Oman: Reform, Security, And US Policy – Analysis

By CRS

By Kenneth Katzman*

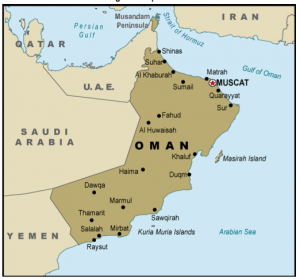

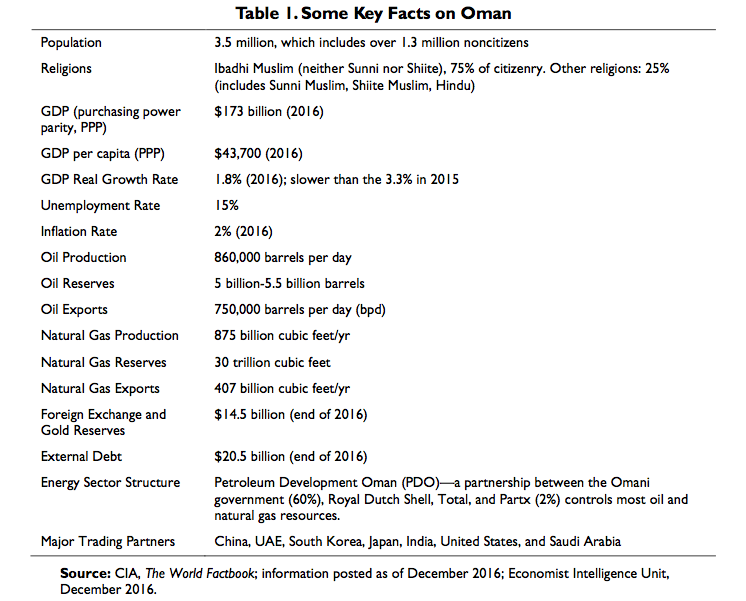

Oman is located along the Arabian Sea, on the southern approaches to the Strait of Hormuz, across from Iran. Except for a brief period of Persian rule, Omanis have remained independent since expelling the Portuguese in 1650. The Al Said monarchy began in 1744, extending Omani influence into Zanzibar and other parts of East Africa until 1861.

A long-term rebellion led by the imam of Oman, leader of the Ibadhi sect (neither Sunni nor Shiite and widely considered “moderate conservative”) ended in 1959. Oman’s population is 75% Ibadhi—a moderate form of Islam that is closer in philosophy to Sunni Islam than to Shiism. Sultan Qaboos bin Sa’id Al Said, born in November 1940, is the eighth in the line of the monarchy; he became sultan in July 1970 when, with British support, he forced his father, Sultan Said bin Taymur Al Said, to abdicate.

The United States has had relations with Oman from the early days since American independence. The U.S. merchant ship Ramber made a port visit to Muscat in September 1790. The United States signed a Treaty of Amity and Commerce with Oman in 1833, one of the first of its kind with an Arab state. This treaty was replaced by the Treaty of Amity, Economic Relations, and Consular Rights signed at Salalah on December 20, 1958. Oman sent an official envoy to the United States in 1840. A U.S. consulate was maintained in Muscat during 1880-1915, a U.S. embassy was opened in 1972, and the first resident U.S. Ambassador arrived in July 1974. Oman opened its embassy in Washington in 1973.

Sultan Qaboos was accorded formal state visits in 1974, by President Gerald Ford, and in 1983, by President Ronald Reagan. President Bill Clinton visited Oman in March 2000. Career diplomat Marc Sievers has been Ambassador to Oman since late 2015.

Democratization, Human Rights, and Unrest

Oman remains a monarchy in which decisionmaking still is largely concentrated with Sultan Qaboos. Throughout his reign, Qaboos has also formally held the position of Prime Minister, as well as the positions of Foreign Minister, Defense Minister, Finance Minister, and Central Bank Governor.

Other officials serve as “Ministers of State” for those portfolios and perform as ministers de-facto. Qaboos’s government, and Omani society, reflects the diverse backgrounds of the Omani population, many of whom have long-standing family connections to parts of East Africa that Oman once controlled, and to the Indian subcontinent.

Some senior Omanis argue that a formal position of Prime Minister is needed to organize the functions of the government and enable the Sultan to focus on larger strategic decisions. Should such a post be established, potential candidates include the deputy prime minister for Cabinet Affairs Fahd bin Mahmud Al Said,1 who is commonly referred to as “Prime Minister,” and the secretary general of the Foreign Ministry, Sayyid Badr bin Hamad Albusaidi, who is said to be efficient and effective2 and has given speeches publicly articulating Omani foreign policy. Another figure considered effective is an economic adviser to the Sultan, Salim bin Nasir al- Ismaily, a businessman and philanthropist who reportedly brokered the 2013 U.S.-Iran meetings discussed below.3 Another potential appointee is Royal Office head General Sultan bin Mohammad al-Naamani.

Along with political reform issues, the question of succession has long been central to observers of Oman. Qaboos’s brief marriage in the 1970s produced no children, and the sultan, who was born in November 1940, has no heir apparent. According to Omani officials, succession would be decided by a “Ruling Family Council” of his relatively small Al Said family (about 50 male members).

If the family council cannot reach agreement within three days, it is to base its succession decision on a sealed Qaboos letter to be opened upon his death; there are no confirmed accounts of whom Qaboos has recommended. The succession issue has come to the fore since mid-2014 when he left Oman to undergo medical treatment in Germany, reportedly for colon cancer.4 Then-Secretary of State John Kerry met with Qaboos in Germany in January 2015, and the Sultan returned to Oman in late March 2015. Since then, he has not left Oman and has appeared in public on only a few major occasions, such as Oman’s national day (November 2015) and the February 15, 2017, visit to Oman of Iranian President Hassan Rouhani.

Potential Successors. The leading contenders to succeed Qaboos include three brothers who are cousins of the Sultan and whose sister was the woman who was briefly married to Qaboos. They are Minister of Heritage and Culture Sayyid Haythim bin Tariq Al Said, whom some assess indecisive; Asad bin Tariq Al Said, a former military officer who has held the title of “Representative of the Sultan” for several years; and Shihab bin Tariq Al Said, the former commander of Oman’s Navy. All are in their 60s. Asad bin Tariq appeared to become a frontrunner as a potential successor in March 2017 when he was appointed deputy prime minister for international relations and cooperation affairs and represented Oman at an Arab League summit in Jordan. Another potential choice is Fahd bin Mahmud,5 who had previously regularly represented Oman at major regional and international meetings.

Expansion of Representative Institutions and Election History

Many Omanis, U.S. officials, and international observers credit Sultan Qaboos for establishing consultative institutions and electoral processes before there was evident public pressure to do so. Under a 1996 “Basic Law,” Qaboos created a bicameral “legislature” called the Oman Council, consisting of the existing Consultative Council (Majlis As Shura) and an appointed State Council (Majlis Ad Dawla), established by the Basic Law.

The Consultative Council was formed in 1991 to replace a 10-year-old all-appointed advisory council. A March 2011 decree expanded the Oman Council’s powers to include questioning ministers, selecting its own leadership, and reviewing government-drafted legislation, but its scope of authority is still not equal to that of a Western-style legislature. It does not have the power to draft legislation or to overturn the Sultan’s decrees or government regulations. As in the other GCC states, formal political parties are not allowed. But, unlike Bahrain or Kuwait, well-defined “political societies” (de-facto parties) that compete within or outside the electoral process have not developed in Oman.

