US Policy Towards Iran’s Economic Reintegration – Analysis

By Kia Rahnama*

On July 14, 2015, the P5+1, the European Union, and Iran reached an agreement under the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA). The agreement stipulated that all UN Security Council sanctions as well as all multilateral and national sanctions related to Iran’s nuclear program would halt in exchange for a commitment from Iran to roll back its nuclear activities.

Subsequently, on January 16, 2016, the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) issued its first report finding Iran in compliance with its international obligations under the agreement thereby triggering the removal of sanctions. Since then, similar finding by the Department of State has further assuaged concerns that misgivings by the country may undermine the deal. Yet the initial agreement and its relative success, despite contributing to the softening of tensions between Iran and many of the European allies, have not convinced the new Administration to continue partnership with Iran. The new Administration’s approach to trade with China remains equally unresolved. Future viability of U.S. partnership with both countries relies on outlining government-wide missions that can take advantage of the newly created diplomatic and political space between the countries and ensure that U.S. national interest is best served. There is time for forging an alliance that today might seem as amorphous as the transatlantic alliance might have when General George Marshall sketched out the Marshall Plan.

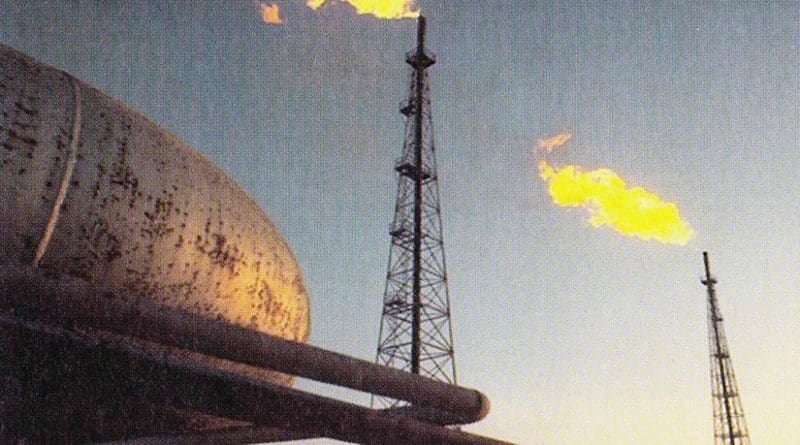

The United States government can play a supportive role in assisting the regional allies that desire economic partnership with Iran and china; this policy should contain Iran and China’s geostrategic ambitions but attempt direct any post-sanction economic goals toward those ends that serve peace and stability in the region. One such opportunity will include determining the U.S. policy towards Iran’s decision to reshape its energy sector and reinvigorate regional trade. More specifically, Iran has shown desire to join the “international liquefied natural gas (LNG) club” and has expressed its ambition for finalizing the Iran-Pakistan gas pipeline and developing the plans for the Iran-Turkey-Europe (ITE) natural gas pipeline. Cautious supervision of the post-sanction regime coupled with U.S. support for its allies’ participation in these projects can serve a number of U.S. objectives by (1) advancing American goals and commitments under international agreements regarding energy reform and climate control; (2) facilitating Iran’s transition toward friendly trade on the global stage; and (3) assisting the goals of energy security for U.S. allies by reducing Russia’s influence in the region.

Implementing a broad policy of economic reintegration for Iran through direct involvement by the U.S. government remains challenging because of the requirement for public and legislative support. Obtaining congressional approval for broad reforms in this area is still unlikely until Iran has shown true progress and firm commitment in implementing the agreement. However, more feasible short-term strategies for promoting economic reintegration can still be adopted.

