Is This The End Of Capitalism As We Know It? – Analysis

Does Capitalism have a future?

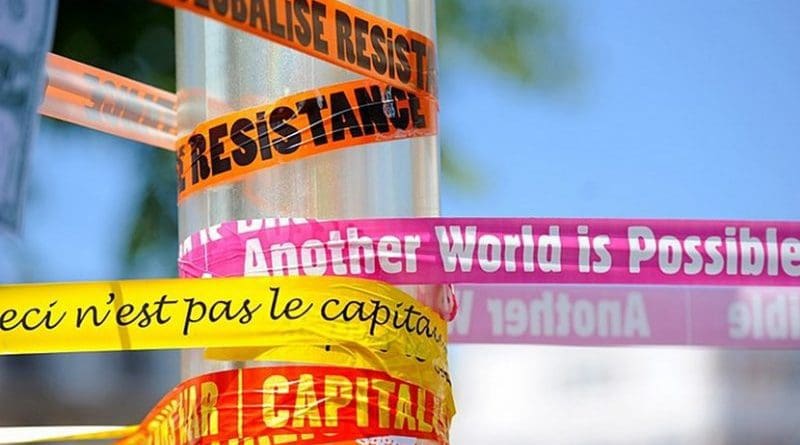

It has often been said that it is easier to think about the end of the world than the end of capitalism. However, this system is now showing signs of breaking down, which makes it possible to anticipate its imminent decline, not by prophecy, but much more simply by the social sciences. This is what five of the most eminent international researchers are demonstrating in an academic work entitled: “Does Capitalism Have a Future?”.

Revisiting Marx’s theory of predicting an inevitable collapse of capitalism. Academics Immanuel Wallerstein, Randall Collins, and to a lesser extent Craig Calhoun, have tackled this issue in the book “Does Capitalism Have a Future?”(1) Drawing on the social sciences and analyzing the springs of twentieth-century economic history, these Americans consider that the limits of this “world-system” will be reached in a few decades. A decline that would be “accelerated and multidimensional“.

In a language that they wanted to be accessible to all, based on the strong ideas of Marx, Braudel and Weber, they explore a series of “heavy” trends in contemporary societies, such as the deepening of economic and ecological crises, the probable decline of the middle classes, the contradictions and disarticulations of the international political system, and the problems of externalizing the social and environmental costs linked to the functioning of global capitalism. They also draw historical and sociological lessons from the fall of the Soviet bloc and the current changes in China.

For this group of prestigious scholars, the internal and external limits of the expansion of the capitalist “world system” are about to be reached. In the face of its accelerated and multidimensional decline, there is an urgent need to think seriously about what can and should succeed it. This requires thinking in unison about the traumatic consequences of the current mode of production and exchange and the alternatives that are likely to emerge in the coming decades. The book thus reminds us that the social sciences, when they rigorously explore reality, can also help to imagine another future.

Subtle rejection of capitalism

In presenting his wishes to the French people on December 31, 2018, the President of the French Republic, Emmanuel Macron, had this mysterious phrase:

“Ultra-liberal and financial capitalism, too often guided by the short term and the greed of a few, is coming to an end.”

At the UN, in September 2018, the words capitalism, ultra-liberal and financial capitalism were not pronounced. The 45-minute speech that ends with a thunderous “NO, I can’t cope with it” is a plea for joint and multilateral action against inequalities, and against the old recipes which, says the French President in New York, have shown their limits, but which he has nevertheless applied from the beginning of his term in France in the name of competitiveness (2):

“There is a trade war, so let’s lower workers’ rights, let’s lower taxes more and more, let’s nourish inequalities to try to respond to our trade difficulties. What does this lead to? To the reinforcement of inequalities in our societies and to the break that we are experiencing.”

This break, in September, was not yet wearing a yellow vest, but Emmanuel Macron, elected in the second round against the National Front, has never denied it since his election. And at the Davos Economic Forum, in January 2018, he ardently questioned, in front of those who benefit from it, the dominant economic logics:

“We made people believe that growth concerns everyone, we said: the more growth we have, all the problems are going to be solved in the emerging countries, the intermediate countries or the developed economies. This is not true because this growth is structurally less and less fair. All the international reviews show it, whether it’s multinational institutions, NGOs, there is a concentration on the richest 1% that is happening every time. What’s that got to do with it? The financialization of this globalization that has favored a concentration effect and new technologies, this economy of innovation and competence that I mentioned, because it is an economy of superstars”.