The electoral process has broadened consistently. The Consultative Council was initially chosen through a selection process in which the government had substantial influence over the body’s composition, but this process was gradually altered to a full popular election. When it was formed in 1991, the body had 59 seats, and was gradually expanded to its current 85 seats. Prior to 2011, the Sultan selected the Consultative Council chairman; since then, the chairman and a deputy chairman have been elected by the Council membership. Also in 2011, Qaboos instituted elections for municipal councils. Each province with a population of more than 30,000 elects two members, whereas a province with fewer than that elects one.

The electorate for the Consultative Council has gradually expanded. In the 1994 and 1997 selection cycles for the council, “notables” in each of Oman’s districts nominated three persons and Qaboos selected one of them to occupy that district’s seat. The first direct elections were held in September 2000, but the electorate was limited (25% of all citizens over 21 years old). For the October 4, 2003, election, voting rights were extended to all citizens, male and female, over 21 years of age. About 195,000 Omanis voted in that election (74% turnout). The same two women were elected as happened in the 2000 vote (out of 15 women candidates). In the October 27, 2007, election (after changing to a four-year term), public campaigning was allowed for the first time and about 250,000 people voted (63% turnout). None of the 21 females (out of 631 candidates) won. The more recent Consultative Council elections are discussed below.

Appointed State Council. The government considers the State Council as a counterweight to the Consultative Council, and it remains all-appointed. The Council, which had 53 members at inception, has been expanded to 84 members, nearly the size of the Consultative Council. By law, it cannot have more members than the Consultative Council. Appointees are usually former high- ranking government officials (such as ambassadors), military officials, tribal leaders, and other notables.

2011-2012 Unrest Cast Doubt on Satisfaction with Pace of Political Reform

The expansion of the electoral process did not satisfy those Omanis, particularly those younger and well-educated, who consider the pace of liberalization too slow, or those dissatisfied with the country’s economic performance. In July 2010, 50 prominent Omanis petitioned Sultan Qaboos for a “contractual constitution” that would provide for a fully elected legislature. In February 2011, after protests in Egypt toppled President Hosni Mubarak, protests broke out in the northern industrial town of Sohar, Oman, and later spread to the capital, Muscat. One person was killed in February 2011 by security forces. Although most protesters asserted that their protests were motivated primarily by economic factors, some echoed calls for a fully elected legislature.

Possibly corroborating the assertions of experts that Qaboos is highly popular among the citizenry, many protestors carried posters lauding his rule. Many older Omanis apparently did not support the protests, apparently comparing the existing degree of “political space” favorably with that during the reign of Qaboos’s father, Sultan Said bin Taymur. During his father’s reign, Omanis needed the sultan’s approval even to wear spectacles or to import cement, for example. Some experts argue that Sultan Said kept Oman isolated in an effort to insulate it from leftist extremism that gained strength in the region during the 1960s.

The government calmed some of the unrest through a series of measures, including clearing protesters from Sohar; expanding the powers of the Oman Council; appointments of several members of the Consultative Council as ministers; and the naming of an additional female minister. The Sultan also ordered that 50,000 new public sector jobs be created, that the minimum wage increase by about one-third (to about $520 per month), and that unemployed job seekers be granted $400. Qaboos issued a decree giving the office of the public prosecutor autonomy and consumers additional protections.

Even though protests largely ended by mid-2012, during that year, at least 50 journalists, bloggers, and other activists were jailed for “defaming the Sultan,” “illegal gathering,” or violating the country’s cyber laws. Twenty-four of them went on a hunger strike in February 2013 and the Sultan pardoned virtually all, an action praised by international human rights groups. In addition, Omanis who had been dismissed from public and private sector jobs for participating in unrest were reinstated.

The U.S. reaction to the unrest in Oman was muted, possibly because Oman is a key ally of the United States and perhaps because the unrest appeared relatively minor. On June 1, 2011, then- U.S. Ambassador Richard Schmierer told an Omani paper: “The way in which [Sultan Qaboos] responded to the concerns of the Omani people is a testament to his wise leadership.”6 At her confirmation hearings in July 2012, Ambassador-Designate to Oman Greta Holz said “… I will encourage Oman, our friend and partner, to continue to respond to the hopes and aspirations of its people.”

2011 and 2012 Elections Held Amid Unrest

The October 15, 2011, Consultative Council elections went forward despite the unrest. The enhancement of the Oman Council’s powers raised the stakes for the elections. There were of 1,330 candidates—a 70% increase from the number of candidates in the 2007 vote. A record 77 women filed candidacies. However, voter turnout (about 60%) was not higher than in past elections. The expectation of several female victors was not realized: only one was elected, a candidate from Seeb (suburb of the capital, Muscat).

Some reformists were heartened by the election victory of two political activists—Salim bin Abdullah Al Oufi, and Talib Al Maamari. In the vibrant contest for the speakership of the Consultative Council, Khalid al-Mawali, a relatively young entrepreneur, was selected. In the State Council appointments that followed the Consultative Council elections, the Sultan appointed 15 women, bringing the total female participation in the Oman Council to 16 out of 154 total seats—over 10%. The government did not permit outside election monitoring.

In 2012, the government also initiated elections for 11 municipal councils. Previously, only one such council had been established, for the capital region, and it was all appointed. The elected “councilors” make recommendations to the government on development projects, but do not make final funding decisions. The chairman and deputy chairman of each municipal council are appointed by the government. In the December 22, 2012, municipal elections, there were 192 seats up for election. There were more than 1,600 candidates, including 48 women. About 546,000 citizens voted. Four women were elected.

2015 Consultative Council Elections

Elections to the Consultative Council (expanded by one seat, to 85) were last held on October 25, 2015. The elected Consultative Council was. A total of 674 candidates applied to run, although 75 candidates were barred, apparently based on their participation in the 2011-2012 unrest. There were 20 female candidates. Turnout was estimated at 56% of the 612,000 eligible voters. The one woman on the Council was reelected and no other female was elected. As happened in 2011, only one woman was elected. Khalid al-Mawali was reelected Consultative Council chairman. On November 8, 2015, Qaboos appointed the 84-seat State Council, of whom 13 were women.

December 2016 Municipal Elections

On December 25, 2016, the second municipal elections were held to choose 202 councilors—an expanded number from the 2012 municipal elections. There were 731 candidates, of whom 23 were women. Turnout was about 40% of the 625,000 eligible voters, according to the government. Seven women were elected, more than were elected in 2012 but still a small percentage of the 202 seats up for vote.

Broader Human Rights Issues7

According to the most recent State Department report on human rights, the principal human rights problems in Oman, other than the monarchical political structure, are limits on freedom of speech, assembly, and association, and restrictions on independent civil society. Other U.S. concerns include a lack of independent inspections of prisons and detention centers, arrests of government critics who use social media, insufficient protections from domestic violence, and labor conditions and abuses of foreign workers. U.S. and other reports generally credit the government with holding accountable security personnel and other officials for abuses, including prosecuting multiple corruption cases through the court system.

U.S. funds from the Middle East Partnership Initiative and the Near East Regional Democracy account (both State Department accounts) have been used to fund civil society and political process strengthening, judicial reform, election management, media independence, and women’s empowerment. In 2011, Oman established a scholarship program through which at least 500 Omanis have enrolled in higher education in the United States. Some MEPI funds have also been used in conjunction with the U.S. Commerce Department’s Commercial Law Development Program to improve Oman’s legislative and regulatory frameworks for business activity.

Freedom of Expression, Media, and Association

Omani law provides for limited freedom of speech and press, but the government generally does not respect these rights. Press criticism of the government is tolerated, but criticism of the Sultan (and by extension, government officials) is not. In October 2015, Oman followed the lead of many of the other GCC states in issuing a new royal decree prohibiting disseminating information that targets “the prestige of the State’s authorities or aimed to weaken confidence in them.” The government continues to prosecute dissident bloggers and cyber-activists under that decree and other laws. During July-August 2016, Omani authorities arrested three journalists of the Azamn daily newspaper, and shuttered the paper, for its series of articles accusing senior judicial officials of corruption. However, on December 26, 2016, an appeals court reversed the closing of the paper, overturned the September 2016 conviction of one of the journalists, and reduced the sentences of the other two.8

Private ownership of radio and television stations is not prohibited, but there are few privately owned stations. Satellite dishes have made foreign broadcasts accessible to the public. Still, there are some legal and practical restrictions to Internet usage, and only a minority of the population has subscriptions to Internet service. Many Internet sites are blocked, primarily for sexual content, but many Omanis are able to bypass restrictions by accessing the Internet by cell phone.

Omani law provides for freedom of association for “legitimate objectives and in a proper manner”—language that enables the government to restrict such rights in practice. A 2014 decree by the Sultan imposed a new nationality law that stipulates that citizens who join groups deemed harmful to national interests could be subject to citizenship revocation. Associations must register with the Ministry of Social Development, which is empowered to determine whether a group serves the interests of the country.

Trafficking in Persons and Labor Rights

Oman is a destination and transit country for men and women primarily from South Asia and East Africa who are subjected to forced labor and, to a lesser extent, sex trafficking. In October 2008, President George W. Bush directed that Oman be moved from a “Tier 3” ranking on trafficking in persons (worst level) by the State Department Trafficking in Persons report for 2008 to “Tier 2/Watch List.” The President’s upgrade was based on Omani pledges to increase efforts to counter trafficking in persons (Presidential Determination 2009-5). Oman was rated Tier 2 in the 2009- 2015 Trafficking in Persons reports. However, the report for 2016 downgraded Oman to Tier 2: Watch List on the grounds that the government did not demonstrate increasing efforts to address human trafficking during the previous reporting period. Similarly, the Trafficking in Persons report for 2017 kept Oman at Tier 2: Watch List, on the basis that, in the aggregate, it did not increase its anti-trafficking efforts compared to the previous reporting period.9 According to the report, Oman did identify more victims than the previous year, but conducted fewer investigations of traffickers compared to the prior year.

On broader labor rights, Omani workers have the right to form unions and to strike. However, only one federation of trade unions is allowed, and the calling of a strike requires an absolute majority of workers in an enterprise. The labor laws permit collective bargaining and prohibit employers from firing or penalizing workers for union activity. Labor rights are regulated by the Ministry of Manpower. The minimum wage for citizens is $845 per month, but minimum wage regulations do not apply to a variety of occupations and businesses.

Religious Freedom10

The 1996 Basic Law affirmed Islam as the state religion, but provides for freedom to practice religious rites as long as doing so does not disrupt public order. Civil courts replaced Sharia (Islamic law) courts in 1999. Recent State Department religious freedom reports have noted no reports of societal abuses or discrimination based on religious affiliation, belief, or practice. Non- Muslims are free to worship at temples and churches built on land donated by the government, but there are some limitations on non-Muslims’ proselytizing and on religious gatherings in other than government-approved houses of worship.

All religious organizations must be registered with the Ministry of Endowments and Religious Affairs (MERA). Among non-Muslim sponsors recognized by MERA are the Protestant Church of Oman; the Catholic Diocese of Oman; the al Amana Center (interdenominational Christian); the Hindu Mahajan Temple; and the Anwar al-Ghubairia Trading Co. Muscat (for the Sikh community). The government agrees in principle to allow Buddhists to hold meetings if they can find a corporate sponsor. Members of all religions and sects are free to maintain links with coreligionists abroad and travel outside Oman for religious purposes. Private media have occasionally published anti-Semitic editorial cartoons. In 2015-2016, to address crowded conditions in some non-Muslim places of worship, MERA is planning to use land donated by Sultan Qaboos for construction of a new building for Orthodox Christians, with separate halls for Syrian, Coptic, and Greek Orthodox Christians. The government has also approved new worship space for Baptists.

Advancement of Women

Sultan Qaboos has publicly emphasized that he considers Omani women vital to national development. Women now constitute over 30% of the workforce. The first woman of ministerial rank in Oman was appointed in March 2003, and, since then, there have been several female ministers in each cabinet. Oman’s ambassadors to the United States and to the United Nations are women. The number of women in Oman’s elected institutions was discussed above, but campaigns to establish a minimum number of women elected to the Consultative Council.

Below the elite level, however, Omani women continue to face social discrimination, often as a result of the interpretation of Islamic law. Allegations of spousal abuse and domestic violence are fairly common, with women finding protection primarily through their families. Omani nationality can be passed on only by a male Omani parent.

Foreign Policy/Regional Issues

Under Sultan Qaboos, Oman has pursued a relatively independent foreign policy, including sometimes diverging markedly from at least some of its GCC allies. Oman has generally avoided direct military involvement in regional conflicts and has maintained consistent high-level ties to Iran. Oman backed the deployment of the GCC’s joint “Peninsula Shield” unit to Bahrain in 2011 to help the Al Khalifa regime counter the Shiite uprising there, but Oman did not deploy its own forces to that mission. Similarly, Oman joined the U.S.-led coalition against the Islamic State, but did not conduct any airstrikes against that group. Nor did Oman join the Saudi-led Arab coalition fighting the Iran-backed Houthi forces in Yemen.

At a GCC leadership meeting in 2012, Saudi Arabia first advanced a plan for political unity among the GCC states as a signal of GCC solidarity against Iran. Oman vociferously opposed the plan,11 even going so far as to threaten to withdraw from the GCC entirely if the plan were adopted. Other GCC leaders are similarly concerned about surrendering any of their sovereignty, and, although the proposal was again referenced at the annual GCC summit in December 2016, the plan still has not been adopted. Some opinion leaders in Oman have publicly raised the possibility that the country might at some point hold a referendum on whether to stay in the GCC alliance.12 Again demonstrating its unwillingness to reflexively follow a Saudi lead, Oman did not join the Saudi-led move in June 2017 to isolate Qatar over a number of policy disagreements.

Oman supported Kuwait’s efforts to mediate a resolution of the dispute—efforts that are in concert with mediation by Secretary of State Rex Tillerson. As part of its role to support a diplomatic resolution, Oman’s top diplomat Yusuf Alawi visited Washington, DC, to meet with Secretary Tillerson on July 21, 2017, the visit coming one week after Secretary Tillerson’s Kuwait-based “shuttle diplomacy” effort to resolve the rift.

In 2007, Oman was virtually alone within the GCC in balking at a plan to form a monetary union. Lingering border disputes also have plagued Oman-UAE relations; the two finalized their borders in 2008, nearly a decade after a tentative border settlement in 1999.

Iran

Omani leaders differ sharply with many of their GCC allies in asserting that engagement with Iran better mitigates the potential threat from that country than does confrontation. This stance has positioned Oman as a mediator on several regional issues in which most of the GCC states are working against Iran’s allies or proxies. There are residual positive sentiments among the Omani leadership for the Shah of Iran’s support for Qaboos’s 1970 takeover and its provision of troops to help Oman end the leftist revolt in Oman’s Dhofar Province during 1962-1975, a conflict in which Iran lost 700 troops.