Iran is the world’s top holder of gas reserves with 33.8 trillion cubic meters, and it has a high success rate of natural gas explorations, estimated to be at around 79% compared to the world average of 30%, rendering the country a uniquely attractive destination for European and American companies. Iran’s natural gas industry was negatively affected by American and European sanctions, but Iran has recently expressed a strong willingness to return to the international export arena. Traded gas is expected to expand globally by 30% by 2025, and the European Commission has suggested that Iran’s large gas and oil reserve can strengthen Europe’s energy security. In line with this trend, comes the timely affirmation that Iran has seized this opportunity in increasing its gas production to 5 billion cubic meters in the first five months of the current fiscal year.

International climate change agreements envision a healthy role for natural gas as one of the primary fuels in combating climate change and compliance with recent agreements including the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), known as COP21 or the Paris Agreement, requires favorable natural gas policies. Despite the current administration’s decision to withdraw from the agreement, senior officials have stressed the Administration’s willingness to support India and China’s role in combating climate change, including transition from coal to more efficient forms of energy. China and India have shown cooperation in this transition, and the International Energy Agency has projected that growth in natural gas demand will be mainly driven by China and the Middle East, attesting to the viability of natural gas projects in the region. Given these countries persistent reliance on the dirtiest forms of energy such as wood and coal, support for this project advances a sober idea purposed by energy scientists such as Vaclav Smil: Global environmental goals can most realistically be achieved through a system where every country moves one step up on the energy trade, with advanced economies switching to renewable energies, such as nuclear, and countries like Iran and China trading the least environmentally friendly energy sources like coal for cleaner forms of fossil energy. North Korea continues to be one of China’s main trade partners in coal, and supporting China’s transition to natural gas will inevitably lead to more cooperation with the Trump administration’s goal to isolate North Korea.

Aware of the opportunities in this growing market, Iran has expressed its intention to join the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor which links the largest natural gas-producing region in western China with the Gwadar deep-sea port in Balochistan, running through Pakistan. Iran’s involvement will include connecting the pipeline to the Chabahar port in the Gulf region. Both the international sanctions imposed on Iran and Pakistan’s financial deficiencies originally delayed the progress of the Iran-Pakistan pipeline, but, today, China’s initiative in financing parts of the project have brought the project closer to reality. Nonetheless, the Department of State’s unclear stance on how the remaining Iran sanctions and the possibility of a “snap back” in sanctions can affect the project has added to Pakistan’s hesitant approach in resuming the project. India also receives 70% of its electricity from coal and has previously shown interest in extending the pipeline to reach the country. India’s desire to join the project provides an opportunity for increasing peace and cooperation between India and Pakistan by relying on the economic interdependency that will result from the contract.

At the same time, Iran and Turkey have already laid the initial steps for an Iran-Turkey-Europe (ITE) pipeline, connecting Iran to Turkey’s border with Greece. In 2013, the Turkish government approved the urgent expropriation of land along the proposed route for the pipeline. Among the countries that rely on gas imports from Iran, Turkey is assessed to face the most significant supply challenge, should its trade with Iran be restricted. Both technical problems inside Turkey and spikes in domestic demand for gas inside Iran have recently caused instances of shortfall in gas exports to Turkey. This problem then reverberates to Greece, as Turkey attempts to remedy its shortage in gas by limiting its re-exports to Greece. Both countries, therefore, have more incentive to facilitate their trade with Iran, as their demand is projected to grow.

Additionally, other key American allies such as South Korea are likely to reap some of the economic benefits that might arise from a growing gas market in Iran. Qatar, another American ally in the region, is collaborating with Iran in developing 24 phases of one of the largest gas fields in the world, the South Pars, which will be fully operational in 2018. Currently 90% of Iran’s natural gas exports go to Turkey, shaping the incentives for the ITE pipeline that will extend this relationship to Europe. European demand for gas is projected to increase by 15-20% by 2025, and introducing an alternative market can reduce the European allies’ reliance on the Russian market. The geopolitical benefits of such transition for America is highlighted by the evident reluctance among European allies to enforce stringent sanctions on Russia for its recent recalcitrant behavior in Ukraine; a pattern that has its roots in the allies’ concern for Russia’s perceptible power in influencing the European energy market. If Russian provocations in Eastern Europe persist, the most likely victims are countries such as Belarus that have shown willingness to pivot towards the EU coalition but are partially tied back because of their energy ties to Russia. Belarus, as an example, is estimated to owe close to 15% of its GDP to trade transit activities linked to Russia’s transport of oil and gas to other European countries.

