Afghanistan Covid-19 Poverty Monitor – Analysis

By AREU

Areas Of Concern

Economic

The poverty rate rose from 43.7% in Autumn 2019 to 51% in Spring 2020.3 The poverty rate was expected to increase further during 2020, and the latest estimates from UNDP moreover suggest that as much as 97% of the population could be living in poverty by the middle of 2022.

The increase in poverty also is mirrored by large self-reported income losses by the Afghan population. For example, before the pandemic between October 2019 to March 2020, quantitative analysis of survey data indicates that 61-62% of the population recorded their economic situation as being worse off compared to a year before the survey. However, from April to June 2020, 76% of the population recorded their economic situation being worse off, increasing to 81% of the population from July to September 2020.4

Market closures and disruptions to transportation due to Covid-19 have resulted in a loss of income for farmers, small businesses, salaried workers and casual day labourers. Respondents attributed these income losses to disruptions earlier in the pandemic caused by lockdowns and since then a reduction in demand for goods and services due to widespread economic downturn.

Respondents noted a lack of demand for goods due to disrupted export markets, higher costs of doing business such as the cost of building materials, and reduced demand for day labour. Salaried workers in education and manufacturing also reported losing their jobs during past lockdowns.

“There is no demand for grapes in the market. Traders cannot export grapes to India and Pakistan. When the market was good, one Mun (equal to 4kg in Herat province) of raisins was more than 500 Afghan afghani (AFN) ($5.44).5 That made a decent amount of money for us. But we did not make it now – the price has decreased to 250 AFN ($2.72).” Male respondent, 30, Rural Pashtun Zarghun, Herat

“I lost my job and salary. I was contracted to be a schoolteacher. I don’t get a salary anymore since schools are off due to Corona.” Female respondent, 28, Pashtun Zarghun

“My [son] is busy with construction works [but] during [the] lockdown he was not able to work outside… He was not able to earn enough to send us… Most of the people are jobless, as there is no more construction work as before. If they go to the city, there is not enough work too, due to corona and insecurity. There are no more NGOs to bring projects to villages for people.” Female respondent, 46, Pashtun Zarghun

One respondent whose household was displaced to Kandahar City drew distinctions between the impact of Covid-19 in rural versus urban areas, particularly with regards to the impact of disease containment measures on the ability to earn an income in urban areas.

“When we were in our district, people did not consider Covid-19 an obstacle for [their] family, livelihood, and daily wage labour. We did not have a quarantine in our community, and our district’s fatality rate was also meagre. On the other hand, people in Kandahar City lost their relatives. They faced quarantine and were not able to work during the day.” Male respondent, 26, Kandahar City

The heightened price of staple goods, particularly food, agricultural inputs, and fuel, is high among people’s immediate concerns. Many respondents consider these price increases to have been initially driven by market closures and transportation disruptions due to Covid-19 earlier in the pandemic, but more recent conflict and instability (see below) has been attributed to the continued increase.

“The price of every food item has increased. Before Covid-19 I was able to buy 10 litres of cooking for 600-700 AFN ($6.53-$7.62). Now, the price of the same cooking oil is more than 1,100 AFN ($11.97). In addition to this, the price of one litre of petrol was 25-30 AFN ($0.27-$0.32). After the start of Covid-19, it has reached 57 AFN ($0.62). When we ask shopkeepers why the price is so high, they say border closures. There is no transportation between countries and that has an impact on imports and exports.” Male respondent, 53, Pashtun Zarghun

“A bag of black fertiliser, which was 2,100 AFN ($22.86), costs 4,000 AFN ($43.54) now. I bought white fertiliser two weeks ago for 1,120 AFN ($12.19), but now it has reached 1,710 AFN ($18.61).” Male respondent, 53, Injil

Health

As with economic conditions, there were mixed experiences in food security since A majority of respondents report being directly affected by Covid-19 infection, either being infected themselves or reporting infections among household members and other close relatives. The health effects of these infections range from mild symptoms that passed without treatment to fatality. Access to health facilities is widely reported, though treatment costs and transportation disruptions have had an impact on people seeking treatment.

Many respondents sought treatment, though most emphasised the effect of the costs of these treatments on their households’ economic security, as well as lost time in employment and day labour. One respondent reported avoiding treatment due to misinformation about the dangers of attending a health facility for Covid-19.

“We are living with the fear of Corona. My son became sick last year, but fortunately, he became better soon. I was affected by Corona too last year. Thank God, I was healed and became better. My second son became sick too, as he was deported from the Iran border. People said he had Corona too, but his health was worse than ours. My daughter-in-law got Corona last year and the doctor gave [her] some medicine and she became better.” Female respondent, 56, Pashtun Zarghun

“Our financial situation has been getting worse since the start of Covid-19. My mother, my wife and I got sick., I did not have money to take them to a doctor… The other reason for not taking my mother to a doctor was that I heard many rumours that if a person is Covid-19 positive and you take him to a doctor, they will inject an IV to kill them and increase the number of dead people from Covid-19. Therefore, I did not dare to take my mother to a doctor. I was also sick for 15 days. Because I did not have money, I did not visit a doctor.” Male respondent, 25, Injil

Some respondents expressed a lack of concern or disbelief of the existence of Covid-19 in their communities despite signs that the disease is present.

