Flashback To The Historic 15th UN General Assembly Session – OpEd

By IDN

By Mark Weisenmiller

The UN General Assembly will celebrate the 60th anniversary of its memorable 15th session in 2020. Never before in history had so many extraordinary historical and political leaders of a century been gathered in one place at the same time.

Yet for Frederick H. Bolan of Ireland (President of that General Assembly) and Dag Hammarskjold of Sweden (the then UN Secretary-General), the number of heads of state or government present – 32, by far the most at any one time in the history of the United Nations – was the least of their concerns.

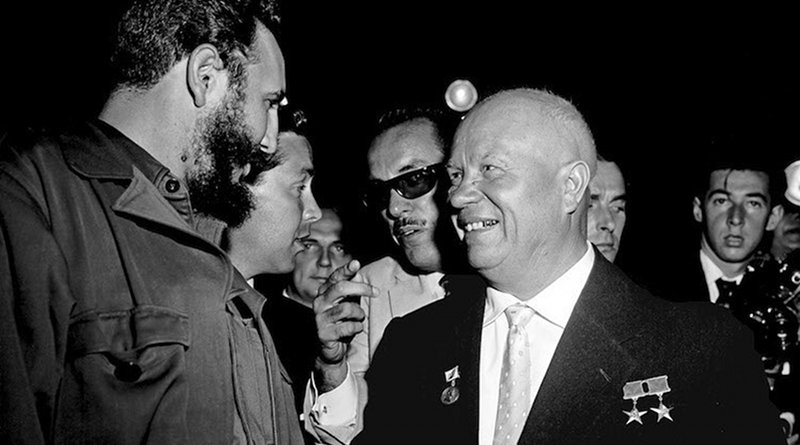

Among others, the leaders included Dwight Eisenhower of the United States, Nikita Khrushchev of the then Soviet Union, Harold Macmillan of Great Britain, Gamal Nasser of Egypt, Jawaharlal Nehru of India, Josip Tito of the then Yugoslavia, Fidel Castro of Cuba, Sukarno of Indonesia, Wladystaw Gomulka of Poland, Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana, John Diefenbaker of Canada, Robert Menzies of Australia and Janos Kadar of Hungary, not forgetting King Hussein I of Jordan; King Frederick IX of Denmark and Prince (later King) Sihanouk of Cambodia.

The weekly US news magazine ‘Time’ effusively wrote: “Not the pomp of ancient Rome or the jewelled brilliance of the great courts of France could shadow the moment. The eye of history could scarcely encompass the spectacle of so many potentates, presidents and dictators.” The ‘New York Times’ less gushingly described the scene as “the most momentous diplomatic gathering in history.”

In 1960, the so-called ‘Cold War’ between the United States and the Soviet Union was at its frostiest. The leaders of both countries were aware that the peoples living in nations then becoming independent, especially in Africa, were watching their actions closely.

One of the main issues discussed during the 15th Session of the General Assembly was the independence of numerous African countries in general as they broke away from their former colonial rulers, and the independence of the Belgian Congo (now Zaire) in particular.

As the General Assembly session started, four days after an emergency meeting to discuss the Congo crisis, no political leader knew the country’s destiny yet all realised that it could be influenced by US and/or Soviet Union leaders. Addressing the Assembly on September 22, 1960, Eisenhower said: “The people of the Congo are entitled to build up their country in peace and freedom. Intervention by other nations in their internal affairs would deny them that right and create a focus of conflict in the heart of Africa.”

The General Assembly would adopt the Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples on December 14, 1960, which guaranteed that colonial countries and peoples in independence nations would be recognised by the United Nations. This document, a milestone in the process of decolonisation, was recognised and followed by most world leaders, with the notable exception of those of the colonial powers.

Meanwhile, at the Assembly meeting, the world leader who made the greatest impact was Khrushchev. For reasons of security, while he was in New York, he was restricted to travelling only to and from the Soviet Embassy on Park Avenue and the Soviet UN Mission in Glen Cove, Long Island. This he did not take kindly to and on one occasion, standing on the patio of the Soviet Embassy, told a reporter standing on the street below: “I’m under house arrest … prisoners in prison have more space to stroll in.”

Relations between Khrushchev and Eisenhower had been strained following the shooting down of an American U-2 spy airplane flying over the Russian city of Sverdlovsk and the entourages for both men were careful that they did not accidentally meet in New York.

Despite Nasser, Nehru, Nkrumah, Sukarno, and Tito sponsoring a resolution requesting that Eisenhower and Khrushchev have a meeting at the United Nations, this never happened.

