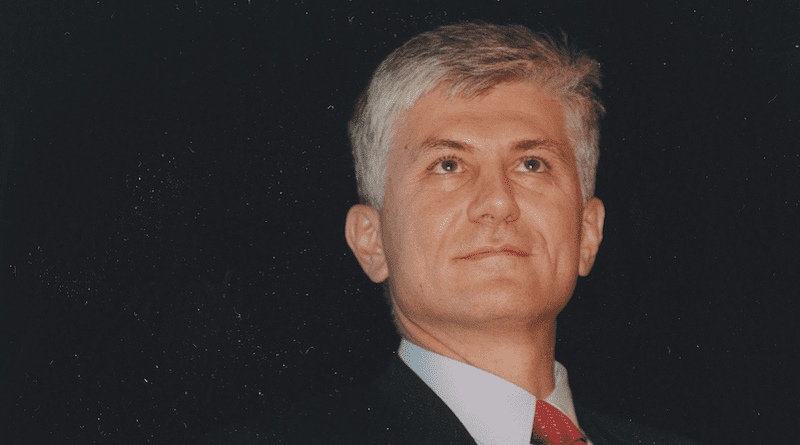

How Serbia’s Rotten System Enabled PM Zoran Djindjic’s Killers – Analysis

Twenty years ago, state security service operatives conspired with gangsters and policemen to assassinate Serbia’s liberal-democratic Prime Minister Zoran Djindjic – and court documents show how a corrupted law enforcement system made it possible.

By Milica Stojanovic

On February 19, 2003, three men met in a café near the famous Atelje 212 Theatre in Belgrade city centre.

One of them was 33-year-old Dejan ‘Bagzi’ Milenkovic, a member of the Zemun Clan, a gang led by Dusan Spasojevic, who was a notorious criminal at the time.

The second was Zoran Vukojevic, a former policeman who was working as a security guard at gang leader Spasojevic’s house.

The third was Branislav Bezarevic, who worked for the Security Information Agency, BIA, Serbia’s national intelligence agency, and was Vukojevic’s friend from police school.

Vukojevic arranged the meeting. “During that conversation, Bagzi asked him [Bezarevic] if he would like to give information about the movements of the prime minister,” he recalled later in testimony at the District Court in Belgrade.

“[Bezarevic] looked at me, I told him to speak freely. And they agreed there that he wants to give information.”

At the meeting, it was agreed that the Zemun Clan would pay Bezarevic 50,000 euros for information about Prime Minister Zoran Djindjic’s movements.

“Branko asked why do you need that information, and Bagzi said, ‘We’ll hit him, but what do you care? That’s of no interest to you,” Vukojevic said.

“That’s when I learned for the first time – later in that conversation with Dusan, he said that they had decided to kill Djindjic.”

Zoran Djindjic was the first democratic, post-communist prime minister of Serbia, and had been one of leaders of the political movement that brought down Serbian strongman Slobodan Milosevic in October 2000. He became prime minister in January 2001.

He inherited a country that was devastated by sanctions and organised crime and at the same time had to face up to the challenge of prosecuting war criminals and gangsters.

His brief time in office was fraught with threats and crises. By the time Bezarevic met Vukojevic and Milenkovic in February 2003, Djindjic had already politically survived a mutiny by the State Security Service’s Special Operations Unit, the JSO, and had physically survived an assassination attempt in January the same year.

Two days after the meeting, there was another failed attempt to kill him. Then, on March 12, Zvezdan Jovanovic, a JSO member, shot and killed Djindjic in broad daylight at the entrance to the Serbian government building. The murder was a joint operation by the JSO and the Zemun Clan – state security operatives and violent gangsters working together.

Twenty years on, an examination of documents from the subsequent court cases shows how the entire police, state security and prosecutorial system had become corrupted by criminal involvement under the Milosevic regime, and had clearly ceased to uphold the rule of law long before Djindjic became prime minister. In such an environment, the court records show, it wasn’t so difficult to organise the assassination of a prime minister.

“It is merely an indication of the deep connection between the executive power, the security sector and organised crime, which experienced its metastasis during the rule of Slobodan Milosevic in the nineties,” said Filip Ejdus, an associate professor at Belgrade’s Faculty of Political Science.

‘The criminals were working for Milosevic’

When Djindjic was shot, he was going into the government building to meet Sinisa Nikolic, his adviser who at that time was head of the Belgrade Land Development Public Agency, and was waiting in the prime minister’s office. Nikolic and Djindjic had worked together since 1997, when Nikolic, a Belgrade lawyer, become chief of staff for Djindjic after he became mayor of Belgrade.