After 2008, financial capitalism became a repellent in international forums, as here in January 2010 in Davos again, Nicolas Sarkozy, then President of the French Republic argued vehemently (3):

“Purely financial capitalism is a drift that flouts the values of capitalism (…). So I believe, Professor Schwab (editor’s note: the founder of the World Economic Forum in Davos), that we have no choice. Either we will change by ourselves, or the changes will be imposed on us. By what? By whom? By economic crises, by political crises and by social crises. Let’s choose immobility and the system will be swept away, and it will have deserved it! “

Yes, at the rostrum capitalism no longer has an outspoken defender, and this sequence began with the financial crisis. Before 2008, when the French were scolding the French for their purchasing power, it was said that it was a problem of perception, not a reality, and that globalization was happy. Today, even the IMF makes repeated calls for fairer globalization (4), and world leaders regularly talk about “inclusive capitalism,” as opposed to non-inclusive capitalism.

Financial capitalism at its peak

Ultra-liberal and financial capitalism has not been swept away. It has been regulated, but it is more powerful than before the crisis. Today, systemic banks (too big to fail) weigh more than they did in 2008. According to a study entitled: “10 years after the collapse of Lehman Brothers, has systemic risk declined?(5) their aggregate balance sheet was $46,859 billion in 2011, it reaches $51,676 billion in 2017 (6). State indebtedness, which makes them dependent on the financial markets, has doubled and now stands at $64 trillion.

In the United States, tenants have recently become financial products called “single-family rental securities”. What is called “Shareholder value”, i.e. the share of the company’s profit that goes to shareholders, remains the dominant indicator of listed companies, and to say that it is problematic is to expose oneself to polemics that do not answer the question asked. Nevertheless, this financialized (7) capitalism is indeed in crisis since the 2008 crisis.

By the way, what is financial capitalism?

For this historical-pedagogical passage, I rely on a text written by the economist Michel Aglietta in 2018,entitled: Capitalisme: les mutations d’un système de pouvoirs (Capitalism: the mutations of a system of power.) (8)

Financialized capitalism appeared in the 1980s, replacing the contractualized capitalism that prevailed from 1950 to 1972. In these so-called glorious years, collective bargaining, social protection and financial regulation had made it possible to overcome the underemployment that prevailed between the two wars.

In 72, a series of events (detailed in the article above) led to an inflationary crisis that lasted 10 years… and led to a new type of capitalism, financialized capitalism, characterized by the deregulation of finance, the opening up of markets, the primacy given to shareholder value, and the use of debt to maximize it.

This capitalism has not disappeared, but it entered into crisis 10 years ago with the financial crisis. Just as contract capitalism experienced 10 years of inflationary crisis, before disappearing, financialized capitalism no longer fulfills its promises and could also disappear.

The accumulation of capital by the few that it generates becomes counterproductive, economically. The euphoria of the markets that preceded the crashes is hitting the real economy harder and harder each time, as in 2008, putting states into debt, and all this will not last forever.

This is why Emmanuel Macron can say that “ultra-liberal and financial capitalism is coming to an end“. Yes, it is true. But when and how will this end come about? No one knows and few venture to predict it, except Nouriel Roubini (an economist known to have predicted the 2008 crisis) in Les Echos: Les cinq ingrédients qui préparent la crise de 2020 (9).

At the UN, Emmanuel Macron promised that the G7 under French presidency in 2019 would make inequalities its priority. At Davos, he promised a reformed World Trade Organization, and even a rehabilitated International Labor Organization, which is 100 years old and has so little power. He even said that the race for the least taxed was “the death of the financing of common goods and the least sharing.” Everything has been said. Everything remains to be done. Otherwise, there is a strong fear that the appropriation by power of the elements of language proper to the critique of capitalism will also nourish the break he says he wants to repair. Perhaps this is already the case…

Will the pandemic signal the end of capitalism?

