Prof. Dr. Steve H. Hanke On Albania: ‘A Necessary Condition For Corruption Is Government’ – Interview

By Peter Tase

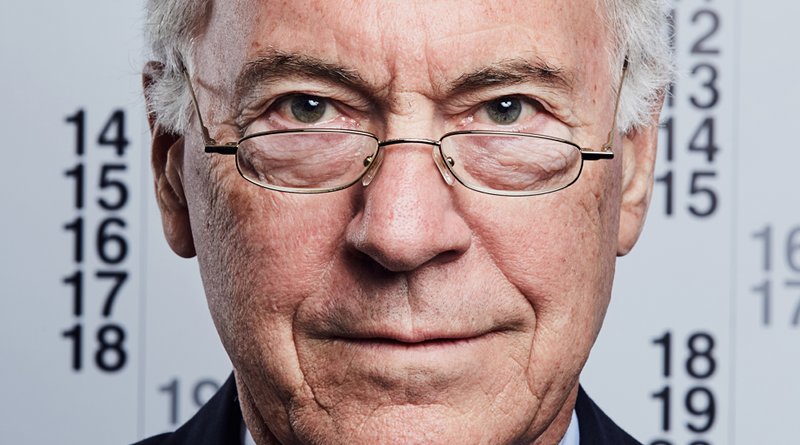

Steve Hanke is a Professor of Applied Economics at the Johns Hopkins University, the world’s expert on measuring and stopping hyperinflations, former member of Ronald Reagan’s Council of Economic Advisers where he was in charge of President Reagan’s privatization programs, and an adviser to Presidents in Europe, Asia, and Latin America, including Petar Stoyanov in Bulgaria (1997-2002), and Milo Djukanovic in Montenegro (1999-2003). He was also the Special Advisor on Currency Reform to Albania’s Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of the Economy Gramoz Pashko (1991-1992). He played an important role in establishing new currency regimes in Argentina, Estonia, Bulgaria, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Ecuador, Lithuania, and Montenegro. In 1995, he was President of Toronto Trust Argentina in Buenos Aires when it was the world’s best performing fund. In 1998, he was ranked as one of the Twenty-Five Most Influential People in the World by World Trade Magazine. At present, Prof. Hanke is ranked 5th on Focus Economics’ list of the world’s Top Economic Influencers to Follow.

Interview Questions and Answers

Q: How would you describe the current state of Albania?

Hanke: Albania continues to be dragged down by its history. After 46 years of communist rule, Albania’s weak democratic institutions have led to rampant political corruption. Edi Rama became prime minister in 2013, and his Socialist Party won a parliamentary majority in 2017. Albania’s accession to the European Union has stalled in the absence of additional reforms to fight corruption and improve the rule of law. Weak democratic institutions are the reason why Albania performed poorly in the Rule of Law and the Legal System and Property Rights category in Cato Institute’s Human Freedom Index. Albania scored a poor 5.1 out of 10, with 10 being “most free” in Legal System and Property Rights and a 5.3 out of 10 in Rule of Law. It’s no surprise that Albania scored a despicable 2.5 out of 10 for Judicial Independence.

However, the Albanian government has adopted a number of measures to reduce political corruption such as restricting the immunity of high-level public officials, politicians, and judges. In addition, Albania passed constitutional amendments reforming the judicial system in order to strengthen the rule of law in July 2016. However, these measures have not been proven to be effective, and political corruption continues to be an obstacle for Albania’s candidature for EU membership. According to the World Justice Project Rule of Law Index 2019, Albania ranks 103rd out of 126 countries for Absence of Corruption. Additionally, according to Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) 2019, Albania ranks 106th out of 180 countries. Albania’s CPI score has declined steadily since 2016. And, it will probably continue to do so if substantial changes are not made.

Q: What is Albania’s relationship to the European Union?

Hanke: In April 2018, the European Commission recommended to open accession negotiations with Albania and North Macedonia. The EU’s executive said on March 2nd that Albania and North Macedonia have done enough to merit starting negotiations to join the European Union. In the Commission reports on progress made by Albania and North Macedonia, the update outlines “progress in the implementation of justice reform and the vetting process of judges and prosecutors, on the track record demonstrated in the fight against corruption and organized crime.”

Although this might be the case, Albania’s political system remains divided. This hinders the implementation of sound reforms. As a result, its economic, social, and political prosperity lag behind. One would argue that Albania is not in the proper state to be accepted into European Union membership. For example, on March 2nd, thousands of opposition supporters denounced Albania’s government at a protest rally, deepening the divide between the president, Ilir Meta, and the socialist administration. Public administration in Albania is affected by inefficiency, incompetence, and widespread corruption. Therefore, the political crisis has not come as a surprise. These instances of Albania’s corruption are reflected by the World Bank’s Worldwide Governance Indicators. In all six dimensions of governance, Albania’s rankings are relatively low. The most striking of these are:

- Control of Corruption: Albania is 136th out of 209 countries

- Rule of Law: Albania is 127th out of 209 countries

- Government Effectiveness: Albania is 138th out of 209 countries

Albania’s rankings in these crucial dimensions rank much lower than any European Union member state. For example, the lowest ranking of an EU member state for Control of Corruption is Bulgaria at 103rd, for Rule of Law is Bulgaria at 98th, and for Government Effectiveness it’s Romania at 119th. Thus, although the European Union has told Albania that its reforms must remain a top priority if it wants to join the bloc and that its judiciary should be able to fight corruption and crime, these indices show that little progress has been made. Albania is ranked worse than Bulgaria, which should raise some flags for the European Union.

Therefore, Albania must undergo substantial transformation to continue on its European path. This transformation includes strengthening democracy (rule of law, justice, and fundamental rights), reforming public administration, strengthening competitiveness, and supporting free markets.