After Djindjic’s short mayoral mandate, he continued working as president of the Democratic Party in opposition to the Milosevic regime, and Nikolic continued to be his chief of staff.

“That opposition period was very intense, stormy and problematic for the safety of him and his environment and for us personally who worked with him,” Nikolic told BIRN ahead of the 20th anniversary of his colleague and friend’s assassination.

“It was a public secret then that criminals and the underworld were working for Milosevic and that they were ready to do whatever he said,” he added.

One of Nikolic’s tasks was to maintain contact with a senior official at the State Security Service, who “risked his head” by sometimes passing information to them, which Nikolic said had ensured Djindjic’s survival up to that point.

They then received information that the Democratic Party headquarters in Belgrade had been bugged.

“Zoran introduced the practice that when he talks to me or a close associate about something that shouldn’t be overheard, he calls us to the toilets and turns on the tap, and then we use that stream as cover to talk so that they don’t hear us,” Nikolic recalled.

A serious warning was delivered in the spring of 1999, during the NATO bombing of Yugoslavia, when there was a harsh campaign in the Serbian media against internal “traitors” – Djindjic being the main one. The State Security Service contact told Nikolic that Djindjic should leave the country.

“I come and pass it on to Zoran, under the faucet, he says it’s confirmation, I already have one such piece of information, so that’s it,” Nikolic recalled.

Djindjic went to Montenegro, but not long after that, Nikolic got another nudge.

“One day I get a call from a friend from State Security and he tells me, ‘Call your friend and tell him not to jog anymore, it’s not healthy,’” Nikolic said.

He went to a public telephone booth he knew was safe from wiretapping, called a previously agreed number in Montenegro and asked for Djindjic.

“Zoran answers, out of breath. I say, ‘It’s not healthy to run.’ On the other side – [there was] silence, he realised [what had happened] immediately,” Nikolic said. Serbian State Security had located him; he remained inside to avoid being attacked until he thought it was safe to return to Serbia.

After the NATO bombing was over in June 1999, a new period of political turbulence started, as the Serbian opposition attempted to step up its campaign to overthrow an increasingly autocratic Milosevic.

This finally happened in autumn 2000, when opposition leader Vojislav Kostunica beat Milosevic in snap Yugoslav federal presidential elections. Serbian parliamentary elections were in December and in January 2001, Djindjic become premier.

Nikolic explained that he and Djindjic continued to work together, although in a different format, and saw each other two or three times a week.

In autumn 2002, Nikolic went to Djindjic’s residence to give him a message. He started talking, but Djindjic interrupted him.

“He says ‘stop’, takes me to the kitchen and turns on the tap, stands by the tap and says, ‘What did they tell you?’” Nikolic recalled.

“I ask him, indicating [the tap], I ask if it is necessary [to turn it on], and he says, ‘Yes, yes, yes, it’s necessary.’ And then I realise that he, the prime minister, is under surveillance… I realise that there is a problem.”

‘No one dared look us in the face’

Back in 1995, eight years before his meeting with Milenkovic and Bezarevic, Zoran Vukojevic was a police officer in the Belgrade municipality of Zemun. He arrested a then little-known criminal called Dusan Spasojevic for possessing an unregistered weapon.

Vukojevic allowed Spasojevic to go free; afterwards Spasojevic gave him information about the whereabouts of some two kilograms of heroin. In 1997, Spasojevic was the best man at Vukojevic’s wedding.

Vukojevic meanwhile left the police and started working as a private security guard. In 2000, he was engaged as chief of security at Spasojevic’s house in Zemun, which was the clan’s headquarters. He kept his police ID card.

By that time, Spasojevic and his deputy Mile ‘Kum’ Lukovic were working closely with Milorad ‘Legija’ Ulemek, commander of the JSO. This amalgam of street brutality and state power led to the Zemun Clan becoming practically the strongest force in the country.

“No one even dared to approach us. The police were running away from us… No one dared look us in the face,” Vukojevic told the District Court in Belgrade.

The fact that Legija then made an agreement with Djindjic that the JSO would not intervene in the protests that toppled Milosevic in October 2000 further boosted the unit’s status as a major force in the country. Djindjic’s government also reacted mildly when the JSO staged a mutiny in November 2001.

According to Ejdus, after 2000, State Security and the JSO were “reserved domain”, that is, a part of the executive power outside the control of representatives of the democratically elected government.

“This department or its parts, in addition to protecting their own corporate interests, were also instrumentalised by the mafia and probably by representatives of the previous government,” Ejdus told BIRN.