The time of neo-liberal capitalism, which relied on globalization, the reduction of the role of the state, privatizations and weak social protection, is over according to Patrick Artus, chief economist of the Natixis bank.

This is not an April Fool’s Fool. Very productive in his analyses, the chief economist of the Natixis bank Patrick Artus published a note (10) on March 30, 2020 in which he simply predicts “the end of neoliberal capitalism” because of the coronavirus crisis. In recent years, this economist has become accustomed to getting off the beaten track of mainstream thinking once in a while. In particular, in February 2018, he claimed loud and clear that “Marx was right“.(11)

But make no mistake, Patrick Artus does not predict any radical upheaval of the existing social order. By the end of neoliberal capitalism, he means an inflection of the way current capitalism functions. A capitalism that has banked on “globalization“, “the reduction of the role of the state and the fiscal pressure”, “privatizations“, and “the weakness of social protection” in certain countries, such as the United States.

To justify his remarks, the Natixis economist first of all makes a relatively consensual observation within the business world: “the coronavirus crisis has highlighted the fragility of global value chains: when production stops in one country, the whole chain is stopped“. After a shudder in recent years, the “de-globalization” of real economies should therefore clearly accelerate with the health crisis. And the economist predicts that “there will be a return to regional value chains, with the advantage of less fragility and risk diversification.”

Beyond private actors, public authorities are also thinking about relocating production. “The coronavirus crisis has made governments aware that a certain number of strategic products need to be produced nationally: medicines, of course, but also new technologies (electronics, telecoms…),” or even “equipment for renewable energies“. It is therefore to be expected that these industries will be “relocated and that industrial policies will be renewed.” A well-known example in support of this: “a situation of dependence such as that which exists for drugs vis-à-vis China or India will no longer be accepted,” he asserts.

End of fiscal austerity

Duly noted, but on these latter subjects, the economist only confirms a shift already announced by political (12) and economic leaders, at least in France. On the other hand, his other arguments are more open to discussion: first, Patrick Artus believes that the current crisis will simply lead to the “end of fiscal austerity and tax competition“. Why? Because this “crisis will bring to light the need for a sustainable increase in health care spending, business support, and unemployment compensation in all countries“.

According to him, there will above all be a generalized awareness “of the need for the entire population to benefit from adequate social protection“, that is to say, in concrete terms, “decent unemployment compensation” and “health coverage“. This will mechanically lead to a strengthening of social models and thus to an increase in public spending. However, if this were the case, “it will no longer be possible to aggressively lower taxes“. And this would at the same time mark the end of tax competition. In short, in Europe “budgetary austerity will therefore disappear,” the economist ambitiously advances. It is not certain that the countries of Northern Europe, first and foremost the Netherlands, are listening to him…

The crisis of state-financed capitalism

One can speak of a state-financed capitalism to describe the dominant model of economic organization on a global scale today, a little more than ten years after the 2008 crisis, even if one can discuss the relevance of this concept for China, which presents specific features (centrality and strict governance of the Communist Party, ideological mobilization, “socialist market economy”). (13)

In 2008, however, we became aware of the extent to which central banks and States, public institutions dominated by economic logic, are in fact keystones of the financialized world order: zero or even negative interest rates, quantitative easing, policies to stimulate the economy as soon as necessary, massive public indebtedness on the markets, favored by very low interest rates. In 2019, the policy-mix remains largely the result of the ideological and economic upheavals of 2008-2010.

The financial euphoria that has become more pronounced in the second half of 2010 in the dominant countries is largely dependent on an expansionary monetary policy from which central banks seem to be unable to escape. The current cycle is characterized by a very limited debt reduction by public actors, which is non-existent for private actors, which shows how fragile it is.(14)

This cycle illustrates the dependence of contemporary capitalism on exceptional monetary and financial conditions that have become the rule today. The rise of US protectionism, which threatens this euphoria, accentuates the strongest contradictions of global state-financed capitalism.