Oman has no sizable Shiite Muslim community with which Iran could meddle in Oman. Others attribute Oman’s position on Iran to its larger concerns that Saudi Arabia has sought to spread its Wahhabi form of Islam into Oman, whose citizens tend to practice the moderate Ibadhism.

Sultan Qaboos bucked U.S. and GCC criticism by visiting Tehran in August 2009 at the time of protests in Iran over alleged governmental fraud in declaring the reelection of President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad in the June 2009 election. He visited again in August 2013, after Iran’s President Hassan Rouhani took office. Rouhani visited Oman in 2014 and again on February 15, 2017, as part of an Iranian effort to begin a political dialogue with the GCC—an initiative that Oman has been central to, along with Kuwait. Sultan Qaboos made a rare public appearance to receive Rouhani. Following the Rouhani visit, Oman welcomed Kuwait’s Amir on a three-day visit to jointly plan efforts to enlist the other GCC countries in a dialogue with Iran.

In part to retain its ties to Tehran, Oman has not joined the Saudi-led coalition that is combatting the Houthi rebels in Yemen. Nor did Oman immediately join a Saudi announcement in December 2015 of a Muslim-nation “counterterrorism coalition” that excludes Iran and Iran’s allies, although Oman finally did join that initiative in December 2016, becoming the 41st member of the group. Oman was the only GCC state not to downgrade relations with Iran in January 2016 in solidarity with Saudi Arabia when the Kingdom broke relations with Iran in connection with the dispute over the Saudi execution of dissident Shiite cleric Nimr Al Nimr. Oman’s Minister of State for Foreign Affairs did condemn the Iranian attacks on the Saudi facilities.

In February 2016, Oman joined the other GCC states in declaring Lebanese Hezbollah to be a terrorist organization—an action that signaled that Oman opposes Iran’s nonstate allies. Oman did not join the other GCC states in taking the additional step of restricting travel by its citizens to Lebanon— an effort to restrict Hezbollah’s income.

Some experts and GCC officials argue that Oman-Iran relations, particularly their security cooperation, are undermining GCC defense solidarity. In 2009, Iran and Oman agreed to cooperate against smuggling across the Gulf of Oman, which separates the two countries. On August 4, 2010, Oman signed a security pact with Iran to cooperate in patrolling the Strait of Hormuz, an agreement that reportedly committed the two to hold joint military exercises.13 The two countries expanded that agreement by signing a Memorandum of Understanding on military cooperation in 2013. The two countries have held five joint exercises under these agreements, most recently a December 2015 joint naval exercise.14 In addition, in late 2016 U.S. officials reportedly expressed concern to their Omani counterparts that Iran might be taking advantage of its relationship with Oman, and of Oman’s porous border with Yemen, to smuggle weapons to the Houthi rebels in Yemen via Omani territory.15

Oman has benefitted from economic ties with Iran—ties that might further expand now that international sanctions on Iran’s economy have been lifted.16 Iran and Oman have jointly developed the Hengham oilfield in the Persian Gulf, with a total estimated investment value of $450 million. The field came on stream on July 11, 2013, and is producing about 30,000 barrels per day. The investment is estimated at $450 million, although the exact share of the costs between Iran and Oman is not known. The field can also produce a maximum of 80 million cubic feet per day of natural gas. The two countries have also discussed potential investments to further develop Iranian offshore natural gas fields that adjoin Oman’s West Bukha oil and gas field in the Strait of Hormuz. The Omani field began producing oil and gas in February 2009. During Iranian President Hassan Rouhani’s 2014 visit to Oman, the two countries signed a deal to build a $1 billion undersea pipeline to bring Iranian natural gas from Iran’s Hormuzegan Province to Sohar in Oman, where it will be converted to Liquified Natural Gas (LNG) and then exported.17 The Korea Gas Corporation is reportedly nearing agreement to build the pipeline.18

Iran reportedly envisions the joint expansion of Oman’s port of Duqm as providing Tehran with a major trading hub to interact with the global economy. Iran and Oman are conducting a feasibility study to construct a $200 million car production plant at Duqm, a joint venture between Oman and Iran’s Khodro Industrial Group.

Even during the period of maximum sanctions (2010-2015), the two countries conducted normal civilian trade, supplemented by the informal trading relations that have long characterized the Gulf region. Oman’s government is said to have long turned a blind eye to the smuggling of a wide variety of goods to Iran from Oman’s Musandam Peninsula territory. The trade is illegal in Iran because the smugglers avoid paying taxes in Iran, but Oman’s local government collects taxes on the goods shipped.19

Oman as a Go-Between for the United States and Iran

Far from criticizing Oman for its ties to Iran, U.S. officials have used the Oman-Iran relationship to develop ties to Iranian officials. Oman’s intermediation facilitated the November 24, 2013, interim nuclear deal (Joint Plan of Action) between Iran and the “P5+1” countries (United States, United Kingdom, France, Russia, China, and Germany). Press reports indicate that then-Deputy Secretary of State William Burns and other U.S. officials began secretly meeting with Iranian officials in early 2013—before the June 2013 election of the moderate Hassan Rouhani as Iran’s president—to explore the possibility of a nuclear deal. The meetings accelerated after Sultan Qaboos’s August 25-27, 2013, visit to Iran. Omani banks, some of which operate in Iran, were used to implement some of the financial arrangements of the JPA, such as the transfer to Iran of $700 million per month in hard currency proceeds from oil sales.20

Oman’s pivotal role continued during talks to achieve the July 14, 2015, Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) between Iran and the P5+1. During November 9-10, 2014, Secretary of State John Kerry met with Iranian Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif in Muscat to try to accelerate progress in the negotiations, followed one day later by a meeting in Muscat between the entire P5+1 and Iranian negotiators. Secretary Kerry’s meeting with the ailing Qaboos in Germany in January 2015 reportedly focused on the nuclear talks with Iran.21 An additional round of P5+1-Iran talks was held in Oman subsequently, and the JCPOA was finalized in July 2015. In December 2015, Oman hosted a meeting between two key negotiators of the JCPOA, Energy Secretary Ernest Moniz and head of Iran’s Atomic Energy Organization Ali Akbar Salehi, to discuss implementing the JCPOA. In November 2016, Iran exported 11 tons of heavy water to Oman in order to reduce its stockpile below the amount allowed in the JCPOA and remain in compliance with the terms of the agreement. The heavy water will likely eventually be sold to other buyers that use that product.

Oman also has been an intermediary through which the United States and Iran have exchanged captives. Oman brokered a U.S. hand-over of Iranians captured during U.S.-Iran skirmishes in the Persian Gulf in 1987-1988. In 2007, Oman helped broker Iran’s release of 15 sailors from close U.S. ally the United Kingdom, who Iran had captured in the Shatt al Arab waterway. U.S. State Department officials publicly confirmed that Oman helped broker the 2010-2011 releases from Iran of U.S. hikers Sara Shourd, Josh Fattal, and Shane Bauer, who allegedly strayed over the border from Iraq. Oman reportedly paid their $500,000 per person bail to Iranian authorities.22 In April 2013, Omani mediation obtained the release to Iran of an Iranian scientist, Mojtaba Atarodi, imprisoned in the United States in 2011 for procuring nuclear equipment for Iran. During a May 2013 visit to Oman, then-Secretary of State Kerry reportedly discussed with Qaboos possible Omani help in obtaining the release of U.S.-Iran nationals held by Iran and determining the fate of retired FBI agent Robert Levinson, who disappeared after visiting Iran’s Kish Island in 2007.