This became the case, he said, particularly after Milorad Bracanovic, “the man who connected the JSO and the Zemun clan,” was named as State Security deputy chief in November 2001, after the mutiny.

“We can assume that there was also a connection with politics, but as we know, the political background of the assassination of Prime Minister Djindjic remained unexplained.”

But by 2002, Djindjic’s government had started trying to fight organised crime and preparing to prosecute gang members, and was searching for inside informers. They founded one in Ljubisa ‘Cume’ Buha, Spasojevic’s fellow gang member.

Spasojevic then decided to kill Buha. Vukojevic knew this and talked about it with his friend from the police, Bezarevic, asking him for information about Buha’s movements. “He gave us that information,” Vukojevic told the court later.

The day after meeting Milenkovic on February 19, 2003, Vukojevic and Bezarevic met again. Bezarevic brought information that Djindjic was going to travel to Banja Luka in Bosnia the next day.

“He explained to me which car [from Djindjic’s escort] was going and which way,” Milenkovic later said.

Vukojevic said Bezarevic found a despatch about Djindjic’s planned travels at the Serbian Interior Ministry Security Institute.

“And he also said that they have some monitors at that centre, and those monitors are directed towards the prime minister’s residence, and then he watched [Djindjic’s] movements from there,” Vukojevic said.

Vukojevic passed this information on to Spasojevic and the next day, the gang tried to kill Djindjic on the Belgrade-Zagreb highway, but failed.

Policemen complicit in gang crimes

Directly after Djindjic’s assassination, a state of emergency was imposed and the police launched a large-scale crackdown. During Operation Sabre, a total of 11,665 people were held, and 3,946 of them were ultimately charged.

There were two major trials of Zemun Clan and some JSO members: one for murdering Djindjic and the other one for 17 other murders, one attempted murder, four kidnappings and other criminal acts. Twelve people were jailed in 2009 for Djindjic’s assassination.

During the trials, it was established that Dusan Spasojevic had another best man, Slobodan Pazin, an inspector in the Belgrade Police who was also aiding the Zemun Clan.

Pazin, together with 32 other people, was convicted in the second case. According to the verdict, Pazin “knowingly failed to report criminal acts that he learned about in the course of his duties”.

The verdict said that Pazin knew who killed six of the gang’s victims between 2000 and 2002 but “failed to report the perpetrators of these crimes” committed by the Zemun Clan and Legija. Pazin was sentenced to seven years and five months in prison.

Another policeman who was helping the Zemun Clan in return for money was Toni Gavric. He got information from a State Security employee about the whereabouts of the informer Ljubisa Buha, and gave it to Dejan Milenkovic, “who gave him 700 euros for that information”, the verdict said.

The gang also got information about Buha’s movements from a prosecutor, Milan Sarajlic, according to Milenkovic, who later became a witness in the case. Sarajlic was jailed for three years in a separate case.

Ahead of the 20th anniversary of Djindjic’s killing, his friend Nikolic said he still thinks there was a chance that the prime minister could have been saved, but it would have taken more to protect him than just his bodyguards, one of whom was also wounded during the shooting on March 12, 2003.

“I don’t even think that maybe he, as someone who was with [Djindjic], could have saved his life if the intelligence circle did not save his life, as it didn’t inform them that a sniper might be waiting at the window that day,” Nikolic said.

“And later we find out that everyone who was involved in some kind of security knew that they were preparing to hunt him down.”

What happened to the conspirators?

Zoran Vukojevic became a witness for the prosecution and testified about the Zemun Clan’s crimes. He was killed in 2006 before the end of the trial.

Dejan Milenkovic also became a witness for the prosecution. He is still alive and has testified in a number of other organised crime cases dating to the 1990s.

Branislav Bezarevic was convicted of involvement in Djindjic’s murder and is now serving his sentence.

Dusan Spasojevic was killed by police as they tried to arrest him in 2003.

Milorad ‘Legija’ Ulemek, the commander of the JSO and mastermind of the Djindjic killing, is serving his sentence for this and other crimes.

Besides Ulemek and Bezarevic, also convicted were: Zvezdan Jovanovic, the gunman, Aleksandar Simovic, Ninoslav ‘Nino’ Konstatinovic, Vladimir ‘Vlada Budala’ Milisavljevic, Sretko ‘Zver’ Kalinic, Milos Simovic, Milan ‘Jure’ Jurisic, Dusan Krsmanovic, Sasa Pejakovic and Zeljko ‘Zmigi’ Tojaga.

Milisavljevic is in jail in Spain, Jurisic and Konstatinovic were killed. Tojaga, Pejakovic and Krsmanovic have since been granted early release.