracted default of the salaries of journalists, the emergence of a partisan journalistic sphere with the establishment of media by politicians. Against this background, the watchdog role of the media has been thrown overboard because of limitation of capacity, and harsh constraints of an economic milieu hostile to business. Thus at the moment critical and investigative journalism cannot be sustained as a media agenda.

In his contribution, Prof Chris Ogbondah observes that the period under review was marked by preemptory arrests, persecution of critical media, and forcible closure of some newspapers. Prof Ogbondah supports the view that the media is caught between a failing state and a deformed public sphere, and suffers from an information deficit. He argues that the media has been bifurcated into ethnic, religious, and regional enclaves. Hence one social crusader is another ethnic irredentist. Moreover, the fragility of the media is witnessed by its economic and technology profile and mortality rate among the newspapers.

On their part, Prof Lai Osho and Dr Tunde Akanni in a paper titled “Democracy and the Digital Public Sphere” narrate the development of electronic journalism and the growth of online platforms. The authors note the increasing use of social media platforms such as Twitter and Facebook by government officials, the development of online journals, and citizen journalism. They argue that online journalism has revived investigative journalism and liberalized access to the public sphere. It is generally agreed that online news media have made a robust contribution to the growth of the media.

In his contribution, Lanre Idowu writes that despite flashes of brilliance, the media continues to manifest unethical behaviour and corruption which is partly a reflection of the decay in the larger society. Idowu argues that corruption within the mainstream media requires systemic, multi-pronged long-term struggles. He suggests upgrading skills in media management, naming, and shaming mechanisms to discourage unethical behaviour and enforcement of journalistic codes. He also draws attention to the Code of Ethics for Nigerian journalists 1998 which expressly decries corruption under Article (7) (1) on reward and gratification. For him, corruption damages media credibility since it corrodes the notion of public service and compromises standards.

On the face of it, the media can beat its chest with pride and boast that FOIA has been one of the biggest gains of democracy. Yet the FOIA has been observed more in the breach as all manner of obstacles are placed on the path of the media in its bid to access information. Still, Edetaen Ojo notes the decade-long struggle by journalists and civil society actors to ensure the passage of the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) bill into law. The struggle started in 1999. Yet the bill was only passed into law in May 28, 2011.

Once again, Prof Chris Ogbondah asserts that in spite of formal structures of democratic rule since 1999, there are continuities between the military years when the media struggled against a tight leash and period of democracy. Some repressive laws have been removed. The FOIA empowers journalists and civil societies in their struggles for accountability. Yet there remain many more miles to be covered in search of a free press. He notes that despite democracy, there is repeated media closure, confiscation of publications, threats, physical assaults and killings, use of criminal libel, and seditious suits against journalists. He observes that the press operates under a better climate now, but now and then, we find reversion to the years of impunity and outright persecution.

Yet again, the writer identifies obstacles to media freedom which include antiquated laws yet to be expunged from the statute books such as the Official Secrets Acts of 1962, a child of the colonial era which describes all government-held information as ‘Top Secret.’

Besides, there have been conflicting rulings on the application of FOIA. Again, extra-legal action such as the use of arbitrary actions and extra-legal measures by the State in relation to journalists has been a common trend. From the onset of democracy in 1999, the Department of State Security Service (DSS) has arrested and detained scores of journalists despite the fact that several obnoxious laws hampering free speech have been expunged from the statute books.

Moreover, criminal libel and seditious suits have been used to intimidate, harass and discourage journalists from criticizing the government. For example, Imo Eze, director Ebonyi Voice newspaper, and reporter Oluwole Eleyinmi were charged with sedition in 2006. In the same vein, the Akwa Ibom government brought similar charges against Jerome Imeime a newspaper publisher in that state. He was charged with libel for an article that accused former governor Godswill Akpabio of corruption. In 2014, Ebere Wabara a journalist with the Sun was charged with seditious publication against former governor Theodore Orji of Abia State.

As it happens, apart from external threats to the survival of the media, there are internal problems the media are grappling with. It is common knowledge that many media organisations are in the doldrums, in terms of their financials. This explains why despite the fact of liberalization of the broadcast media, and the issuance of 402 licenses by NBC, many are yet to go on air because of financial constraints.

On a related note, the print media is hard hit by the prevailing economic situation. Several newspapers have been shut down during the period under review. Still, there are both external and internal threats to the survival of the media. There’s rampant unethical behaviour among journalists. The broadcast media and to some extent the press have been fingered in the publication and broadcast of fake news. Based on empirical evidence there’s a general tendency to write based on ethnic consideration in news reporting and partisan coverage of scandals. This has been more prevalent in the intervening period.

Whatever may be the misgivings about the unethical behaviour of the media, external factors bordering on excesses of security agents as well as sundry internal contradictions inherent in media operations, twenty years of democracy has been a rollercoaster ride for the media. There have been many highs and lows. Yet democracy offers the media a platinum opportunity to reinvent itself and align with its avowed constitutional duty of being a watchdog for society. Despite its shortcomings, many applaud the media for its role in the political and democratic process.