Back To The USSR? Memory Wars In The South Caucasus – OpEd

By IWPR

By Alaiza Pashkevich

Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelensky declared May 9 Europe Day, delivering a symbolic retort to Russia’s Victory Day parade, which commemorates the Soviet Union’s military victory over Nazi Germany in 1945.

The memory of World War II, or the Great Patriotic War as Russia calls it, has a cult-like status in Russia. Victory Day is meant to laud military valour and moral integrity, considered core to the country’s identity. Over the decades, the Kremlin has co-opted and instrumentalised the powerful memory of Soviet heroism and victimhood – some 20 million Soviet citizens are estimated to have died in WWII – to legitimise its rule.

In 2005, Russian President Vladimir Putin famously described the USSR’s collapse as “an absolutely obvious tragedy that caused broken family and economic connections”. Under the premise of “protecting” its people and drawing apparent parallels with fighting Nazism in WWII, on February 24 2022, Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

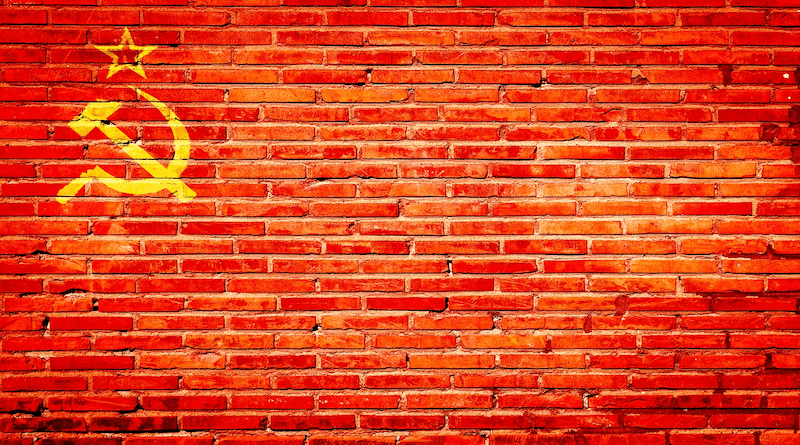

The war has unfolded beyond the military battlefields. The Kremlin’s narratives have actively manipulated history to promote what memory studies defines as “misremembering” the past. The aim is to strengthen in people’s minds the link between Joseph Stalin’s strong leadership and Putin’s aggressive rhetoric.

The Russian Federation’s citizens are not the only targets. In 2022, over half of the Armenian population (58 per cent) felt sorry about the collapse of the USSR, while 56 per cent of Russians fully or partly agreed with the statement “Stalin was a great leader”. In Georgia, Stalin’s birthplace, the share is smaller (38 per cent), but one third still has good memories about the dictator and 27 per cent state they respect him. Positive feelings are generally greater among the over-35: 82 per cent in Armenian, 78 per cent in Russian and 75 per cent in Moldova.

In Georgia and Armenia only 24 per cent and 18 per cent respectively did not see in Stalin “a cruel tyrant, responsible for the deaths of millions”. In Russia, only three per cent of those interviewed associate the USSR with human rights violations, repressions, and totalitarianism.

The percentage of the “indifferent”, a social group seen as potentially most susceptible to propaganda, is high; in Armenia it constitutes 25 per cent, while in Russia it is 33 per cent.

One of the strategies the Russian government uses to erasethe traumatic Soviet past from collective memory is the censorship and pressure on critical voices.

In 2021, the human rights NGO Memorial, set up to examine crimes committed under Stalin, was banned by the Supreme Court. Declared “a foreign agent” the group, which was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2022, cannot operate in Russia.

Meanwhile Russian-language internet, and in particular social networks, teems with groups whose aim is celebrating the Soviet Union’s grandeur and nurturing nostalgia of the “good days” in the USSR.

One of the most popular Instagram communities, CCCP Nostalgia, has 266,000 followers; Memorial just over 16,400.

This article was published by IWPR and prepared under the “Amplify, Verify, Engage (AVE) Project” implemented with the financial support of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Norway.