COVID-19: While The West Panicked, Some Asian Regimes Took A Different Path – Analysis

By MISES

By Mihai Macovei*

More and more voices are questioning the rationale for the general lockdown imposed in most of Europe and the US in response to the coronavirus epidemic. Such unprecedented suppression of civil and economic liberties during peace continue to strike many as hardly justified. Whether from a legal, ethical, or economic standpoint, we may soon find that the cost of the policy reaction was immense and grave. We have yet to see the real toll of the draconian confinement measures taken to stop the contagion. A high price must also be paid for the gargantuan financial and fiscal packages supposed to alleviate the impact of the largely self-inflicted economic crisis.

But not all regimes have taken this path. Several Asian countries at the epicenter of the COVID-19 outbreak, in particular Korea and Japan but also Taiwan and Hong Kong, have not instituted general lockdowns. Most reacted early with widespread testing, tracking, and isolating only those found positive for the virus. These countries were able to avoid a major contagion and the number of infections and fatalities have remained low so far. At the same time, social and economic activity have continued largely unobstructed. Korea is now widely hailed as a success story, whereas the self-declared victory of China is being questioned.

What Do Statistics Show?

It should be noted that health statistics are not fully comparable internationally with regard to both infected persons and fatalities. Countries are using different approaches to testing and tracing as well as various standards for classifying fatalities by cause. On top of these discrepancies, China’s official statistics are highly unreliable. Yet, corroborated with anecdotal evidence, they can still give us a broad picture.

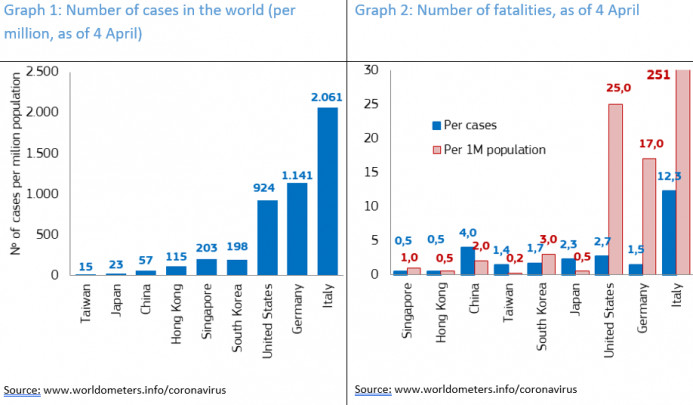

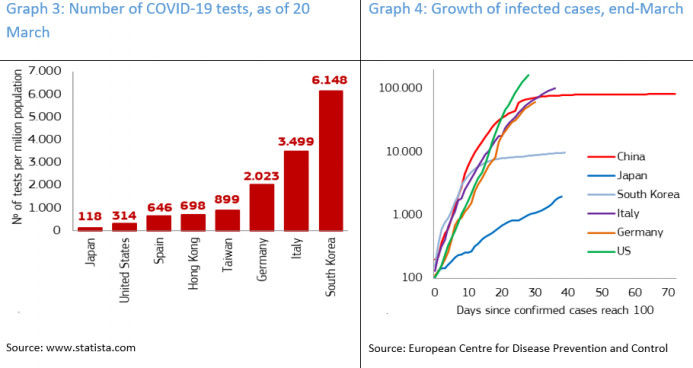

China’s initial reaction was slow and nontransparent. The first cases of the disease were identified in early December, but measures were not taken until one month later. Strict mobility restrictions and lockdowns were put in place, not only in the city of Wuhan and the Hubei region, but in the entire country. The number of confirmed cases increased exponentially until mid-February, after which it plateaued at about 80,000 cases (57 cases per million inhabitants, Graph 1), decelerating markedly in March (Graph 4). If accurate,1 the official number of fatalities remained limited at about 4 percent of cases (Graph 2). Nevertheless, both China’s official statistics and its alleged successful exit are seriously questioned. There are still new cases every day, and these could be imported, but could also stem from domestic unreported asymptomatic cases. Recently cinemas were closed after being reopened, and a small county in the Henan Province went into lockdown. These anecdotes fuel obvious fears of a possible second wave of infections, which represents an Achilles’s heel for a mass confinement strategy that prevents the majority of the population from building immunity against the virus.

Other Asian countries have managed to contain the spread of the disease so far, even though they did not follow China’s recipe. They have limited the number of infections to relatively low levels despite the fact that they performed many more tests on average (Graph 3). This is particularly the case with South Korea, which conducted more than 300,000 tests, with as many as 10,000 per day already by mid-March. They have also recorded very low numbers of fatalities, clearly outperforming not only Italy, Germany, and the US, but also China.Korea slightly exceeds China in terms of fatalities per population, but this could be explained by China’s less credible statistics. For now, China and Korea seem to be the only two major examples of countries that have mastered the outbreak, with the statistical caveats explained before (Graph 4). Japan’s number of new cases is still rising but rather slowly, which has puzzled health experts.

How Do Health Policies and Exit Strategies Differ?

Economic activity collapsed in China from January to February, following the draconian confinement measures.2 China’s leadership declared the lockdown a success, claimed victory in the fight against COVID-19, and gradually reopened social and economic life. However, many restrictions remain in place. Restaurants and shops are reopening, but most schools remain closed and strict social distancing rules still apply. Face masks and widespread temperature checks have become a norm. More widespread testing is pursued and a health color code system using big data is being rolled out, raising privacy issues and concerns about mass surveillance. Attention has shifted to imported cases, and foreigners have been largely banned from entering the country. As fears about a second infection wave persist, China appears to be exiting its lockdown only gradually.

