Periodic Review Board Decides Yemeni At Guantánamo Still Poses A Threat 14 Years After Capture – OpEd

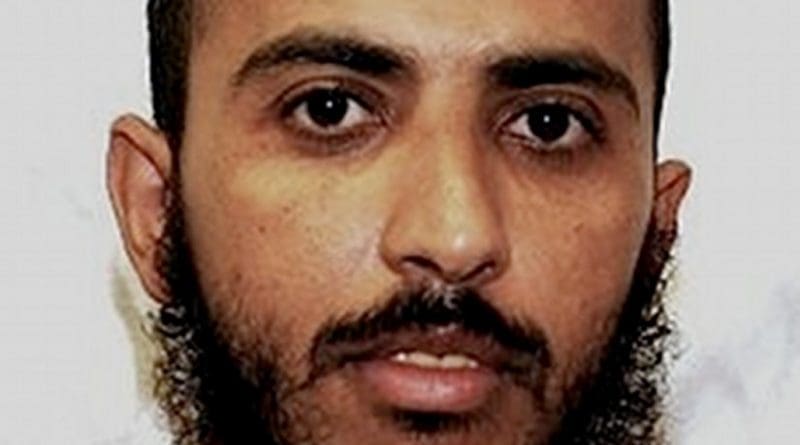

In its latest “Unclassified Summary of Final Determination,” a Periodic Review Board at Guantánamo — a high-level review process involving representatives of of the Departments of State, Defense, Justice and Homeland Security, as well as the office of the Director of National Intelligence and the Office of the Joint Chiefs of Staff — decided, by consensus, that “continued law of war detention” of Suhayl Abdul Anam al-Sharabi (aka Zohair al-Shorabi, ISN 569), a 38- or 39-year old Yemeni, “remains necessary to protect against a continuing significant threat to the security of the United States.”

The decision, dated March 31, 2016, and following on from his PRB on March 1, is not entirely surprising for two reasons — firstly, because of allegations levelled against al-Sharabi, suggesting that he was actually involved with terrorists, unlike the majority of prisoners held at Guantánamo since the prison opened in January 2002, and, coupled with this, a failure on his part to show contrition, and to come up with a plan for his future.

In its determination, the board stated that its members had “considered the detainee’s past involvement with terrorist activities to include contacts with high-level al Qaeda figures, living with two of the 9/11 hijackers in Malaysia, and possible participation in KSM’s plot to conduct 9/11-style attacks in Southeast Asia. The Board noted the detainee’s refusal to admit the extent of his past activities, as well as his evasive and implausible responses to basic questions. Further, the Board considered the detainee’s defiant behavior while in detention, which has only recently changed to be more compliant, and the detainee’s lack of a credible plan for the future.”

Regarding the alleged plot by KSM — a reference to the “high-value detainee” and alleged 9/11 mastermind Khalid Sheikh Mohammed — I have never found it plausible that any other plots were seriously underway to follow up on 9/11, and I think it is important that, institutionally, no evidence has been found of any follow-up plot, which would otherwise provide comfort to those who try to defend the horrors of the “war on terror” — extraordinary rendition, torture and indefinite imprisonment without charge or trial.

As Lawrence Wilkerson, the former chief of staff to Secretary of State Colin Powell, told me during an interview in 2009, when discussing the Bush administration’s expectation of another attack, “I thought before that it had persisted all the way through 2002, but I’m convinced now, from talking to hundreds of people, literally, that that’s not the case, that their fear of another attack subsided rather rapidly after their attention turned to Iraq, and after Tommy Franks, in late November as I recall, was directed to begin planning for Iraq and to take his focus off Afghanistan.”

Nevertheless, al-Sharabi’s connection with Al-Qaeda — whether a plot existed or not — cannot be brushed aside easily, and, to be overcome, would require a commitment on his part to engage with the review board that was evidently not forthcoming, hence his “refusal to admit the extent of his past activities,” his “evasive and implausible responses to basic questions” (which is clearly no way to behave before what is, essentially, a parole board), and his “lack of a credible plan for the future,” which is also no way to impress one’s captors if the possibility of release exists.

It clearly did not help that al-Sharabi chose to undertake his PRB without the support of his lawyers, at Kilmer, Lane & Newman, LLP, in Denver, Colorado, and it is to be hoped that he will engage more thoroughly with the process when his case is reviewed again.

