Violent Radicalization Revisited: A Practice-Oriented Model – Analysis

By Daniel Koehler*

In the two years following the July 2005 attacks in London the term ‘radicalization’ entered the mainstream lexicon. Rarely used at all before 9/11, the term is now widely used to describe a process of individual evolution towards adopting certain ideas and sometimes the use of violence and terrorist tactics to achieve political goals. To what extent the use of violence is a necessary component of radicalization is highly debated among scholars and policy makers, which is why the differentiation between“violent” and “non-violent” radicalization has become common. In general, radicalization describes cognitive and behavioural components that may lead to a destructive or violent outcome. But only rarely have the mechanisms behind radicalization been described in a step by step process. As a result, practitioners and policy-makers generally lack a coherent understanding of what exactly happens during radicalization processes and why they can be so dangerous to societies. Indeed, it is not enough to say that “violent radicalization” is the process that turns individuals into terrorists or extremists. Instead, violent radicalization must be understood more precisely: as a process of ‘de-pluralization’ within an ideological framework that is incompatible with mainstream political culture and ideology.

Radicalization as de-pluralization

Given the need for a sharper conceptualization of the process, radicalization can be understood as a process of individual de-pluralization in terms of political concepts and values (e.g. justice, freedom, honour, violence, democracy). The more individuals have internalized the notion that no other alternative interpretations of their (prioritized) political concepts exist (or are relevant), the more we can speak of (and show) a degree of radicalization. This may happen with varying degrees of intellectual reflection, such as quoting a fascist thinker to explain behaviour or merely stating an intention to do something based on a certain cognitive framework or collective identity. This means, however, that a high level of radicalization does not necessarily imply a high level of violent behaviour or brutality. Radicalization in this sense is a normal social phenomenon — seen, for example, in sports, political movements or dietary preferences. Radicalization becomes problematic, however, when it is combined with ideologies that inherently deny individual freedom (or equal rights) to persons not part of the radical person’s in-group or that are otherwise ideologically incompatible with the surrounding mainstream political culture or ideology. Building on Michael Freeden’s seminal work on the topic , ideology can be understood as a clustered set of political concepts constituted around a problem definition, an offered solution or method, and a future vision of society.

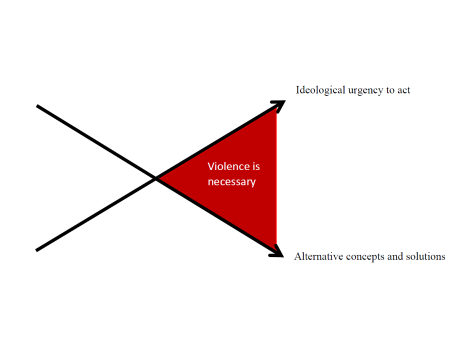

In the beginning of a typical radicalization process, certain societal, political or religious problems are defined and contextualized within an individual’s or group’s background and experiences to connect wider, global problems with micro-social issues. By raising the perceived importance of a given problem, other competing issues – ranging from everyday tasks such as exams or work to social issues such as unemployment, drug addiction or childcare – gradually become irrelevant. This tends to be achieved through targeted propaganda invoking and effectively altering individual values or political concepts. Calls for action to address the problem are often accompanied by the suggestion that a decreasing number of viable solutions and methods are available to tackle it. In the context of a continuously praised vision of a better future, alternative methods, solutions, and scenarios are systematically superseded.

When combined with certain kinds of ideologies, de-pluralization not only alters priorities about problems, solutions and goals, but restructures individual worldviews by determining the meaning of political values and concepts, such as ‘freedom’, ‘honour’, and ‘justice’. A maximally de-pluralized (and thereby radicalized) group or individual only recognizes problems, solutions and future scenarios associated with a specific ideology and does not perceive alternative frames and interpretations of core political values. This erasure of competing issues makes the need to address the problem appear increasingly urgent. In order to resolve the pressure this creates, violence comes to seem not just rational but necessary, especially if notions of human inequality are inherent in the underlying ideology. This suggests that some radicalized individuals need to act and behave violently – that beyond a certain point, other options are not visible or feasible to them. In certain ideological contexts, therefore, de-pluralization creates a kind of ‘ticking time-bomb’: a tension between a rapidly decreasing number of alternatives to solve a given problem and the increasing intensity of ideological calls for action – a tension that violence ultimately becomes the only way to resolve.

De-radicalization and re-pluralization

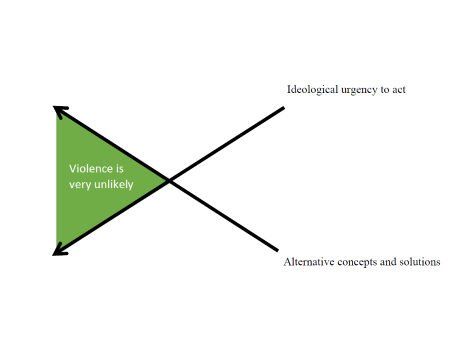

If radicalization leading to acts of violence and terrorism is essentially a de-pluralization process, counter-measures must be based on a process of re-pluralization that relieves the tension between the ideological urgency to act and the lack of alternative solutions. Usually this means balancing the given problem in relation to other equally important issues, while increasing the perceived number of viable solutions. This allows the individual to reprioritize problems and to choose from a variety of equally valid solutions. It also encourages reflection about whether a certain course of action is absolutely necessary, providing room for further intervention. Through positive and supportive personal relationships, mentoring, capacity building, education and other related methods, de-radicalization programs can reverse the vicious circle described above. In general, finding ways to keep individual and group perceptions about potential solutions to particular problems readily available can make efforts to prevent violent extremism more effective. The most effective efforts will address both the problem definition and the perceived solutions without negating the fundamental claim that there is a problem that needs to be addressed.

Implications for policy

With the growing threat posed by foreign fighters returning from the Syrian/Iraqi conflict, many Western countries have favoured specialized de-radicalization programs to counter possible violent radicalization processes in their early stages. Some countries, including Sweden, Germany and Denmark, have long traditions of such programs, mostly targeting Far-Right extremism. Many of these programs, however, are not based on coherent theories and methodologies, and their impact is rarely if ever evaluated. Yet understanding the basic dynamics of radicalization and de-radicalization, as outlined above, is little more than a starting point for the work of highly trained and experienced de-radicalization experts. Currently, only a small number of specialized training courses and experts capable of evaluating these programs exists. This is unfortunate because practitioners and policy-makers need to know that violent radicalization is not a one-way street and can be reversed even in its advanced stages. If understood, designed and supported appropriately, specially trained experts and programs can powerfully counteract home-grown terrorism and radicalization.

*Daniel Koehler is the Director of the German Institute on Radicalization and De-radicalization Studies (GIRDS) . His research focus lies on right-wing terrorism, radicalization and de-radicalization. He has studied religious studies, political science and economics at Princeton University and the Freie Universität Berlin