Cooperation Against the Islamic State Organization and on Syria and Iraq

Omani leaders, as do those of the other GCC states, assert that the Islamic State constitutes a major threat to the region. At a meeting in Saudi Arabia on September 11, 2014, all the GCC states joined the U.S.-led anti-Islamic State coalition. However, unlike several GCC states, Oman has not conducted airstrikes against the Islamic State. Oman offered the use of its air bases for the coalition, but Oman’s bases are far from Syria and Iraq and have not been used much for strikes.

In the Syria internal conflict, possibly because of its relations with Iran, Oman has refrained from intervening against Iran’s close ally, Syrian President Bashar Al Assad, and instead focused on mediation. Oman is not reported to have provided funds or arms to anti-Assad rebel groups in Syria. Oman did joint other Arab states in 2011 in suspending Syria’s membership in the Arab League and closing its embassy in Damascus.23 In August 2015, Oman hosted Syria’s foreign minister for talks on possible political solutions to the Syria conflict, and in October 2015, Omani Minister of State for Foreign Affairs Yusuf Alawi visited Damascus to convey a message from then-Secretary of State John Kerry to Assad.24 Oman attended the multilateral meetings in Vienna on the Syria conflict in late 2015, which included most of the GCC states, major European powers, Russia, China, the United States, and Iran. On November 6, 2015, Saudi Foreign Minister Adel Jubeir visited Muscat to discuss the conflicts in Syria and Yemen (a conflict in which Oman also has mediated). During February 2-3, 2016, Russia’s Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov visited Muscat to discuss Syria and other regional issues.

On Iraq, no GCC state has undertaken air strikes against the Islamic State fighters there. The GCC states have tended to resist helping the Shiite-dominated government in post-Saddam Iraq. Oman opened an embassy in Iraq after the 2003 ousting of Saddam but then closed it for several years following a shooting outside it in November 2005 that wounded four, including an embassy employee. The embassy reopened in 2007 but Oman’s Ambassador to Iraq, appointed in March 2012, is resident in Jordan, where he serves concurrently. Oman provided modest funds for Iraq’s post-Saddam reconstruction, a relatively small amount.

Yemen

Oman’s relations with neighboring Yemen have historically been troubled, and Oman’s concerns have increased as Yemen has again lapsed into conflict. A GCC-wide initiative helped organize a peaceful transition from the rule of Ali Abdullah Saleh in 2011-2012. However, Saleh’s successor, Abdu Rabu Mansur Al Hadi, was driven out of Sanaa in 2015 by Zaidi Shiite Houthi rebels and central authority disintegrated. The Yemeni affiliate of Al Qaeda, Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP), also continues to operate there. Oman has largely closed its border with Yemen since early 2016 and has built some refugee camps near the border.

Oman is the only GCC state that has not joined the Saudi-led Arab coalition which has fought since March 2015 to try to restore the Hadi government. Oman’s relative neutrality, coupled with Oman’s ties to Iran, has enabled Oman to host talks between U.S. diplomats and Houthi representatives and to broker the release of several Western captives from Yemen. In November 2016, a U.S. Marine veteran who was detained by the Houthis in April 2015 was released through Omani assistance, according to then-Secretary of State Kerry.25 Formal mediation talks between the Hadi government and the Houthis that took place from April to August 2016 were held in Kuwait, which is part of the Saudi-led military coalition in Yemen; Saudi officials apparently trust Kuwait as a mediator more than they do Oman. Oman’s reported inability or unwillingness to prevent Iran’s smuggling of weapons to the Houthis via Omani territory, discussed above, probably has increased Saudi doubts about Oman’s neutrality as a Yemen mediator, although Omani officials reportedly have pledged to try to prevent such illicit activity.

The current instability in Yemen builds on a long record of difficulty in Oman-Yemen relations. The former People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen (PDRY), considered Marxist and pro-Soviet, supported Oman’s Dhofar rebellion. Oman-PDRY relations were normalized in 1983, but the two engaged in occasional border clashes later in that decade. Relations improved after 1990, when PDRY merged with North Yemen to form the Republic of Yemen. In May 2009, Oman signaled support for Yemen’s integrity and the government of then-President Saleh by withdrawing the Omani citizenship of southern Yemeni politician Ali Salim Al Bidh, an advocate of separatism in south Yemen.

Policies on Other Conflicts

Libya. Oman did not play an active a role in supporting the 2011 Libyan uprising that overthrew Mu’ammar Al Qadhafi. Oman did not supply weapons or advice to rebel forces or fly any strike missions against Qadhafi forces. Oman did recognize the opposition Transitional National Council as the government of Libya after Tripoli fell on August 21, 2011. In March 2013, Oman granted asylum to Qadhafi’s widow and her and Qadhafi’s daughter, Aisha, and sons Mohammad and Hannibal,26 who reportedly had entered Oman in October 2012. Aisha and Hannibal are wanted by Interpol pursuant to a request from the recognized Libyan government, but Libya has not asked for their extradition. Omani officials said they were granted asylum on the grounds that they not engage in any political activities.

Egypt. The GCC has been divided on post-Mubarak Egypt. Qatar supported the 2012 election of Muslim Brotherhood leader Mohammad Morsi as the first elected post-Mubarak president, but Saudi Arabia and the UAE oppose the Brotherhood and supported the Egyptian military’s ouster of Morsi in July 2013. Oman did not take a distinct side in this rift, although it did criticize a postcoup crackdown on Brotherhood supporters. Oman has joined most of the other GCC states in building ties to the government of former military leader/elected President Abdel Fatah El Sisi.

Israeli-Palestinian Dispute and Related Issues

Taking a stand supportive of U.S. policy, Oman was the one of the few Arab countries not to break relations with Egypt after the signing of the U.S.-brokered Egyptian-Israeli peace treaty in 1979. All the GCC states participated in the multilateral peace talks established by the 1991 U.S.- sponsored Madrid peace process, but only Oman, Bahrain, and Qatar hosted working group sessions of the multilaterals.

Oman hosted an April 1994 session of the working group on water that resulted in the establishment of a Middle East Desalination Research Center in Oman. Participants in the Desalination Center include Israel, the Palestinian Authority, the United States, Japan, Jordan, the Netherlands, South Korea, and Qatar.

In September 1994, Oman and the other GCC states renounced the secondary and tertiary Arab boycott of Israel. In December 1994, it became the first Gulf state to officially host a visit by an Israeli prime minister (Yitzhak Rabin), and it hosted then Prime Minister Shimon Peres in April 1996. In October 1995, Oman exchanged trade offices with Israel, essentially renouncing the primary boycott of Israel. However, there was no move to establish diplomatic relations. The trade offices closed following the September 2000 Palestinian uprising. In an April 2008 meeting in Qatar, de-facto Foreign Minister Alawi informed his then Israeli counterpart, Tzipi Livni, that the Israeli trade office in Oman would remain closed until agreement was reached on a Palestinian state. Several Israeli officials reportedly visited Oman in November 2009 to attend the annual conference of the Desalination Center, and the Israeli delegation held talks with Omani officials on the margins of the conference.27 Oman offered to resume trade contacts with Israel if Israel agrees to at least a temporary halt in Israeli settlement construction in the West Bank. Israel has not consistently maintained such a suspension and Israel and Oman have not reopened trade offices. Oman publicly supports the Palestinian Authority (PA) drive for full U.N. recognition.

