United Nation Issues: US Funding To UN System – Analysis

By CRS

The United States is the single largest financial contributor to the United Nations (U.N.) system. Congress has long debated the appropriate level of U.S. funding to U.N. system activities and whether U.S. contributions are used efficiently and effectively. U.S. policymakers’ perspectives on U.N. funding have varied over time. For example, the Trump Administration consistently proposed significant decreases in U.N. funding and withheld contributions to some U.N. bodies. At the same time, Congress funded most U.N. entities at higher levels than the Administration requested. The Biden Administration supports U.S. engagement with U.N. entities; the President’s FY2023 budget request proposes fully funding assessed contributions to U.N. bodies and paying selected U.S. arrears.

UN System Funding

The U.N. system comprises interconnected entities including specialized agencies, funds and programs, peacekeeping operations, and the U.N. organization itself. The U.N. Charter, ratified by the United States in 1945, requires each member state to contribute to the expenses of the organization. The system is financed by assessed and voluntary contributions from U.N. members. Assessed contributions are required dues, the payment of which is a legal obligation accepted by a country when it becomes a member. Such funding provides U.N. entities with a regular source of income to pay for staff and implement core programs. For example, the U.N. regular budget, specialized agencies, and peacekeeping operations are all financed mainly by assessed contributions. Voluntary contributions primarily finance U.N. funds and programs, such as UNICEF and the U.N. Development Program, and donor commitments may fluctuate annually. For more information on the U.N. system, see CRS In Focus IF11780, United Nations Issues: Overview of the United Nations System, by Luisa Blanchfield.

UN regular budget.

The U.N. regular budget funds the core administrative costs of the organization, including the U.N. General Assembly, Security Council, Secretariat, International Court of Justice, special political missions, and human rights entities. The regular budget is adopted by the Assembly and used to cover a two-year period; however, in 2017 the Assembly voted to change the budget cycle to a one-year period beginning in 2020. Most Assembly decisions related to the budget are adopted by consensus. When budget votes occur (which is rare) decisions are made by a two-thirds majority of members present and voting, with each country having one vote. The approved regular budget for 2022 is $3.12 billion. The Assembly determines a scale of assessments for the regular budget every three years based on a country’s capacity to pay. Most recently, the Assembly adopted assessment rates for the 2022-2024 period in December 2021. The United

States is assessed 22%, the highest of any U.N. member, followed by China (15.25%) and Japan (8.03%).

UN Specialized Agencies.

The 15 U.N. specialized agencies, which include the World Health Organization; Food and Agriculture Organization; and U.N. Educational, Scientific, and Educational Organization (UNESCO), among others, are autonomous in executive, legislative, and budgetary powers. Some agencies follow the scale of assessment for the U.N. regular budget, while others use their own formulas to determine assessments. The United States is a member of 12 of 15 U.N. specialized agencies.

UN peacekeeping funding.

There are currently 12 U.N. peacekeeping missions worldwide with over 80,000 military, police, and civilian personnel. U.N. Security Council resolutions establishing new operations specify how each mission will be funded. In most cases, the Council authorizes the General Assembly to create a discrete account for each operation funded by assessed contributions; recently, the General Assembly temporarily allowed peacekeeping funding to be pooled for increased financial flexibility due to concerns about budget shortfalls. The approved budget for the 2021-2022 peacekeeping fiscal year is $6.37 billion. The peacekeeping scale of assessments is based on modifications of the regular budget scale, with the five permanent Council members assessed at a higher level than for the regular budget. The current U.S. peacekeeping assessment is 26.94%; however, Congress has capped the U.S. contribution at 25%. China (18.68%) and Japan (8.03%) have the next highest assessment rates.

US Funding

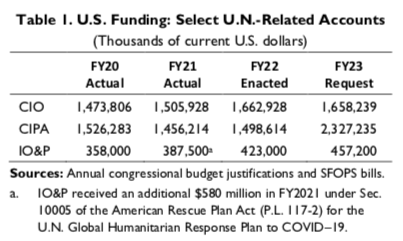

Congress has generally authorized funding to the U.N. system as part of Foreign Relations Authorization Acts, and appropriated funds through the Department of State and U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) accounts in annual Department of State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs (SFOPS) appropriations bills (Table 1). President Biden’s FY2023 budget request includes the following:

- $1.66 billion for the Contributions to International Organizations (CIO) account, which funds assessed contributions to the U.N. regular budget, U.N. specialized agencies, and other international organizations (about $4.7 million less than the FY2022 enacted amount). This includes $1.17 billion for U.N. entities, including $150 million to pay U.S. assessments to UNESCO, subject to restrictions under P.L. 101-246 and P.L. 103-236. (These laws prohibit funding to U.N. entities that accord the Palestine Liberation Organization the same standing as member states, or grant full membership as a state to any group that does not have the internationally recognized attributes of statehood. UNESCO admitted the Palestinians as a member in 2011. The United States withheld UNESCO funding from FY2012 until its withdrawal from the organization in 2018.)

