He Said, He Said: Russian, US Statements On Biden-Putin Call Differ Starkly – Analysis

By RFE RL

By Steve Gutterman*

(RFE/RL) — Amid a big Russian military buildup near Ukraine and on the Russian-controlled Crimean Peninsula, the Kremlin has kept a lot of people guessing about its plans and intentions.

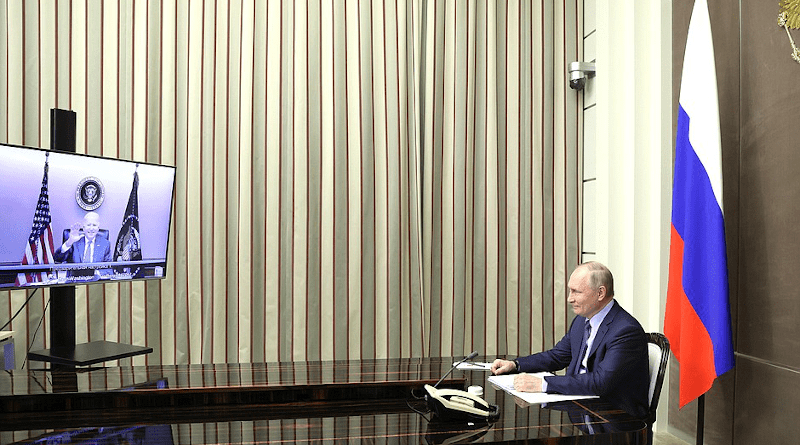

It did the same after President Vladimir Putin’s video call with U.S. President Joe Biden on December 7, issuing a statement about the talks nearly two hours after the White House released its readout.

When it came, one reason for the slower pace seemed clear: As has been the case several times in the past, the Kremlin readout was much longer than the White House statement. And it ranged decades back in time, making a reference to World War II and to a shared “special responsibility” for international security — wording that seemed designed to evoke the Cold War era and portray Russia and the United States as great powers whose weight in the world is equal.

Aside from being about the same meeting, the two statements had little in common, describing discussions of the same issues in strikingly different terms.

Example: Biden “voiced the deep concerns of the United States and our European allies about Russia’s escalation of forces surrounding Ukraine,” the White House said. In response, according to the Kremlin, Putin said that the United States must not blame Russia for tensions — and proceeded to blame NATO. In doing so, Putin made a baseless claim that the Western alliance “is making dangerous efforts to conquer Ukrainian territory” — something that Russia itself did when it seized Crimea in 2014.

The Kremlin said the talks were “frank and businesslike,” but a sense of tension seemed to ooze from that passage, which underscored how different the U.S. and Russian positions on the matters at hand have become.

The same disconnect was palpable in references to what seems to have been the only specific thing the two presidents agreed upon: There will be follow-up talks between U.S. and Russian officials.

But talks about what, exactly?

The accounts differed substantially in terms of content and context on this point, reflecting the starkly opposing positions on what is happening in Ukraine, as well as on security in Europe more broadly, and leaving the door wide open for disappointment and discord in the future.

The Russian readout suggested the follow-up talks would focus on what Moscow calls “security guarantees” that it has been seeking for years. In recent weeks, Moscow has pushed the issue with increasing insistence while also adding new details, making implicitly clear that the military buildup is aimed at least in part to get the West to comply.

Putin set out his demands in comments on December 1, saying that Russia will press for formal guarantees that NATO will not expand further eastward, including into Ukraine, and that unspecified “weapons systems posing a threat” to Russia will not be deployed “in close proximity” to its borders.

The Kremlin statement on the Biden-Putin call repeated those words with an adjustment on the weapons, saying that Russia “is seriously interested in receiving reliable, legally binding guarantees ruling out the eastward expansion of NATO” and the deployment of certain types of weapons in countries with which it shares borders.

“The leaders agreed to task their representatives with entering into detailed consultations on these sensitive issues,” it said.

Sensitive, indeed. The United States and NATO — not to mention Kyiv — say Russia cannot have a veto on Ukraine or any other country joining the Western alliance.

The White House statement put the agreement for talks in the context of Western concerns about a Russian threat to Ukraine.

Biden “reiterated his support for Ukraine’s sovereignty and territorial integrity and called for de-escalation and a return to diplomacy,” it said. “The two presidents tasked their teams to follow up, and the U.S. will do so in close coordination with allies and partners.”

- Steve Gutterman is the editor of the Russia Desk in RFE/RL’s Central Newsroom in Prague. He lived and worked in Russia and the former Soviet Union for nearly 20 years between 1989 and 2014, including postings in Moscow with the AP and Reuters. He has also reported from Afghanistan and Pakistan as well as other parts of Asia, Europe, and the United States.[email protected]