Q: How would you describe Albania’s judicial system?

Hanke: Albania continues to be sabotaged by corruption; thus, it finds itself in the most extraordinary position when it comes to the judicial system. Albania is the only country in the world which has a constitutionally enshrined body led by the United States State Department, U.S. Justice Department, and EU Commission, which vets Albania’s judiciary: The International Monitoring Operation. This justice reform package was adopted in 2016 aimed at restoring public confidence in the judiciary. As of 2019, the Fraser Institute Economic Freedom of the World 2019 report states that Albania’s worst performance was in its Legal System and Property Rights category, with a score of 5.09 out of 10 and ranked 83rd out of 162 countries. The IMO is a temporary international body mandated in Albania’s constitution which: “ (1) monitors and observes the establishment of a new vetting commission, public commissioners and appeal chamber for vetting of Albanian judges and prosecutors and (2) monitors and observes the vetting itself.” This is in line with the World Bank’s Worldwide Governance Indicator, which scores Albania 39 out of 100 for Rule of Law. This score is lower than the Europe & Central Asia Rule of Law score of 63 out of 100.

Q: What is the current state of the economy in Albania?

Hanke: Thanks to Albania’s Communist rule, it is one of the most impoverished countries in Europe. Albania has seen its economy grow, but at a moderate pace at best.Albania is now implementing a 2019-2021 reform program that would, if implemented correctly, both increase efficiency and decrease regulation in the economy. The reforms include reducing regulatory burden to businesses, liberalization of the energy market, and providing a single and transparent investment legal regime in the country.

Annual growth for 2019 remains weak and is projected to be 2.9%. This is below the 4.1% rate of growth in 2018. This year’s outlook is not bright. This is confirmed by Albanians themselves. They continue to leave the country in search of jobs. A demographic crisis is present, as people are having fewer children. In 2018, 52% of the population thought about leaving the country. More than 1.4 million Albanians have left since the end of the communist regime. Today’s population stands at 2.9 million and is declining.

Q: How would you deal with Albania’s economy corruption?

Hanke: A necessary condition for corruption is government. Corruption always and everywhere is associated with government. Just think about Albania, which by most measures is one of the most corrupt countries in Europe. You can’t name one case of Albanian corruption that doesn’t involve the government—either politicians or bureaucrats. That is because it is impossible to have corruption without government.

If government is not in the picture, there is no corruption. So, government is not only an engine for coercion and compulsion, which deprives individuals of their freedom and liberty, but it is an engine for theft and corruption. When it comes to government, I think small is beautiful. A government that accounted for 10%-15% of GDP would be just fine with me.

The best example of a clean, almost corruption-free country is Singapore. It is very relevant—specifically on corruption and in general—for Albania. If I was running the show in Albania, I would adopt what I call the Singapore Strategy. If Albania did that, it would see exceptional and tremendous growth.

Singapore gained its independence in 1965, when it was, in effect, thrown out of Malaysia. At that time, Singapore was backward and poor — a barren speck on the map in a dangerous part of the world. If that wasn’t enough, it was experiencing race riots, which came close to igniting a civil war.

But, at its founding, Singapore had a leader, Lee Kuan Yew. He had clear ideas about how to modernize the country — a strategy which I have dubbed the “Singapore Strategy.” This strategy contained the following elements:

The first element was stable money. Singapore started with a currency board system — a simple, transparent, rule‐driven monetary regime. Currency boards operate on autopilot, with automatic adjustments keeping the system in balance. Accordingly, currency boards deliver discipline to the spheres of money, banking, and fiscal affairs. For Singapore, the currency board provided stable prices and free convertibility of the Singaporean dollar, which was fully backed by foreign reserves and gold, at a fixed exchange rate. This established confidence and attracted foreign investment.

The second element was that Lee Kuan Yew ruled out passing the begging bowl. Singapore refused to accept foreign aid of any kind. This is a far cry from many developing countries, like Albania, where, when you pick up the paper, all you see are politicians and bureaucrats trying to secure foreign aid (and EU transfer payments) from someone, be it an NGO, a foreign government, or an international financial institution, like the World Bank. By contrast, signs reading “no foreign aid” were hung figuratively outside every government office in Singapore.

The third element was that Singapore strived to have first‐world, competitive private enterprises. This was accomplished via light taxation and light regulation, coupled with completely open and free trade — in short, policies that enabled Singapore to become one of the Asian Tigers.

The fourth element in the Singapore Strategy was an emphasis on personal security, public order, and the protection of private property.

The fifth, and final, element in the Singapore Strategy was a “small,” transparent government — a minimalist government that avoided complexity and “red tape.”

To execute the strategy with precision, Singapore appoints only first‐class civil servants and pays them first‐class wages. Today, for example, the Singaporean Finance Minister’s annual salary is 1.15 million euros. In exchange for these high salaries, the Singapore Strategy demands that the government runs a tight ship, with no waste or corruption. By embracing Lee Kuan Yew’s Singapore Strategy of stable money, no foreign aid, first‐world competition, law and order, and a government that is free of waste and corruption, Singapore has transformed itself from a poor, barren speck to a global financial center and one of the richest countries in the world.

Note: This interview was published in Albanian Language version, on the following newspapers:

- https://kohajone.com/profesori-i-njohur-steve-hanke-ne-shqiperi-ka-korrupsion-te-shfrenuar-ekonomia-dhe-gjyqesori-hapa-pas/

- http://www.panorama.com.al/ekonomia-gjyqesori-dhe-korrupsioni-i-shfrenuar-politik-profesori-steve-hanke-flet-per-shqiperine-dhe-kujton-shembullin-e-singaporit-ja-problemet-e-medha-qe-keni/