Russian Jurisprudence Survived Stalin But It May Not Survive Putin – OpEd

By Paul Goble

The increasing arbitrariness in the application of Russian law by the authorities threatens not only the well-being of the growing number of immediate victims of such actions but threatens the country as a whole because jurisprudence is a real as opposed to invented “binding” which holds Russia together, Vladimir Pastukhov says.

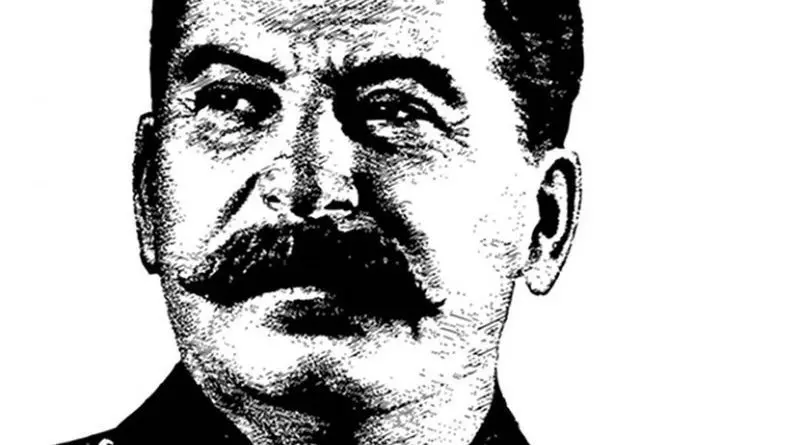

What is truly frightening is that the threat to jurisprudence in Russia is greater than at any time since it first emerged 150 years ago, the London-based scholar says. It survived Stalin despite all the duplicity that was displayed then, but there is a very real risk that it will not survive Putin (novayagazeta.ru/articles/2020/01/07/83366-prava-net).

because that is so, a demand for a legal state must become for Russia “the chief slogan” for the coming decade. 2019 became a year of transition when the state moved toward “open although still not massive but targeted” terror, a change “which has long-term consequences for the fates of Russia in the 21st century.”

“Arbitrariness kills not people; it in the first instance strikes at culture,” Pastukhov continues. “And if Russian civil society is not able to quickly and effectively conduct a ‘historic anti-terror’ operation, the present generation possibly will turn out to be ‘the last of the Mohicans’ of Russian civilization.”

day we are all witnesses of an unusual crime – the intentional murder of national culture which is being carried out as the result of a conspiracy of an organized group ofpeople from selfish motives. Alas, there is no such crime in the criminal code and thus there is no one to hold responsible for this.”

The challenge is this: “Law and legal order as a whole are the most important ‘social amino acid’ in the chain of the reproduction of culture.” If there isn’t enough of it, then “all normal social processes” slow down and stop and this “gradually leads to the complete cultural degradation of society.” After that follows “civilizational collapse.”

“Any civilization,” Pastukhov says, “including the Russia is a castle build on sand at the mouth of the river of history.” It takes centuries to build this castle but it can be destroyed “in a couple of decades.” Law is “the most important element of culture and a measure of the emancipation of society from the spontaneous forces of nature.”

Law is a necessary part of the fabric which holds a culture together, something that wise people and not just liberal democrats have recognized is a key to stability and growth. People may adopt good or bad laws, but “the formula ‘laws, not people must rule’ has a much deeper sense than many suppose.”

This formula means far more than just that people are treated equally. It means that they live within the framework of laws and that a system exists to ensure that those laws have a defined meaning rather than being given new content in the course of their application and that these laws embody a sense of justice shared by the population.

Pastukhov continues: “Society needed an instrument with the help of which people in each specific case could establish an objective justice not dependent on the individual will of anyone. Such an instrument is jurisprudence,” the science and practice of applying laws to specific cases.

“In its most general form,” he says, “jurisprudence is a ritual, a collection of strict and formalized algorithms,” the observation of which ahs the effect of “cleansing law from everything subjective and the influence of any individual will.” But that is missing in Russia today.

According to Pastukhov, “Russian law today can in a certain sense be called the most ‘free’ because each official is free to interpret the content of any Russian law as he wants and to his benefit.” It has thus “lost the quality of formal definiteness without which law ceases to be objective and is transformed into arbitrariness passed from one strong hand to another.”

“The mastery of judicial technique as a professional habit has lost its importance and been replaced by ‘legal cleverness.’” Those in the legal system are not so much concerned with legality but rather with credibility – and that only with those who have more power than they do, not with those who compare their actions with legal texts.

As a result, “the declared goals of legal creativity have lost all value” because the only thing that matters are the goals “which those who want to use these laws as an instrument of economic or political struggle” see as important.

Pastukhov stresses that “the most important element of the Western legal system is the rise of a special professional stratum of jurists and of a system of their preparation … In Russia, the rise of this stratum was connected with Aleksandr’s Judicial Reform of 1864; and since that time, it had developed, having survived even the era of ‘the Great Terror’ … But not today.”

Instead, the Russian scholar says, the rats have driven out the jurists, and the latter live only in the underground. Pastukhov first pointed to this danger in May 2008 (argumenti.ru/society/n131/37593 but now says his fears of a decade ago have been more than proven out.

Now, the rats have eaten the foundation of the legal system and returned Russian justice to what it was before Aleksandr II. In fact, this turning back to the past is much more serious and dangerous than it was even in “the worst Soviet times.” Then the regime was duplicitous, but it worked hard to preserve legal training and thus jurisprudence.

Soviet leaders even talked about “’a socialist legal state.’” But today, “the post-Soviet regime is latently terrorist but in its furnace are being destroyed the remnants of the legal tradition. The thread of legal culture has been broken. If this continues for several more years, Russian civilization will not be able to be restored either by democracy or dictatorship.”