Defense and Security Issues

Sultan Qaboos, who is Sandhurst-educated and is respected by his fellow Gulf rulers as a defense strategist, has long seen the United States as the key security guarantor of the region. Oman’s approximately 45,000-person armed force is the third largest of the GCC states and widely considered one of the best trained. However, in large part because of Oman’s limited funds, it is one of the least well equipped of the GCC countries.

Because of his historic ties to the British military, Qaboos early on relied on seconded British officers to command Omani military services, and Oman bought British weaponry. Over the past two decades, British officers have become mostly advisory and Oman has shifted its arsenal mostly to U.S.-made major combat systems. Still, as a signal of the continuing close defense relationship, in April 2016 Britain and Oman signed a memorandum of understanding to build a base near Oman’s Duqm port, at a cost of about $110 million, to support the stationing of British naval and other forces in Oman on a permanent basis.28 Britain agreed to that arrangement even though, as noted above, Iran is involved in helping Oman develop Duqm.

Qaboos has consistently advocated expanding intra-GCC defense cooperation and for the GCC to cooperate with the United States. Oman was the first Gulf state to formalize defense relations with the United States after the Persian Gulf region was shaken by Iran’s 1979 Islamic revolution. Oman and the United States signed a “facilities access agreement” that allows U.S. forces access to Omani military facilities on April 21, 1980. Days after the signing, the United States used Oman’s Masirah Island air base to launch the failed attempt to rescue the U.S. Embassy hostages in Iran—although Omani officials complained that they were not informed of that operation in advance. Under the agreement, which was renewed in 1985, 1990, 2000, and 2010, the United States reportedly can use—with advance notice and for specified purposes—Oman’s military airfields in Muscat (the capital), Thumrait, Masirah Island, and Musnanah. Some U.S. Air Force equipment, including lethal munitions, is reportedly stored at these bases.29 The U.S. Marines and Royal Army of Oman annually (each winter) hold a two-week bilateral exercise (“Sea Soldier”) to enhance coordination between the forces.

Oman’s facilities contributed to U.S. major combat operations in Afghanistan (Operation Enduring Freedom, OEF) and, to a lesser extent, Iraq (Operation Iraqi Freedom, OIF). According to the Defense Department, during major combat operations of OEF (late 2001) there were about 4,300 U.S. personnel in Oman, mostly Air Force, and U.S. B-1 bombers, indicating that the Omani facilities were used extensively for strikes during OEF. The U.S. military presence in Oman fell to 3,750 during OIF (which began in March 2003) because facilities in GCC states that are closer to Iraq were used more extensively. During 2004-2011, Omani facilities reportedly were not used for air support operations in either Afghanistan or Iraq, and the numbers of U.S. military personnel in Oman were reduced to a few hundred, mostly Air Force.30 No GCC state contributed forces to OIF or to subsequent stabilization efforts in Iraq. Unlike Bahrain or UAE, Oman did not send military or police forces to Afghanistan.

For 2017, Oman has earmarked $8.6 billion for defense and security. That amount comes from estimated total 2017 government expenditures of $30 billion.

U.S. Arms Sales and other Security Assistance to Oman31

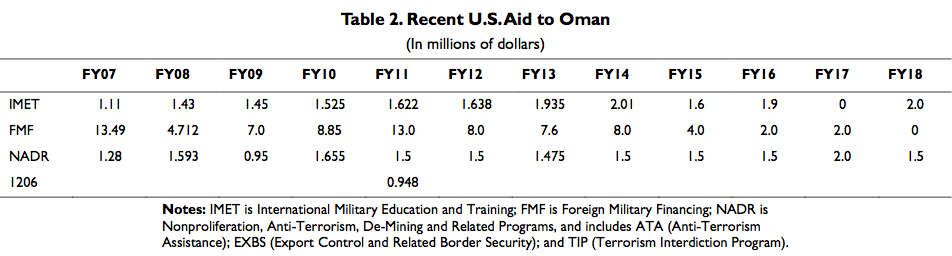

Using U.S. assistance and national funds, Oman is trying to expand and modernize its arsenal primarily with purchases from the United States. However, Oman is one of the least wealthy GCC states and cannot buy U.S. arms as readily as the wealthier GCC states can. Oman has received small amounts of Foreign Military Financing (FMF) that have been used to purchase equipment that helps Oman operate alongside U.S. forces, secure its borders, and combat terrorism. Oman is eligible for grant U.S. excess defense articles (EDA) under Section 516 of the Foreign Assistance Act. For the first time in any recent year, the Administration has not requested any FMF for Oman for FY2017, perhaps representing a shift toward emphasis on counterterrorism and border security assistance.

- F-16s: In October 2001, Oman purchased (with its own funds) 12 U.S.-made F- 16 C/D aircraft. Along with associated weapons (Harpoon and AIM missiles), a podded reconnaissance system, and training, the sale was valued at about $825 million; deliveries were completed in 2006. Oman made the purchase in part to keep pace with the other GCC states that bought U.S.-made combat aircraft. In 2010, the United States approved a sale to Oman of 18 additional F-16s, with a value (including associated support) of up to $3.5 billion.32 Oman signed a contract with Lockheed Martin for 12 of the aircraft in December 2011, with the purchase of an additional 6 possible. The first of the aircraft was delivered in July 2014 and the deliveries are to be completed by December 2016. Oman has also bought associated weapons systems, including “AIM” advanced medium-range air-to-air missiles (AIM-120C-7, AIM-9X Sidewinder), 162 GBU laser-guided bombs, and other equipment. Oman’s Air Force also possesses 12 Eurofighter “Typhoon” fighter aircraft.

- Countermeasures for Head of State Aircraft. In November 2010, DSCA notified Congress of a possible sale of up to $76 million worth of countermeasures equipment and training to protect the C-130J that Oman bought under a June 2009 commercial contract. The prime manufacturer of the equipment is Northrop Grumman. Another sale of $100 million worth of countermeasures equipment— in this case for aircraft that fly Sultan Qaboos—was notified on May 15, 2013.

- Surface-to-Air and Air-to-Air Missiles. On October 19, 2011, DSCA notified Congress of a potential sale to Oman of AVENGER and Stinger air defense systems, asserted as helping Oman develop a layered air defense system.

- Missile Defense. On May 21, 2013, Secretary of State John Kerry visited Oman reportedly in part to help finalize a sale to Oman of the THAAD (Theater High Altitude Area Defense system), the most sophisticated land-based missile defense system the United States exports. A tentative agreement by Oman to purchase the system, made by Raytheon, was announced on May 27, 2013, with an estimated value of $2.1 billion. However, a sale has not been announced. Several other GCC states have bought or are in discussions to buy the THAAD as part of an effort to establish a Gulf-wide missile defense network.

- Tanks as Excess Defense Articles. Oman received 30 U.S.-made M-60A3 tanks in September 1996 on a “no rent” lease basis (later receiving title outright). In 2004, it turned down a U.S. offer of EDA U.S.-made M1A1 tanks, but Oman asserts that it still requires armor to supplement the 38 British-made Challenger 2 tanks and 80 British-made Piranha armored personnel carriers it bought in the mid- 1990s. Oman has also bought some Chinese-made armored personnel carriers and other gear, and it reportedly is considering buying 70 Leopard tanks from Germany with a value of $2.2 billion.