Conclusion

As an expression of the increasing porosity of the political field to the logics of the economic field, or even their “fusion” at the top of the social space, the interpenetration of the public and private sectors is characterized by more numerous circulations, as is the case of the finance inspectors, a small homogeneous group that manages to reproduce itself within a school system that is still very centralized and elitist.(15)

This system is currently under great strain, not least because of a growing awareness of the educational foundations of the rift between the ruling elites and the popular classes, but strategies are at work underground within the dominant classes to resist what appears to be a bad patch in the natural course of globalization.

The prospect of a globalized capitalism backed by mature liberal democracies, which was the dominant utopia of the 1990s, is now increasingly proving itself for what it has always been: a fantasy born of post-Cold War Western triumphalism, largely disconnected from the processes that affect the real political-economic world. The latter is more than ever a field of struggles and unstable forces stemming from the neoliberal revolution and financialization.

You can follow Professor Mohamed Chtatou on Twitter: @Ayurinu

Endnotes:

- Cf. Immanuel Wallerstein, Randall Collins, Michael Mann, Georgi Derluguian, and Craig J. Calhoun. Does Capitalism have a future? New York, New York: Oxford University Press USA, 2013.

- https://youtu.be/zzPPFzufbkE, Address by the President of the Republic to the United Nations General Assembly on September 25, 2018 in New York. Credits: United Nations, Department of Public Information, Audiovisual Library

- https://youtu.be/MPOCI1Klxl8 Nicolas Sarkozy’s speech at the Davos forum on January 27, 2010.

- https://www.lefigaro.fr/flash-eco/2018/12/05/97002-20181205FILWWW00029-lagarde-fmi-prone-une-mondialisation-plus-juste.php On Tuesday, December 4, 2018, IMF boss Christine Lagarde made a strong call for a renewal of international cooperation, fearing the advent of an “age of anger” where inequalities could soon surpass those of the “golden age” of capitalism in the 19th century.

- http://www.cepii.fr/CEPII/fr/publications/lettre/abstract.asp?NoDoc=11752

- Cf.also: Douglas W. Arner, Emilios Avgouleas, Danny Busch and Steven L. Schwarc . Systemic Risk in the Financial Sector: Ten Years After the Great Crash. Montreal, Quebec, Canada: McGill-Queen’s University Press, CIGI Press, 2019.

- Financialization is a term sometimes used in discussions of the financial capitalism that has developed over the decades between 1980 and 2010, in which financial leverage tended to override capital (equity), and financial markets tended to dominate over the traditional industrial economy and agricultural economics. Financialization describes an economic system or process that attempts to reduce all value that is exchanged (whether tangible or intangible, future or present promises, etc.) into a financial instrument. The intent of financialization is to be able to reduce any work product or service to an exchangeable financial instrument, like currency, and thus make it easier for people to trade these financial instruments. Workers, through a financial instrument such as a mortgage, may trade their promise of future work or wages for a home. The financialization of risk sharing is what makes possible all insurance. The financialization of a government’s promises (e.g., US government bonds) is what makes possible all government deficit spending. Financialization also makes economic rents possible.

- http://www.cepii.fr/CEPII/fr/publications/em/abstract.asp?NoDoc=10384

- https://www.lesechos.fr/04/10/2018/lesechos.fr/0302342477303_les-cinq-ingredients-qui-preparent-la-crise-de-2020.htm

- https://www.research.natixis.com/Site/en/publication/m5s-lx5Bbb92bmN3Rt3wlOH-FfouhppovZfIyfsy2hw%3D

- https://www.humanite.fr/patrick-artus-marx-avait-raison-lavertissement-dun-economiste-liberal-649955

- https://www.ouest-france.fr/sante/virus/coronavirus/game-changer-le-coronavirus-va-changer-la-donne-dans-la-mondialisation-selon-bruno-le-maire-6752150

- Cf. in particular, Rémy Herrera, Zhiming Long, La Chine est-elle capitaliste ? Paris, Éditions Critiques, 2019.

- This observation is shared today, even by promoters of the neo-liberal order to personalities such as Jean-Claude Trichet: https://www.lesechos.fr/idees-debats/cercle/pour-echapper-a-cette-crise-qui-vient-1123706.

- Cf. Pierre France, Antoine Vauchez, Sphère publique, intérêts privés. Enquête sur un grand brouillage, Paris, Les Presses de Sciences Po, coll. « Domaine gouvernance », 2017.