As the board members described it, “The Board looks forward to reviewing the detainee’s file in six months and hopes to see continued compliance in detention, continued participation in educational opportunities, a more thoughtful articulation regarding handling the challenges of resettlement, and candor with the Board.”

With the review board’s decision in al-Sharabi’s case, 20 men have now been recommended for release , while six have had their ongoing imprisonment recommended (see our detailed Periodic Review Board list for the full story). This is still a success rate for the prisoners of 77%, and a damning indictment of the government’s claims, made by President Obama’s high-level, inter-agency Guantánamo Review Task Force back in 2010, that the majority of the men who were later put forwards for PRBs were “too dangerous to release,” even though the task force conceded that insufficient evidence existed to put them on trial. Of the 26 men in whose cases PRB decisions have been taken, 24 have been from the “too dangerous to release” camp, and 19 of those men have been recommended for release.

48 men were initially designated as being “too dangerous to release,” although two died before the PRBs began. By that time, however, 25 others had been added, who had initially been recommended for trials until a number of rulings by the appeals court in Washington, D.C. overturned some of the few convictions achieved in Guantánamo’s military commission trial system, on the embarrassing basis that the war crimes for which the men had been convicted had been invented by Congress.

Decisions have been taken in the cases of just two of the 25 — al-Sharabi and Tariq al-Sawah, an Egyptian whose PRB recommended his release last year, and who was freed in Bosnia in January. Two others have had reviews and are awaiting the results, and others are scheduled to have reviews in the coming months. 35 men in total are awaiting reviews, which, the administration has promised, will take place before President Obama leaves office.

It is likely that a greater proportion of these men will have their ongoing imprisonment recommended, unlike those in the “too dangerous to release” category, which, on reflection, must be regarded by the government as an ill-advised definition.

However, it ought to be troubling, to some extent, that the US continues to defend the ongoing imprisonment of men like Suhayl al-Sharabi, who was involved with Al-Qaeda when he was in his early 20s, and against whom no evidence exists that he was involved in any concrete plot, or contributed in any way to any efforts that killed a single American. Set against these concerns is the reality that he has further opportunities to address the review board, to try to persuade them to approve his release, but in the end the government ought to be defending prisoners’ ongoing imprisonment either because it is putting them on trial — a situation that only applies to ten of the 89 men still held at Guantánamo — or because it maintains that it has the right to hold combatants until the end of hostilities.

The PRBs are neither, and, while they are a useful way of chipping away at decisions taken back in 2010 that were clearly far too cautious, that does not eliminate the fundamental problem that a parole-type system has been set up to review what are supposed to be, for the most part, wartime detentions, and that prisoners detained according to the laws of war ought to be freed at the end of hostilities, and not required to plead for their release via government review boards.

The government has been unwilling to accept that its “war on terror” has an end date, and it is unsettling that there have not been more robust legal challenges to the ongoing imprisonment of men for longer than the Vietnam War, or the First and Second World Wars combined.

If Guantánamo is to be closed, as we still dare to hope it might be by the time President Obama leaves office, the men facing trials, and those recommended for ongoing imprisonment without trials, will need to be moved to a facility or facilities on the US mainland. When — if — this happens, those facing trials should be tried in federal court, and as few as possible of the rest should be designated for ongoing imprisonment without trial. If any evidence exists to justify their detention, they too should be put on trial.

Here at “Close Guantánamo,” the only comfort we can take from the intention to move men from Guantánamo to the US mainland for ongoing imprisonment without charge or trial is the fact that they will be able to make new legal challenges regarding the basis of their ongoing imprisonment, which, we believe, will challenge the administration more effectively than was possible when they were at Guantánamo.

As “Close Guantánamo” co-founder Tom Wilner has explained, “If the detainees are brought to the United States, the government loses its prime argument for denying them constitutional rights. The imprisonment of anyone without charge or trial on the US mainland is radically at odds with any concept of constitutional due process. Bringing them to the United States means that they would almost certainly have full constitutional rights and the ability to effectively challenge their detentions in court. They would then no longer be dependent solely on the largesse of the Obama administration, or whatever administration happens to follow it, but could gain relief through the courts.”

I wrote the above article for the “Close Guantánamo” website, which I established in January 2012, on the 10th anniversary of the opening of Guantánamo, with the US attorney Tom Wilner. Please join us — just an email address is required to be counted amongst those opposed to the ongoing existence of Guantánamo, and to receive updates of our activities by email.