In his 1965 book ’Procession‘, American journalist and author John Gunther described some of Khrushchev’s actions while in New York:

“Mr. K described the Security Council as a spittoon, and as became famous, tore off his shoe during a speech at the Assembly, waving it and banging it on his desk. In shirtsleeves he conducted nocturnal interviews from his perch at the Soviet Embassy with newspapermen clamouring on the street twenty feet below, sang one night a few bars of the Communist hymn ‘The International,’ and even, in a mock gesture of respect, pretended to be leading an orchestra and ‘conducted’ a few passages from the ‘Star-Spangled Banner. He…compared some hostile demonstrators in the street to the material that one may find under a horse and when he was roundly booed by a group of fashionable dowagers at the Hotel Plaza, roundly shouted ‘Boo!’ to them in return.”

Like Eisenhower, Khrushchev also brought up the Congo when he said in a speech before the General Assembly: “The struggle which has been taken up by the Congolese people cannot be halted; it can only be slowed down or checked. But it will break out again with even greater force, and the people, having overcome all difficulties, will then achieve complete emancipation.”

His first speech to the Assembly lasted two hours and twenty minutes and before he left New York three weeks later, he would deliver ten more speeches there. In his first speech he castigated Hammarskjold “for pursuing the line of the colonialists” and then went on to propose that the office of the Secretary-General be replaced by a troika of leaders: one from Communist countries, one from Western countries, and one from independent nations.

Sitting behind Khrushchev during this speech, at a marble desk on a raised platform, was Hammarskjold. When Khrushchev finished, he turned and looked directly at the Secretary-General seeking some sort of physical reaction to his speech; Hammarskjold gave none. Using his office’s right to reply to any speaker, Hammarskjold then calmly explained why the office must continue to exist. This was met by a long standing ovation from numerous delegates, to which Khrushchev responded by pounding both of his fists on the desk before him.

One week later, on October 3, Khrushchev again mentioned the troika proposal in a speech and Hammarskjold said: “It’s very easy to resign, it’s not so easy to stay on.” The standing ovation and even greater applause he received this time so angered Khrushchev that he not only pounded his desk with both fists again but also took off one of his shoes and began striking the desk with it as well.

To those who complain that speeches by world leaders at the General Assembly last too long, the 15th session gave them ample justification. Apart from an exhaustive speech (almost eight hours long) by India’s V.K. Krishna Menon in 1957, the three longest speeches in General Assembly history were delivered at the 1960 session. In order of length, these were Castro’s 269-minute long speech, an address by Sekou Toure of Guinea that clocked in at 144 minutes, and Khrushchev’s aforementioned 140-miute long speech.

Most world leaders had left New York by early October and Khrushchev was seen as so monopolising the session that on October 6, his 18th day in New York, Columbia Broadcasting System (CBS) News reporter Daniel Schorr asked him: “Are you leaving soon?”

For many, Khrushchev is most remembered for what happened on October 12, 1960, He began the day in a good mood but when Lorenz Sumulong, a delegate from the Philippines, accused the Soviet Union of colonisation, Khrushchev went berserk. “Khrushchev leaped to his feet,” wrote author Peter Carlson in his 2009 book ‘K Blows Top’, “waving his hand and demanding a chance to respond. Frederick Boland, the Irish President of the General Assembly, agreed.”

Behind the speaker’s podium, Khrushchev called Sumulong “a fawning lackey of the American imperialists” and went back to his seat, whereupon Sumulong returned to the podium and continued his talk of Soviet Union colonisation. This made Khrushchev so mad that he took off his right shoe and began to rhythmically pound it on his desk. He then stood up and again asked Boland – who was becoming weary of the entire situation – for another chance to respond. Boland again agreed and Khrushchev appeared to calm down, even inviting Sumulong to visit the Soviet Union.

However, Rumanian delegate Edward Mezincescu took up Khrushchev’s cause in bellicose remarks. When Boland used his gavel to resume order, Mezincescu yelled even louder. Finally, Boland pounded his gavel so hard that its head broke off and flew over one of his shoulders. For the Irishman, enough was enough; he immediately called for a recess to restore order.

Still, Khrushchev was not done. In the final speech he ever gave at the United Nations, he called Eisenhower a liar and, as noted previously, described the Security Council as a spittoon.

He and Hammarskjold, the two most talked about leaders of the 15th session of the General Assembly, were to have painful, unpleasant fates.

Khrushchev was removed from his post in 1964, spending the remaining seven years of his life in a dacha, not far from Moscow, ceaselessly remembering past political triumphs. He died in 1971.

Hammarskjold was a mystical man who, as he grew older, continuously thought about God and death. One of his hobbies was writing poetry and one of the last pieces he wrote eerily seemed to forecast his premature death in a plane crash on September 18, 1961:

“The road, you shall follow it. The fun, you shall forget it. The cup, you shall empty it. The pain, you shall conceal it. The truth, you shall be told it. The end, you shall endure it.”