Iran has already taken affirmative steps in implementing domestic reform to its energy sector subsequent to the lifting of the sanctions. The country recently introduced a new model petroleum contract that is intended to encourage more foreign investment in its energy sector by removing barriers for reimbursing foreign investors. Iran also agreed to amend its Gas Sale and Purchase Agreement (GSPA) with Pakistan to give the country more time to finalize the Iran-Pakistan pipeline project. Policies from the White House can reinforce these positive steps at normalizing trade security for American allies in the region. A U.S. policy favorable to finalizing these projects can also provide a platform for expanding negotiations with Iran beyond the nuclear issue.

The Administration has a number of different pathways available. First, the Department of State’s involvement can include an active engagement from high level diplomats and special envoys for international energy affairs in the Bureau of Energy Resources (ENR) to sensitize other regional powers such as Pakistan, India, and Turkey to the diplomatic benefits of proceeding with their prospective plans for partnership with Iran. The Bureau’s recent successful attempt as an intermediary in initiating and concluding the gas trade partnership between Israel and Jordan is surely a laudable precedent. The State Department’s success in brokering the gas trade between Israel and Jordan, despite the political pressure from inside Jordan to refuse the deal, attests to the ENR’s influential role in using diplomatic channels to bypass regional hostilities. Similarly, the Department of Energy’s role can be utilized through coordination of its USAID program and increasing support for private sector partnerships in Pakistan that can be tailored to encourage investments in natural gas and enhance the expertise and infrastructure in this field.

Finally, a more direct involvement by the Administration can entail consideration of relaxing specific sanctions pertaining to the exchange of advanced technology. LNG requires access to advanced technology that is only available from limited number of European and American companies. The Iran Sanctions Act which shaped the core of U.S. sanctions aimed at Iran’s energy sector originally did not cover investment in Iran’s development of its LNG program. The Comprehensive Iran Sanctions, Accountability, and Divestment Act of 2010 (CISADA) later amended this language to sanction investments in Iran LNG’s sector. In addition, other legal authorities sanctioning exportation of goods and technologies remain in place pursuant to the Iranian Transactions and Sanctions Regulations (ITSR). The Administration preserves a waiver power under CISADA, and the Department of Treasury controls a general licensing program for providing exemptions from ITSR. In this context, the U.S. Treasury Department’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (“OFAC”) can review its policy toward granting export licenses to U.S. persons and foreign subsidiaries of U.S. companies that seek joint ventures or transfer of technology to Iran limited to the specific field of LNG exploration. OFAC most recently exercised this power to relax restrictions on exportation of commercial passenger aircrafts and related services to Iran.

Finally, other attempts by the Treasury Department to further clarify the exact bounds of the Administration’s enforcement policy with regard to the remaining Iran sanctions can introduce more predictability and reduce uncertainty for foreign companies attracted to investment opportunities in Iran’s gas market. Iranian foreign minister Mohammad Javad Zarif has noted that “precise assurances” from the U.S. government to the European banks about engagement with Iran can ease some of the remaining uncertainty about Iran-EU joint ventures. As the most marvelous chapters in the history of American diplomacy, such as the Marshall plan, suggest, often the greatest achievements lie in the courage to envision the opportunities that can be unlocked through international economic partnerships. In an unlikely region and among unlikely partners, another opportunity for a grand American diplomatic bargain is waiting to be seized.

About the author:

*Kia Rahnama is a student of international law at George Washington University. He frequently writes about politics and cinema and can be found on Twitter at @KRahnama

Source:

This article was published by Modern Diplomacy