- Patrol Boats/Maritime Security. Some FMF has been used to help Oman buy U.S.-made coastal patrol boats (“Mark V”) for antinarcotics, antismuggling, and antipiracy missions, as well as aircraft munitions, night-vision goggles, upgrades to coastal surveillance systems, communications equipment, and de-mining equipment. EDA grants since 2000 have gone primarily to help Oman monitor its borders and waters and to improve interoperability with U.S. forces. Oman has bought some British-made patrol boats. The United States also has sold Oman the AGM-84 Harpoon antiship missile.

- Anti-tank Weaponry. The United States has sold Oman anti-tank weaponry to help it protect from ground attack and to protect critical infrastructure. In December 2015, DSCA notified a potential sale to Oman of more than 400 TOW (tube-launched, optically tracked, wire-guided) anti-tank systems. The sale has an estimated value of $51 million. The United States also has provided to Oman 400 “Javelin” anti-tank guided missiles.33

Professionalizing Oman’s Forces: IMET Program and Other Programs

The International Military Education and Training program (IMET) program is used to promote U.S. standards of human rights and civilian control of military and security forces, as well as to fund English language instruction, and promote interoperability with U.S. forces. About 100 Omani military students participate in the program each year, studying at 29 different U.S. military institutions. For FY2016, some FMF was used to build Oman’s ability to address emerging threats to the anti-Islamic State coalition.34 The Obama Administration requested funds to continue those programs in FY2017.

Cooperation against Terrorism35

Since September 11, 2001, Oman has cooperated with U.S. legal, intelligence, and financial efforts against terrorist groups including Al Qaeda, Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP, headquartered in neighboring Yemen), and more recently the Islamic State organization. No Omani nationals were part of the September 11, 2001, attacks and no Omanis have been publicly identified as senior members of the Al Qaeda organization.

According to the State Department report on global terrorism for 2015 (latest available), Oman is assessed as actively involved in preventing members of these and other terrorist groups from conducting attacks and using the country for safe haven or transport.

”NADR” and Related Counterterrorism Funding. The United States provides funding— Nonproliferation, Antiterrorism, Demining, and Related (NADR) and other funds—to help Oman counter terrorist and related activity. NADR funding falls into three categories: Export Control and Related Border Security (EXBS) funds, Anti-Terrorism Assistance (ATA) funds, and Terrorism Interdiction Program funding. The U.S. Export Control and Related Border Security program (EXBS) has been used in recent years to train the Royal Oman Police (ROP), the ROP Coast Guard, the Directorate General of Customs, the Ministry of Defense, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Ministry of Transportation, the Ministry of Commerce and Industry, the Ministry of Transportation and Communication, and the Royal Army of Oman to enhance their capabilities to interdict weapons of mass destruction (WMD), advanced conventional weapons, or illegal drugs at official Ports of Entry on land and at sea ports and along land and maritime borders. ATA funds are used to train the Royal Army of Oman and several Omani civilian law enforcement agencies on investigative techniques, maritime border security, cybersecurity, and to enhance their ability to detect and respond to the entry of terrorists into Oman. For FY2017, the United States is providing Oman $1 million in NADR funds for counterterrorism programs (ATA) and $1 million to combat trafficking of WMD.

In 2005, Oman joined the U.S. “Container Security Initiative,” agreeing to prescreening of U.S.- bound cargo from its port of Salalah to prevent smuggling of nuclear material, terrorists, and weapons. However, the effect of some U.S. programs on Omani performance is sometimes hindered by the lack of clear delineation between the roles and responsibilities of Oman’s armed forces and law enforcement agencies.

There are no Omani nationals held in the U.S. prison for suspected terrorists in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. In January 2015, Oman accepted the transfer of three non-Omani nationals from Guantanamo Bay as part of an effort to support U.S. efforts to close the facility. On January 15, 2016, the Defense Department announced a transfer to Oman of 10 Yemeni nationals from the facility. In January 2017, Oman accepted another 10 Guantanamo prisoners.

Anti-Money Laundering. Oman is a member of the Middle East and North Africa Financial Action Task Force (MENA-FATF). Recent State Department terrorism reports credit Oman with transparency regarding its anti-money laundering and counterterrorist financing enforcement efforts and say that it has the lowest risk for terrorism financing or money laundering of any of the GCC countries. Oman does not permit the use of hawalas, or traditional money exchanges, in the financial services sector, and Oman has on some occasions shuttered hawala operations entirely. A 2010 Royal Decree was Oman’s main legislation on anti-money laundering and combatting terrorism financing but, in 2016, Royal Decree 30/2016 increased efforts to counter terrorism financing by requiring financial institutions to screen transactions for money laundering or terrorist financing. In 2015, Oman signed an agreement with India to improve cooperation on investigations, prosecutions, and counterterrorism efforts.

Countering Violent Extremism. According to the State Department report on terrorism for 2015, referenced earlier, “The nature and scope of Oman’s initiatives to address domestic radicalization and recruitment to violence are unknown, but it is suspected that Oman maintains tightly controlled and non-public CVE [countering violent extremism] initiatives in this area.” The department’s International Religious Freedom report, cited earlier, notes that the government continues to promote an advocacy campaign entitled “Islam in Oman,” that the government says is designed to encourage tolerant, inclusive Islamic practices.

Economic and Trade Issues36

Despite Oman’s efforts to diversify its economy, oil exports still generate over 50% of government revenues. Oman has a relatively small 5.5 billion barrels (maximum estimate) of proven oil reserves, enough for about 15 years at current production rates. In part because it is a relatively small producer, Oman is not a member of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC).

Recognizing that its crude oil fields are aging, Oman is trying to privatize its economy, diversify its sources of revenue, and develop its liquid natural gas (LNG) sector, for which Oman has identified large markets in Asia and elsewhere. Oman is part of the “Dolphin project,” operating since 2007, under which Qatar is exporting natural gas to UAE and Oman through undersea pipelines, freeing up Oman’s own natural gas supplies for sale to other customers. In December 2013, Oman signed a $16 billion agreement for energy major BP to develop Oman’s natural gas reserves. Gas revenues are estimated to account for about 20% of government revenues in Oman’s 2016 budget. Some of the joint ventures that Oman is engaged in with Iran in the oil and gas sector are discussed in the “Iran” section, above.

The downturn in energy prices since mid-2014 has affected Oman significantly. It ran a budget deficit well in excess of $12 billion in 2016—much wider than the $6.6 billion deficit for 2015. A deficit of about $7.7 billion is projected for 2017. Recognizing its budgetary limitations, the government is cutting subsidies substantially and it continues to try to increase private-sector and shrink government-sector employment. In February 2014, even before the oil price decline, the Omani government took further steps to address citizen unemployment by requiring that more than 100,000 jobs now performed by expatriates be transferred to Omani nationals, with the intention of reducing the proportion of expatriate private sector employment from 39% to 33%.