- $2.33 billion for the Contributions for International Peacekeeping Activities (CIPA) account, which funds U.S. assessed contributions to most U.N. peacekeeping operations (a nearly $830 million increase over the enacted FY2022 amount of $1.5 billion, which includes funding up to the 25% cap). The request, which would fully fund U.N. peacekeeping beyond the cap, also includes $620 million to pay arrears accrued from FY2017 to FY2020 due to the 25% cap and $110.3 million to pay arrears from the 2021-2022 peacekeeping year (also due to the cap).

- $457.2 million for the International Organizations and Programs (IO&P) account, which funds mostly core voluntary contributions to U.N. funds and programs and other international organizations (about $34 million over the FY2022-enacted amount of $423 million). The FY2023 request includes $135.5 million for UNICEF and $56 million for the U.N. Population Fund.

Other U.S. Contributions.

The United States also provides voluntary contributions to U.N. entities through other SFOPS accounts. Congress generally appropriates overall funding to each of these accounts, while the executive branch determines how funds are allocated based on policy priorities and issue-specific needs. For example, USAID reports that the United States contributed about $5.87 billion to U.N. entities through global humanitarian accounts in FY2020 (most recent data available), including Migration and Refugee Assistance, International Disaster Assistance, and Food for Peace, Title II (P.L. 480). Such funding supported U.N. entities such as the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees and World Food Program. U.S funding is also provided through accounts supporting health, security, and development programs, including the Economic Support Fund and Global Health Programs accounts, among others. In FY2020, U.N-related funding from these and other accounts was about $1.1 billion.

U.S. Arrears.

The United States often accumulates arrears to the U.N. regular budget and other U.N. bodies due to differences between the U.S. and U.N. fiscal years (which affects the timing of U.S. payments), U.S. withholdings from U.N. activities, and the State Department practice of paying assessments on a deferred basis, causing some U.S. contributions to be delayed by a year. (These deferrals were originally caused by Reagan Administration withholdings to U.N. bodies in the 1980s.) The status of arrears varies by U.N. entity; each organization has its own payment timeline and system for defining and tracking arrears.

Selected Policy Issues

UN regular budget assessment.

Over the years, policymakers have expressed concern that current regular budget assessments levels result in the United States providing the bulk of funding while having minimal influence on the budget process. Some have called for increased transparency in the process for determining the scale of assessments. Conversely, others contend that the current assessment level is roughly equivalent to the U.S. share of world gross national income. They argue that it reflects U.S. commitment to the United Nations, affirms U.S. leadership, leverages funding from other countries, and helps the United States achieve its goals in U.N. fora.

US peacekeeping assessment cap.

In 1995, due to concerns that the U.S. peacekeeping assessment level was too high (over 30%), Congress set a limit of 25% on the funds authorized after FY1995. Between FY2001 and FY2016, Congress enacted legislation to raise the cap temporarily so that U.S. contributions were closer to U.N. assessment levels. It did not enact a cap adjustment for FY2017 through FY2019 and returned to 25%. As a result, the United States accumulated about $920 million in cap- related arrears from FY2017 to FY2020.

Executive branch role.

Congress does not specifically appropriate funding to many U.N. bodies. Instead, it often appropriates lump-sum amounts to U.N.-related accounts. As a result, the executive branch has some leeway to determine how funds are allocated, often with little or no congressional consultation. Some experts and policymakers are concerned that Administrations may not fund U.N. entities as Congress intended. They suggest that Congress could legislate funding levels for specific U.N. entities or activities. At the same time, others maintain that this approach deviates from long-standing (and largely bipartisan) practices intended to provide the executive branch with flexibility to respond to unpredictable circumstances (e.g. conflict, humanitarian, or health crises).

US funding and UN reform.

Congress has attempted to influence the United Nations by enacting legislation linking U.S. funding to specific U.N. reform benchmarks or activities. For example, it has withheld or conditioned funding to UNESCO, the Human Rights Council and U.N. activities related to the Palestinians. It has also limited U.S. payments to assessed budgets (e.g., the 25% peacekeeping cap). From FY2014 through FY2020, SFOPS bills linked U.S. funding to U.N. whistleblower protection policies. Some Members oppose such actions due to concerns that they may interfere with U.S. influence and standing in U.N. fora. Others maintain that the United States should use its position as the largest financial contributor to push for reform, in some cases by withholding U.S. funding.

*About the author: Luisa Blanchfield, Specialist in International Relations

Source: This article was published by CRS (PDF)

It is 2022, and netizens must ask themselves what is the role of the UN? It is certainly not a world government. It appears to be a world forum, but a forum to achieve what purpose? Apart from its specialist programs such as WHO, UNESCO and UNICEF, in outcome terms what does it actually achieve?