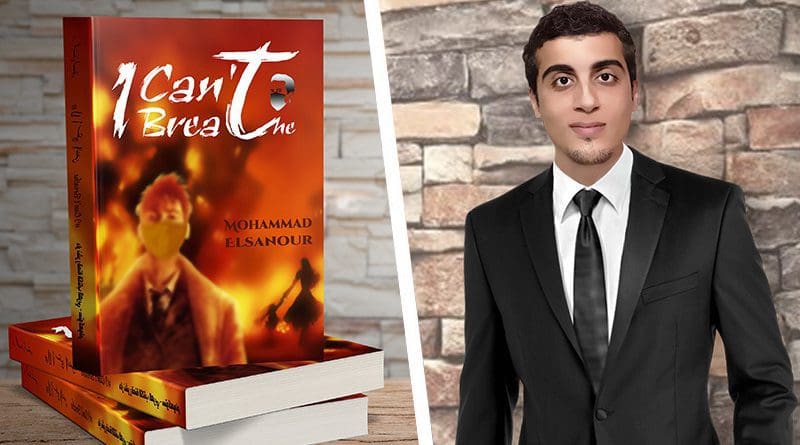

Mohammad Elsanour’s Novel ‘I Can’t Breathe’ – Book Review

Writing is an act of courage – to share a revelation of self, in an attempt to come to terms with personal insecurities, uncertainties, perplexities while making sense of life and hoping to arrive at some human truths. Many writers must have started out scribbling notes to themselves to express tensions, anxieties and hurts. The deepest notes in much fictional writing are, arguably, personal. Some writers admit this, some allude to the fact through metaphor, yet others dismiss it altogether. A few, who do not wish to connect their work to their private identities, for various reasons, use pseudonyms.

Mohammad Elsanour decided at the outset of his writing career that he needed to use a brave pen to write his novels, while admitting that they are all linked to our hardness life.

With the publication of his first novel ‘Louise Membership’, Elsanour had explicitly stated via his publishers-editors that the novel was an important experience that our community was (and still) going through after the official legalization of drugs in some countries, after the widespread use of drug addiction controls instead of marijuana and cocaine.

Elsanour’s last Novel “I Can’t Breathe” remain the core of his work to date. It is a powerful meditation on the way that victims of racism & wars hopes and fortunes were (and still are) constrained by to be free from racism and death. Feras Al Halabi, Syrian physician, is a man whose ingenuity and dexterity far surpass the circumscribed opportunities available to him. Despite this, he suffered many tragedies that forced him to send part of his family to seek refuge in Turkey, while the rest of them died from the effects of the war in Syria, and the other died with him in Egypt due to Corona pandemic infection. In the middle of 2020, he and his Nigerian friend moved to live in the United States of America, then they discover the great racism and unjustified violence against blacks that caused the death of many blacks victims along with the white supporters and protesters, among who died was his friend, the Nigerian doctor, who died due to racism.

While I Can’t Breathe is set in the early 2020 year, the questions it raises are deeply resonant today. Among them: What if African Americans responded to the profound violence leveled against them with vengeance instead of nonviolence? And what if the president or the government did not succeed in reducing tension between everyone at the time of the spread of the Corona pandemic?

I Can’t Breathe reminds readers that people are not always as they seem and that buried just below the surface of obsequiousness may be a thick layer of malice and an unquenched thirst for revenge. We do not need a new planet to live in safety with new rules above it that protect humanity from the wrong laws that we have previously set. Rather, we can exploit many deserted areas, develop our planet and protect it from racism, hatred and wars, so that everyone can live in peace and tranquility with each other.

I Can’t Breathe underscores the necessity of revisiting the violence that has been done to African Americans and the ways that language falls short of fully capturing its magnitude. Feras Al Halabi interweaves the macabre backstories that drive each of the Black characters up north, rendering the dark side of the Great Migration. The novel also explores whether anyone is truly who they seem to be, and moreover, whether people can truly know themselves and their intentions. Elsanour’s characters and their stories suggest that we are both less and more terrible than we think, and that our view of events directly correlates to our role in them.

Elsanour crafts unforgettable characters and masterfully builds suspense. The author also deftly deploys the frame story, putting the present narrative in conversation with the violent events of the childhood of the sons of Al Halabi in front of the Orontes River in Syria and the story of the ancient currency that linked both Egypt and Syria when they united in the United Arab Republic from 1958 until 1961 and Syria separated after that. Al Halabi’s intense reaction to the fictional retelling of his primal loss reminds readers that history belongs to those who control its narrative, and that fiction can be as powerful, and in some cases even more influential, than fact. While there is much to enjoy in I Can’t Breathe, the ending goes off the rails a bit, with too many minor characters and plot points introduced too swiftly. Among the fascinating characters who go underexplored are The elder man Abu Shihab, who supported his friend Al Halabi a lot and opened his restaurant in partnership with Al Halabi in Egypt until he died from the Corona infection, he and Al Halabi’s son.

The big shock lies in the phone call between Al Halabi in Egypt and his wife in Turkey after he learned that she had married another man (after learning of his false death in the war)and that his daughter Amal no longer recognized him, and that her primary language became Turkish and not Arabic, which made Al Halabi regret a great deal after his daughter Amal lost her origins. And her language is Arabic, and she no longer knows her real father, and Al Halabi was satisfied with confining that great sadness in his heart and not revealing that secret to anyone until his family congratulated him on living in safety and peace in Turkey.

On the other hand, Al Halabi wished that wars and racism would end that world, and everyone would return to live in safety and tranquility with each other without immigration, asylum, or travel to another planet, and to accommodate each other without the hatred that stems from an illusion that we ourselves have created.

I Can’t Breathe will resonate with readers who are interested in African and Arabs history and literature, and with those who want to interrogate the emblematic American myths of progress and individual uplift. The novel weighs questions that are central to human experience: how to live in trauma’s long shadow, the value and perils of vengeance, and the (im)possibility of ever fully knowing both others and ourselves.