Can China Turn The Tide And Mend Its Reputation? – Analysis

By Nicholas Chiu

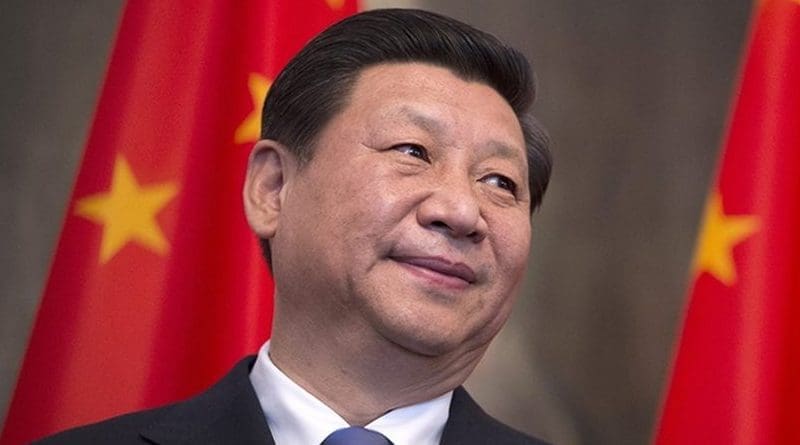

‘Against the wind, against the tides’ (‘ni feng ni shui’) was how Chinese President Xi Jinping described China’s 2020. The grim description is fitting, considering how China has fallen into disrepute for its initial handling of COVID-19, re-education camps in Xinjiang, the Hong Kong national security law, wolf warrior diplomacy and the bloody border clash with India.

Now that Joe Biden, a foreign affairs veteran vowing to restore US global leadership, has been inaugurated US president, a more challenging future lies before Beijing. But certain tides may help Beijing steer its way out of its current dilemma.

First, stable domestic politics gives Beijing greater leeway in foreign policy. Xi transforms moments of crises — including the pandemic, Yangtze basin floods and deteriorating US–China relations — into opportunities to unify the country around him. Despite speculation about a power struggle within the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), no apparent opposition has emerged, and critics have been ruthlessly expelled from the Party.

Domestic approval has given Xi enough credit to continue his rule as the CCP celebrates its 100th anniversary in 2021. According to a Global Times poll, 77.9 per cent of Chinese respondents believe that China’s global image has improved. Political chaos and COVID-19 mismanagement in Western countries have made the Chinese more confident in their political system. This indicates that Xi doesn’t need to make risky moves to secure his position.

The global alliance to counter China is also wobbly. Governments talk about reducing economic reliance on China, but industries aren’t as interested. A survey conducted by the American Chamber of Commerce in Shanghai revealed that 70.6 per cent of US businesses do not intend to shift production out of China. US-led efforts to decouple technology supply chains from China aren’t luring South Korean manufacturers away either.

Given that China is expected to generate over one third of global economic growth in 2021, the ‘China habit’ is more difficult to break. Ignoring US objections, the European Union signed a Comprehensive Agreement on Investment with China in December 2020. ‘Do we want to feel better or … trade better?’ asked the head of the European Chamber of Commerce in China, Joerg Wuttke. ‘We have to get real about how much we can shape China [on labour and human rights]’, he said. In addition to trade, Western countries’ pension funds need the positive real interest income from China’s government bond market.

Military cooperation against Chinese influence also has its limits. US officials are keen to balance out China’s A2/AD capabilities with mid-range missile deployments in the Asia Pacific, but allies such as Japan are reluctant to host them. South Korea’s economic suffering after hosting the Terminal High Altitude Area Defense missile system is a stark reminder of Beijing’s wrath.

The revival of the Quad — an informal strategic forum between the United States, Japan, Australia and India — raised hopes of forming an ‘Asian NATO’. But a formal military alliance is unlikely due to different national interests. Unless China significantly ramps up its military pressure, most Asian countries will still prefer hedging over containment.

The Biden administration may be more effective in cajoling allies, but China’s insurmountable edge over smaller powers makes its ‘divide and rule’ tactics sustainable. By smacking Australia with tariffs and reaching out to Japan, South Korea and New Zealand with promises of cooperation, Beijing is signalling that it is willing to hand out carrots, but will also readily use the stick on those who go against it.

Last but not least is the de-escalation of US–China relations. Though the great power competition is set to continue, there is room for cooperation. The Biden administration’s Special Presidential Envoy for Climate John Kerry acknowledged that Washington needs to talk with Beijing on climate change and has to ‘do it in a way that doesn’t force people into a corner to hunker down and head towards conflict’. If Biden is serious about developing green energy in the United States, he will need essential rare earths from China.

Given that current US tariffs and technology bans against China are expected to stay, negotiations will be tough. But even difficult engagement is better than outright conflict. Wall Street’s rush to the Chinese market means that the White House would be swarmed with lobbyists if US policy sabotages the Chinese economy and hurts growing US commercial interests in China.

During international backlash after the Tiananmen Square Incident in 1989, Deng Xiaoping, the then leader of China, addressed the CCP saying: ‘Fear not the world’s reactions or a loss of our international prestige — only when China succeeds in development … will we acquire genuine prestige’.

Like Deng, Xi believes China’s global standing depends on economic development, not political image. Despite assumptions that China is turning inwards with its ‘dual circulation’ strategy, Beijing’s actual intention is to upgrade its domestic market and further integrate into the global economy. Foreign containment and potential domestic unrest can only be resolved if China’s economic growth remains essential to everyone. If Beijing’s balancing act succeeds, it may eventually turn the tides.

*About the author: Nicholas Chiu is a political and cross-strait affairs researcher based in Taipei.

Source: This article was published by East Asia Forum