Media Ethics In Professional Journalism: Serving The Truth Or Un-Truth – Essay

By Prof. Dr. Sabahudin Hadzialic

Machiavellians selfishness & Public service Kautilyans

Morality is a multi-sided thing – a state of character that derives from rationalism and mysticism, from personal and social concern, and from habitual, virtuous acts based on a concern for consequences. And/or pre-determined principle. It is part rational and part emotional. It is part deterministic and part instinctive. It is part egoistic and part social. It is part secular and part religious. Being ethical, then, is theoretically relative.

There are communicators, Machiavellians in heart, who enthrone pragmatism and care little for humanistic ethics. They have a selfish motivation. Something that works is better than something that doesn’t. Results dominate over principle. Other Machiavellians of a different kind are among mass communicators. They may be called Kautilyans, wanting to use any means necessary to achieve an altruistic end. In India, at least five centuries before Machiavelli, a political adviser Kautilya mixed pragmatism with a compassion for the poor, for woman and slaves.

As with Kautilya, American pragmatic philosopher John Dewey, would stress the collective good. He would see individual journalists as submerging their personal desires to benefit the group or community.

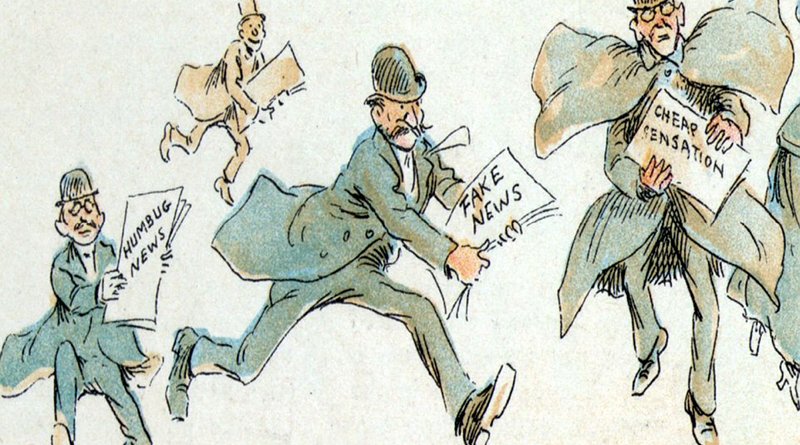

Today we have the public-service Kautilyans and the egocentric Machiavellians. It seems that all journalists are to some degree Machiavellians of one or both types, thriving on the scoop and the big story regardless of how they manage to get it – to give them personal or institutional prestige or to serve some segment of the public.

At the base of most communication ethics, in the Western world at least, is the concept of truth. But, for many, truth can be dangerous, and not only that, it can be “unethical” in some cases. But it persists as a foundation stone of ethics.

Half-truth, distortions, and outright censorship dominate in the media world. And this is not surprising, so the postmodernists who believe that there is no truth – or any truth is as good as any other truth. Just to remind you on any war that is going on the planet – everybody is saying GOD IS ON OUR SIDE – So, the funny question is really, why the God is not only on proper, honest, balanced and truthful side, and he is on all sides, as we can see?

So, the “truth” is communication is the truth that is created by encoders, refined by communicators and formed by audiences (decoders). Behind this communicated truth may be the “real” world, but our communicators and audiences will never see it. And it may be a good thing they don’t. It would be too much for the person to bear – seeing the real world in all its detail would send humanity into a psychotic tailspin.

Ethical nihilists & Existential journalism

The consideration of the purpose of the media varies from medium to medium, from society to society. But we can assume that media want to inform, entertain and interpret. The entertaining purpose offers the greatest ethical danger.

But information, too, is problematic, due to the nature of the information and its gathering. As for interpretation, a medium may well persuade, steer their audiences in certain directions, not all of them helpful. The ethical assumption is that media will be honest, fair, balanced and truthful in their efforts – but we know that such and assumption is generally unrealistic, yet.

The pragmatic assumption, a more realistic one, is that media will serve their owners and interests, provide a propaganda outlet for some special elite, or do what is necessary to survive, or serve the public interest. It is possible that the media can do all four above mentioned efforts, but it is doubtful. If we talk about media in North Korea, we have different expectations than of we are talking about media in USA. Media ideology stemming from political realities of a society affects ethical perspectives and, to a large degree, determines media freedom and purpose.

Walter Lippmann and others have pointed out that press freedom rests on the assumption that the media will provide serious material that will permit the citizens to be wise and well-informed voters. It is not freedom to do anything. The person concerned with media morality would tend to agree with Lippmann, but the problem is the determination of what is socially an politically helpful and what is not.

After looking at ethical codes around the world, it is fair to say that the most common ethical imperative seems to be truth-telling. Truth, of course, means many things to different media.

One ethics scholar has written that journalists who falsify, embellish and plagiarize their stories are guided by a philosophic framework called “ethical egoism”. I, as John Merrill as well, disagree with this. Such a journalist does not have anything with ethics whatsoever. An ethical egoist is one who strives to be ethical according to his or her own drive to do the right things. The falsifying and plagiarizing journalist is not trying to be ethical. We should call the unethical journalist by the proper label – unethical. Or maybe “ethical nihilist”.

On other side, closely related to individualism, in fact perhaps an extreme form of it, is what has been called existential journalism. The existentialist would also enthrone responsibility – but personal responsibility. Who knows, maybe existentialist stance might be just the answer we need. Perhaps it is only individual communicator, acting authentically and progressively, that can make impact. Now with the new media added to the old and personalized verbal interaction becoming important, freedom – the quiddity or essentiality of existentialism – has become increasingly possible.

Question to think about: Is the truth ethical or non-ethical issue when it comes to every day pragmatic world of journalism?

Next: Media ethics in professional journalism: To inform, entertain and interpret