In South Korea, both the government and the private sector reacted very quickly to the distressing news coming from China. As early as January, a private company developed a test for the coronavirus. and within three weeks the regulators approved it with unprecedented speed. This enabled Seoul to roll out a mass public testing program, including drive-through testing facilities, focused on anyone who may have been exposed to the virus. Those found positive were quarantined. The Korean government also conducted intrusive contact tracing to track known and suspected cases alike, using mobile providers and credit cards companies’ data and closed-circuit television (CCTV) networks. When contagion suddenly increased around a religious cult in Daegu, the government sealed it off rapidly. It also extended school and university holidays into late March and shut down religious, sports, and entertainment activities. At the same time, most factories, shopping malls, and restaurants have been kept open. Korea’s success also reflects a very high-performing and to a large extent private health sector, thoroughly upgraded after the MERS (Middle East respiratory syndrome) epidemics in 2015.

Japan was among the first countries to be hit by the coronavirus, but has not imposed a general lockdown and has not undertaken mass testing either.3 Despite the cancellation of sports events and the closure of schools, much of Japan’s life continued as normal until early April. There was no quarantine and no enforced closures of bars, clubs or restaurants. Workers still commuted instead of teleworking. Low testing rates may explain the low number of infections, but there is no other evidence of the disease’s spread in other ways, such as an overwhelmed health care system or high fatalities.4 It seems that Japan has done “just enough” in terms of social distancing and isolation of infected cases, given its culture of good hygiene and limited physical contact. On 7 April, PM Abe announced both a state of emergency over coronavirus and a record stimulus of about USD 1 trillion or 20% of GDP. The stricter measures seemed driven by political expediency and the need to justify the stimulus rather than the evolution of the epidemic. In any case, the new lockdown measures are the domain of local authorities which have the best information to impose them selectively. In addition, they don’t amount to a French-style lockdown as factories, distribution services and public transport are not stopped.

In Taiwan and Hong Kong5 there have been no general lockdowns either.6In general, the health response has focused on early testing, virus mapping, social distancing, and strict hygiene via intensive handwashing and wearing of masks. These countries closed borders and suspended travel from the infected countries. They also used digital technologies and big data to allow for precise live monitoring of the situation and disclosure of information to the general population. Hong Kong, for example, has turned to a police “supercomputer” normally used to investigate complex crimes to trace potential supercarriers and hot spots. All these countries seem to have benefited from a high level of preparedness after similar epidemic outbreaks in the past. Unlike in China, the exit out of the epidemic is likely to be smoother. Because people remain exposed to the virus, in particular the young people, who are likely to develop milder symptoms, herd immunity can be achieved faster. At the same time, widespread testing can help prevent a spike in contagion while social and economic life goes on largely as before. This approach can also mitigate the risk of subsequent waves of reinfection.

Conclusions

The experience of some Asian countries reinforces the arguments against the shutdowns imposed in most of Europe and the US. It shows that the respective governments could have pursued a different path, with likely lower numbers of cases and fatalities, had they been ready to take early and proportionate action. These governments can still change course and emulate the Korean approach rather than following in China’s footsteps, a country previously bashed for its authoritarian regime, nontransparent policies, and unfair competition practices. Concerns about privacy intrusion by using tracking technology should be carefully looked into. Yet such monitoring should be limited in time and probably is less harmful than placing the entire population in confinement. And in a case where a person who has tested positive for the virus represents a “palpable, immediate and direct threat”7 to the health of others, states are allowed to limit contact with that person within the boundaries of their property rights.

Everyone would like to minimize the risk of infections, the number of deaths, and the negative economic impact of the coronavirus epidemic. However, emotions and political interests should not take over a rational and balanced judgment of all risks involved. Almost two centuries ago, the French economist Frederic Bastiat argued that not looking into all the consequences of an action, including those not immediately seen, can make things worse. The shutdown will make the exit from the epidemic more difficult and at the same time magnifies already high government interventionism. As Mises explained, interventionism begets more of the kind until it ends in full socialism. Thus the war against the coronavirus can easily turn into a war against the overall well-being of the people.

*About the author: Dr. Mihai Macovei ([email protected]) is an associated researcher at the Ludwig von Mises Institute Romania and works for an international organization in Brussels, Belgium.

Source: This article was published by the MISES Institute

- 1.Other sources estimate the number of fatalities at about 45,000, fifteen times higher than the official number, only in Wuhan.

- 2.Industrial production dropped by 13.5 percent year over year (YOY), retail sales by 20.5 percent YOY, and fixed asset investment by 24.5 percent. Manufacturing Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI) dropped to 40.3 points while services PMI plunged to a record low of 26.5 in February.

- 3.As of April 9, a limited lockdown is being debated, although “cafés, restaurants and other facilities [are] open as usual on Thursday.”

- 4.Japan has a performant health sector with about thirteen hospital beds per thousand people, the highest among G7 nations.

- 5.Singapore announced stricter confinement measures, the equivalent of a partial lockdown on April 3.

- 6.Hong Kong, for example, has ordered restaurants to run at “half capacity.”

- 7.As Rothbard put it in The Ethics of Liberty.