Corruption In Chicago Before, During Prohibition Varied Based On Time, Position, Context

Corruption occurs when individuals criminally leverage their positions of power for financial gain. A new study examined how corruption varied by position of power and within criminal contexts by measuring the actions of corrupt players in Chicago before and during Prohibition. The study found that corruption by politicians, law enforcement, and others in organized crime varied by timeline (i.e., before and during Prohibition); the context of the crime; and individuals’ position and depth of involvement.

The study, by researchers at the University of California, Davis (UC Davis) and the University of Toronto (UofT), appears in Criminology, a publication of the American Society of Criminology.

“We found that everyday corruption was more frequent but less deeply embedded in corruption when criminal contexts were only moderately profitable,” explains Jared Joseph, a Ph.D. candidate in the sociology department at UC Davis, who coauthored the study. “However, as criminal contexts increased in profitability during Prohibition, corruption moved up the political ladder to include fewer people who were more deeply involved.”

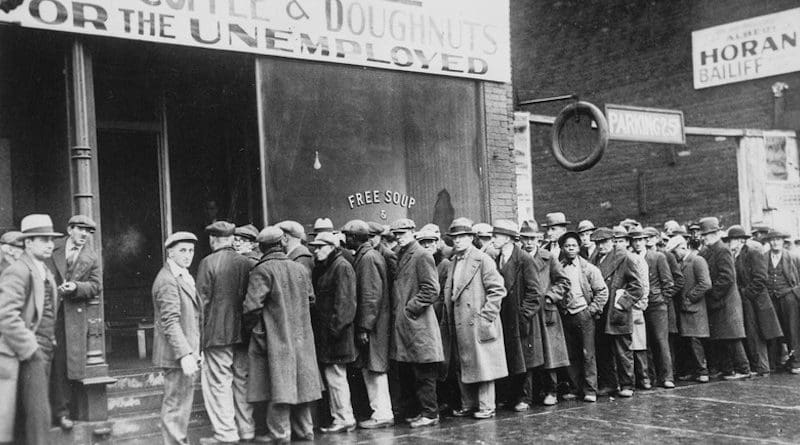

The connection between corruption and organized crime is well established in criminology, but studies on the topic have focused on the biggest players, with less attention to involvement by people in smaller roles. In this study, researchers compared Chicago’s organized crime network before Prohibition (1900-1919) to during Prohibition (1920-1933) to examine how the composition of corruption and the depth of individuals’ involvement changed when organized crime grew in size and centralized in power.

Data for the study came from the Capone Database, which includes archival material from the Chicago Crime Commission and other historical entities. The database is among the largest and most detailed relational databases on organized crime in Chicago; this study—the first to use the database to examine how embedded corruption was—measured organized crime as the largest component of criminal relationships before and during Prohibition.

In the pre-Prohibition period, Chicago’s organized crime network consisted of 267 individuals with 789 criminal relationships among them. During Prohibition, the network grew considerably, totaling 937 individuals with 3,250 criminal relationships among them, according to the study.

The researchers found that before Prohibition, more police were involved in organized crime than politicians, but the small group of politicians who were involved were more deeply embedded. During Prohibition, as the content, structure, and profitability of corruption changed, members of law enforcement engaging in crime decreased in proportion, dropping from 14 percent to 2.6 percent; they also became less embedded in organized crime and their positions were more randomly distributed. In contrast, politicians maintained their proportion (5 percent) in the organized crime network and also remained deeply embedded.

The study concluded that the larger and more profitable the criminal organization, the more likely corruption would involve fewer people who were more deeply embedded, and include individuals higher on the ladder of political influence.

One limitation of the study, the authors note, is that the Capone Database includes only known, recorded, preserved incidents of Chicago organized crime activity, and as such, may include inaccuracies and misinformation.

“Using public positions for personal gain is not a new phenomenon, but it is usually kept in the shadows of backroom deals and unexplained campaign contributions,” notes Chris M. Smith, assistant professor of sociology at the UofT, the study’s coauthor. “A fuller understanding of the mechanisms that allow illegal enterprises to flourish has implications for combating organized crime, corruption, and their overlap.”

The study was supported by the National Science Foundation as well as the National Institute of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice.