Does The Philippines Need The EU’s GSP+? – Analysis

By FSI

By Uriel N. Galace*

The Philippines’ bilateral relationship with the European Union (EU) is one of its most longstanding and consequential diplomatic relationships. The Philippines benefits enormously from European trade, investment, and aid – not to mention, the political-security, socio-cultural, and development cooperation between the two sides.

However, ties between the two have recently become strained. The EU has harshly criticized the Duterte administration for its signature war on drugs. Moreover, the former has expressed misgivings about the latter’s attempts to legalize the death penalty and lower the criminal age of responsibility. In response, Duterte has rescinded European aid to the country to prevent it from being used by the EU as leverage to influence Manila’s internal affairs. As a result, the EU has threatened to impose economic sanctions on the country if it fails to address these concerns. In particular, it has threatened to withhold the Generalised Scheme of Preferences Plus (GSP+), a trade preference that allows the Philippines to export goods to the European market duty-free.

As of January 2018, the Philippines continues to retain its GSP+ preferential status following the release of a report from the European Commission that reviewed the Philippines’ progress in implementing 27 international conventions that it has ratified, a precondition for maintaining GSP+. The report noted that the Philippines had made progress on labor rights, environmental protection, gender equality, people trafficking, health, education, social-economic rights and the fight against corruption. Nevertheless, disagreements about the war on drugs, the legalization of the death penalty, and the lowering of the criminal age of responsibility may mean that the Philippines could still lose this trade advantage. The European Parliament convened last February 20 to discuss the report, after which a decision was reached to deploy a monitoring mission to the Philippines in the 2nd half of 2018.

In light of these realities, it is worth asking: how much does the Philippines benefit from the EU’s GSP+?

Looking at the data

GSP+ is a trade preference that allows for the duty-free entry of 6,274 Philippine products into Europe. This means that Philippine goods can enter the European market at a lower price, thereby rendering them more competitive. In return, the Philippines must commit to effectively implement 27 international core conventions covering labor rights, human rights, good governance, and environmental concerns.

According to the Head of the EU Delegation to the Philippines Franz Jessen, a record-high PHP 120B (EUR 2.0B) worth of Philippine exports benefitted from GSP+ in 2017, most of which were concentrated in the food and agricultural sectors. This amounted to a 21% increase from the previous year, where total exports stood at EUR 1.66B. The largest increases in 2017 were registered for animal products (+64%), fish and related products (+71%), prepared foodstuffs (+60%), edible fruits (39%), and also automotive parts (+45%), leather (+77%), textiles (145%) and footwear (+74%). This makes the EU the Philippines’ second largest export partner after Japan, and before the US and China.

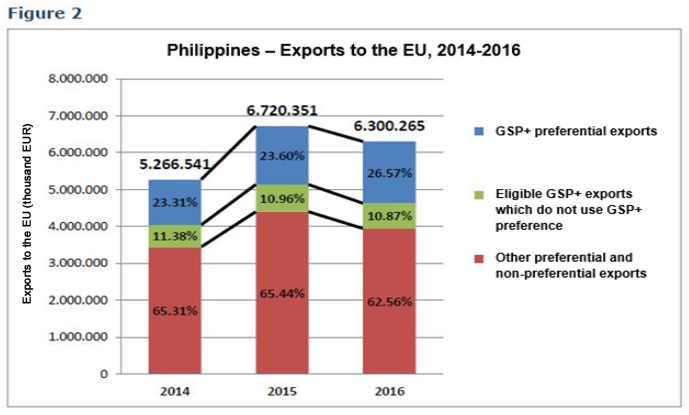

The Philippines has also increased its use of GSP+ preferences, which have grown 51% since 2012 and are now used for 26% of total exports. In 2016, the Philippines’ GSP preferential exports to the EU amounted to over EUR 6.3B. This resulted in a GSP+ utilization rate of 71%, making the economy one of the two biggest beneficiaries of the trade preference along with Pakistan. In 2017, that figure rose even further to EUR 7.57B, a 32.8% increase.

The Philippines has also increased its use of GSP+ preferences, which have grown 51% since 2012 and are now used for 26% of total exports. In 2016, the Philippines’ GSP preferential exports to the EU amounted to over EUR 6.3B. This resulted in a GSP+ utilization rate of 71%, making the economy one of the two biggest beneficiaries of the trade preference along with Pakistan. In 2017, that figure rose even further to EUR 7.57B, a 32.8% increase.

Source for data, charts, and tables: European Commission Assessment on Philippines GSP+

Analyzing the economic implications

The Philippine economy continues to grow at a robust pace, rising at an average rate of 6.6% from 2012 to 2017. This makes it one of the fastest growing economies in ASEAN and a star performer in a region that had recently been marred by a slowdown due to anemic global growth. Nevertheless, its external sector remains weak and reliant on a few key markets – particularly Japan, the US, China, and the EU – for its exports.

In the 1st half of 2017, total bilateral trade with the EU amounted to EUR 7.8B, a 17% increase from the year before, making the EU the Philippines’ 4th largest trading partner. Meanwhile, the EU is the largest foreign investor in the Philippines, with stocks in the country of over EUR 6.1B, as of 2015. This underscores how reliant Philippine firms are on the EU for capital.

Given that PHP 120B (2.3B USD) worth of Philippine exports benefitted from the GSP+ in 2016, and given that the Philippine economy’s GDP stood at 304.9B USD for the same year, it follows that GSP+ exports accounted for 0.7% of the country’s GDP –not an insignificant figure. Granted, losing GSP+ would not mean that the Philippines would lose all its exports to the EU. Nevertheless, this highlights how important GSP+ has been to boosting economic growth.

Furthermore, local communities in remote areas are the biggest beneficiaries of the GSP+. These include fishermen in General Santos City and coconut farmers in Lanao del Norte. As such, GSP+ has been essential not only for enhancing economic growth, but also for making it more inclusive, encouraging foreign investors to penetrate the Philippine market and provide employment opportunities for Filipino laborers.

Conclusion

All in all, the Philippines benefits considerably from the EU’s GSP+ preference. Although key exporters have publicly downplayed its significance, the fact that the government has worked behind the scenes to repair bilateral relations with the EU, in part to retain GSP+, is telling. Although losing it would be far from a death blow to the economy, and that it could, in theory, be compensated by increased economic ties with other trade partners like China, retaining GSP+ remains the best possible outcome for the country if it is serious about maximizing its growth. Consequently, Manila would do well to ensure that it keeps GSP+.

Ultimately however, despite the economic benefits gained by both parties from GSP+, whether or not the Philippines will retain the trade preference is going to be a political decision. This will be contingent on whether the two parties can work out their differences in perspective on matters such as human rights.

About the author:

*Uriel N. Galace is a Foreign Affairs Research Specialist with the Center for International Relations and Strategic Studies of the Foreign Service Institute. Mr. Galace can be reached at [email protected].

Source:

This article was published by FSI. CIRSS Commentaries is a regular short publication of the Center for International Relations and Strategic Studies (CIRSS) of the Foreign Service Institute (FSI) focusing on the latest regional and global developments and issues.The views expressed in this publication are of the authors alone and do not reflect the official position of the Foreign Service Institute, the Department of Foreign Affairs and the Government of the Philippines.