Oman is also trying to position itself as a trading hub, asserting that ships that offload in its Salalah port pay lower insurance rates than those that have to transit the Persian Gulf to offload in Dubai or Bahrain.37 The government reportedly is implementing a $60 billion project, with some funding coming from Iran and other countries as discussed above, to build up the port at Duqm (see Figure 1) as a transportation, energy, and military hub. Oman’s plans for the port include a refinery ($6 billion alone), a container port, a dry dock, and other facilities for transportation of petrochemicals. A planned transit hub would link to the other GCC states by rail and enable them to access the Indian Ocean directly, bypassing the Persian Gulf.38

U.S.-Oman Economic Relations

The United States is Oman’s fourth-largest trading partner, and there was nearly $3 billion in bilateral trade in 2016, down slightly from the $3.25 billion in trade in 2015. In 2016, the United States exported $1.78 billion in goods to Oman, and imported $1.1 billion in goods from Oman. Of U.S. exports to Oman, the largest product categories are automobiles, aircraft (including military) and related parts, drilling and other oilfield equipment, and other machinery. Of the imports, the largest product categories are fertilizers, industrial supplies, and oil by-products such as plastics. In part because of expanded U.S. oil production, over the past few years the United States has imported almost no Omani oil.39

Oman was admitted to the WTO in September 2000. The U.S.-Oman Free Trade Agreement was signed on January 19, 2006, and ratified by Congress (P.L. 109-283, signed September 26, 2006). According to the U.S. Embassy in Muscat, the FTA has led to increased partnerships between Omani and U.S. companies. General Cables and Dura-Line Middle East are two successful examples of joint ventures between American and Omani firms. These ventures are not focused on hydrocarbons, suggesting the U.S.-Oman trade relationship is not focused only on oil.

The United States phased out development assistance to Oman in 1996. At the height of that development assistance program in the 1980s, the United States was giving Oman about $15 million per year in Economic Support Funds (ESF) in loans and grants, mostly for conservation and management of Omani fisheries and water resources.

On January 23, 2016, the United States and Oman signed an agreement on cooperation in science and technology. The agreement paves the way for exchanges of scientists, joint workshops, and U.S. training of Omani personnel in those fields.

About the author:

*Kenneth Katzman, Specialist in Middle Eastern Affairs

Source:

This article was published by the Congressional Research Service (PDF)

Notes:

1 Author conversations with Omani officials in Washington, DC, June 2013.

2 Author conversation with Omani Foreign Ministry consultant and unofficial envoy. May 5, 2011. Sayyid Badr’s name is nearly identical to that of the Minister of State for Defense, but they are two different persons.

3 “Oman Stands in U.S.’s Corner on Iran Deal.” Wall Street Journal, December 29, 2013.

4 Simon Henderson. “Oman Ruler’s Failing Health Could Affect U.S. Iran Policy.” Washington Institute for Near East

Policy, November 7, 2014.

5 Author conversations with Omani officials in Washington, DC, June 2013.

6 http://oman.usembassy.gov/pr-06012011.html.

7 Much of this section is from the State Department’s country report on human rights practices for 2016 and other State Department reports on international religious freedom and on trafficking in persons. Human rights report for 2016: https://www.state.gov/documents/organization/265726.pdf.

8 http://www.gdnonline.com/Details/151483/Omani-court-overturns-ban-on-Al-Zaman-newspaper.

9 https://www.state.gov/documents/organization/271344.pdf.

10 For text of the section on Oman in the latest State Department report on International Religious Freedom (2015), see http://www.state.gov/documents/organization/258040.pdf.

11 Comments to the author by a visiting GCC official. May 2012.

12 “Oman ‘Not Leaving the GCC,’ Official.” Gulf News Report, June 27, 2016.

13 Iran, Oman Ink Agreement of Defensive Cooperation. Tehran Fars News Agency, August 4, 2010.

14 Giorgio Cafiero and Adam Yefet. “Oman and the GCC: A Solid Relationship?” Middle East Policy, 2016.

15 “Exclusive: Iran Steps up Weapons Supply to Yemen’s Houthis via Oman – Officials.” Reuters, October 20, 2016.

16 See CRS Report RS20871, Iran Sanctions, by Kenneth Katzman, for a discussion of U.S. sanctions on Iran.

17 Dana El Baltaji. “Oman Fights Saudi Bid for Gulf Hegemony with Iran Pipeline Plan.” Bloomberg News, April 21, 2014.

18 Oman: Iran’s Best Friend in the Gulf. Financial Times, April 11, 2017. 19 Ibid.

20 Omani banks had a waiver from U.S. sanctions laws to permit transferring those funds to Iran’s Central Bank, in accordance with Section 1245(d)(5) of the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2012 (P.L. 112-81). For text of the waiver, see a June 17, 2015, letter from Assistant Secretary of State for Legislative Affairs Julia Frifield to Senate Foreign Relations Committee Chairman Bob Corker, containing text of the “determination of waiver.”

21 Carol Morello. “Kerry Meets with Oman’s Ailing Sultan at His Estate in Germany.” Washington Post, January 11, 2015.

22 Dennis Hevesi. “Philo Dibble, Diplomat and Iran Expert, Dies At 60.” New York Times, October 13, 2011.

23 http://gulfnews.com/news/gulf/oman/oman-ready-to-mediate-between-syrian-parties-1.1617551.

24 Sigurd Neubauer. “Oman: the Gulf’s Go-Between” The Arab Gulf States Institute in Washington. February 4, 2016. 25 Adam Goldman. “Marine Veteran, Held a Year by Yemeni Rebels, is Freed.” New York Times, November 7, 2016.

26 “Muammar Gaddafi’s Family Granted Asylum in Oman.” Reuters, March 25, 2013.

27 Ravid, Barak. “Top Israeli Diplomat Holds Secret Talks in Oman.” Haaretz, November 25, 2009. http://www.haaretz.com/top-israeli-diplomat-holds-secret-talks-in-oman-1.3558.

28 “UK to Have Permanent Naval Base in Oman, MoU Signed.” Middle East Confidential. April 1, 2016. http://me- confidential.com/12289-uk-to-have-permanent-naval-base-in-oman-mou-signed.html.

29 Hajjar, Sami. U.S. Military Presence in the Gulf: Challenges and Prospects. U.S. Army War College, Strategic Studies Institute, p. 27. The State and Defense Departments have not released public information recently on the duration of the 2010 renewal of the agreements or modifications to the agreements, if any. The Khasab base, 50 miles from Muscat, was upgraded with $120 million in U.S. funds—assistance agreed in conjunction with the year 2000 renewal of the facilities access agreement. Finnegan, Philip. “Oman Seeks U.S. Base Upgrades.” Defense News, April 12, 1999.

30 Contingency Tracking System Deployment File, provided to CRS by the Department of Defense.

31 Section 564 of Title V, Part C of the Foreign Relations Authorization Act for FY1994 and FY1995 (P.L. 103-236) banned U.S. arms transfers to countries that maintain the Arab boycott of Israel during those fiscal years. As applied to the GCC states, this provision was waived on the grounds that doing so was in the national interest.

32 Andrea Shalal-Esa. “Lockheed Hopes to Finalize F-16 Sales to Iraq, Oman.” Reuters, May 16, 2011.

33 https://www.state.gov/t/pm/rls/fs/2016/253850.htm.

34 State Department Congressional Budget Justification for FY2016; and for FY2017.

35 Much of the information in this section is derived from the State Department Country Reports on Terrorism 2016, which can be found at https://www.state.gov/j/ct/rls/crt/2016/272232.htm.

36 For more information on Oman’s economy and U.S.-Oman trade, see CRS Report RL33328, U.S.-Oman Free Trade Agreement, by Mary Jane Bolle.

37 Author conversation with Omani officials. September 2013.

38 Hugh Eakin. “In the Heart of Mysterious Oman.” New York Review of Books, August 14, 2014. 39 http://www.census.gov/foreign-trade/statistics/product/enduse/imports/c5230.html.