Learning More Than Ever, Faster Than Ever, About What We Breathe

Nobody is currently taking continuous, routine measurements of the particles suspended in America’s air, called aerosols. That is set to change as a new, nationwide monitoring network launches with a site in Riverside, California.

When American scientists want information about the aerosols, they have to collect samples and ship them to a laboratory for analysis. The samples are typically collected every three to five days, which is suboptimal for understanding air quality events that happen more frequently.

“You want a real-time look at what’s happening, not a piecemeal puzzle picture,” said Roya Bahreini, UCR professor of atmospheric science and co-leader of the monitoring project.

Airborne particles can affect the climate, Earth’s ecosystems, and human health. Without understanding their nature — what they are, how often they appear, where they come from, their quantity and origin — efforts to mitigate them aren’t as effective.

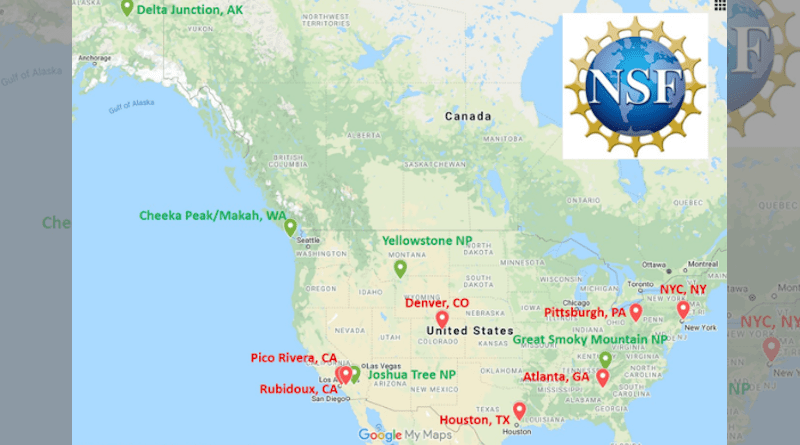

For these reasons, the National Science Foundation has granted $12 million for the next three years to the Atmospheric Science and mEasurement NeTwork, or ASCENT project, whose principal investigator is Nga-Lee “Sally” Ng, chemical engineering professor at the Georgia Institute of Technology. The network establishes state-of-the-art aerosol monitoring at 12 sites in the U.S., spread among urban and remote environments. Three of the sites are in Southern California.

Locally, Bahreini is overseeing the installation of new monitoring equipment at the South Coast Air Quality Management District’s Rubidoux monitoring site in Riverside, a good spot for gathering data about particulate matter that floats inland from the Los Angeles metro area.

Data collected at Rubidoux, along with data from Pico Rivera and Joshua Tree National Park, will allow scientists to investigate changes in aerosol properties as they are transported away.

“We know air flows bring pollution inland,” Bahreini said. “That’s why we believe this spot will be interesting for epidemiologists who want to see how this aged air pollution is impacting the health of local people.”

With the increase in Southern California wildfires, phone apps that offer air quality information have seen a surge in popularity. However, Bahreini explains that those services offer an idea of the total concentration of aerosols, rather than specifically what they are made of, their size, or their age.

Some instruments being installed at Rubidoux will offer data about the airborne amounts of sulfate, ammonium, nitrates, chloride, trace metals, and soot, or black carbon. Others will measure the size distribution of various aerosols.

Differently sized aerosols can have different impacts on our health. In addition, size can indicate something about the way the particles are formed.

“Larger-sized particles have been in the atmosphere for a while and accumulated components from other aerosols or condensable gases,” Bahreini said. “If we’re comparing aerosols in Pico Rivera to those in Riverside, we want to know their size. If they’ve grown, what has led to this growth?”

To make the data as widely available as possible, Bahreini will help train officials from the South Coast Air Quality Management District in the use of the new instruments, and a website with the real-time data from all the sites will be publicly accessible.

Ultimately, Bahreini hopes that the ASCENT partnership and establishment of a national aerosol monitoring infrastructure will open pathways for future research by atmospheric chemistry and climate scientists, air quality modelers, and epidemiologists.

“We are much more likely to be able to control what we can understand,” she said. “Data from this network will help us truly understand the influence of infrequent events on our air quality. Long-term trends in the data are also critical for formulating new policies to better protect human health and the climate.”