“People in our village do not consider Covid-19 a severe issue. Even though most of the people in our village were sick, they thought they had flu or fever. We also lost a few people in our village during Covid-19. It was not confirmed that they were Covid-19 positive.” Male respondent, 65, Injil

“In our village, we had people clearly saying that Covid-19 cannot transmit to us. They did not take care of social distance, washing hands, etc. Therefore, after a couple of weeks, everyone in our village was affected with Covid-19, including my family. Fortunately, they got cured and did not go to a doctor. We did not test for Covid-19, but the fever and pain that we had in our body, was not the pain for flu. We were sure that we were Covid-19 positive.” Male respondent, 53, Pashtun Zarghun

Food Security

Afghanistan was not food secure before Covid-19 due to protracted years of conflict and severe droughts. The impacts of Covid-19 have worsened the situation for many rural and urban poor households. Across the country, quantitative analysis of survey data indicates that 69% of households before Covid-19 (October 2019– March 2020) had worried about not having enough food to eat, a figure which rose to 76% during the initial months of the pandemic (April–September 2020). More households during this same pandemic period compared to the preceding months also reported eating less, skipping meals, eating fewer kinds of food, and various other factors reflecting their heightened food insecurity.6

The majority of respondents reported few changes to their household’s food security, however, a smaller number reported becoming more food insecure as a result of Covid-19. Those households reporting little to no change may have therefore normalised their food insecurity.

“Before Covid-19 we consumed meat two or three times a week. We consume once every two weeks or once a week now.” Male respondent, 65, Injil

Social Cohesion

Multiple respondents raised concerns about the indirect effects of the Covid-19 crisis on household dynamics, social relationships, and wider social cohesion. The pressures of movement restrictions and lack of livelihood opportunities that have left many at home struggling to earn a living have placed a strain on relationships and led to interpersonal conflicts. Those who have been displaced due to instability, conflict and climate disasters also reported losing their social support networks and having added strains on their relationships due to the pressures of daily subsistence. Indeed, across the country, quantitative analysis of survey data indicates that in response to negative shocks, fewer households were able to rely on help from others during the pandemic months between April to September 2020, compared to the half-year before the pandemic.7

“[Covid-19] has collapsed our lives. It ruined the whole life we had. Do not leave your house. Do not go for work or other life matters; do not go to gatherings and parties. It has totally collapsed and paralysed [our lives].” Male respondent, 53, Injil

“When men are at home unemployed it is difficult for them to bear everything such as the noises of children etc. So, this has created lots of family conflicts, and family violence has increased.” Female respondent, 28, Pashtun Zarghun

Other Concerns Overlapping With Covid-19

Climate change: Afghanistan is one of the most vulnerable countries to climate change due to “the high dependence of its population on agricultural livelihoods, fragile environment, poor socio-economic development, high frequency of natural hazards and over four decades of conflict,” according to UNEP’s Afghanistan Vulnerability and Adaptation Technical Assessment Report. Just before the pandemic, recent drought in 2018 and 2019 displaced over 400,000 people in the country, alongside flash floods in 2019 which displaced another 42,000 people. Respondents, namely those in rural areas dependent on agriculture, considered recent floods and droughts to be a leading threat to their household’s wellbeing. Multiple respondents noted that the impacts of floods had worsened in the last two years.

“The flood destroyed our farms last year badly. This year floods also came and destroyed some parts of our farms. It had a huge impact on our harvest.” Male respondent, 42, Pashtun Zarghun

In the quantitative analysis of survey data from 2019/20 moreover, shocks related to disasters (e.g., drought, floods), agriculture, or food/farm prices was associated with a higher probability of poverty and welfare loss, particularly during the summer of 2020.8

Political instability and insecurity: Longstanding insecurity and conflict in the sampled areas were at the forefront of most households’ concerns. Many respondents have been personally affected through the loss of one or more family members, disrupted livelihoods or displacement. Nearly all reported indirect effects with regards to community relationships, access to services and support and reduced coping strategies.

It should be noted that interviews took place immediately before the recent Taliban takeover and withdrawal of international actors and the findings, therefore, do not reflect changes since these major events. Data collection in Kandahar was carried out in June and Herat in July 2021. The team were in Herat province when the Taliban took control of Islam Qala and Toorghondi borders and Pashtoon Zarghoon in Herat.

“There are thieves who stop people and take their mobile phones which may cost 6,000 AFN ($65.32) or even take motorbikes from people. Such incidents happen a lot. The security situation has a lot of impact on farmers and everyone. As a result, it has affected our income and livelihood.” Male respondent, 65, Injil

In the quantitative analysis of survey data from 2019/20, insecurity and displacement were associated with a higher probability of poverty and welfare loss. This probability was particularly high during the summer (July–September) of 2020.9

Coping Strategies

The quantitative analysis of survey data in 2019/20 points to a range of coping strategies in response to negative shocks experienced by households. Out of the active coping strategies recorded, over half of households experiencing shocks reduced expenditures as their main strategy, and also relied on less amount or quality of food. During the survey months overlapping with Covid-19 (April– September 2020), moreover, these strategies were more common compared to the months before the pandemic. Other coping strategies emerging from the qualitative data are highlighted below.10

Loans and long-term debt: Many respondents report coping with lost income, increased costs of staple goods, health costs and other major expenses – such as dowry and wedding costs – by taking out loans. In the quantitative analysis of survey data, reliance on credit or loans was relatively consistent before and during the pandemic. In the qualitative data, among those who have taken loans, most expressed challenges in paying these back and are at risk of long-term indebtedness.

“I get loans from relatives and neighbours to provide daily expenses such as food or other necessary needs. I get a loan to buy groceries when I need to. I get a loan whenever my family members become sick and have to see a doctor.” Female respondent, 46, Pashtun Zarghun

“There is no one in this village who has not become indebted under these circumstances. Either he did not have the money for medicine or was short of money for his daily needs. They borrowed from their neighbour to repay later. If this drought and Corona continue, we would have no other option but to spend our whole lives in debt.” Male respondent, 53, Injil

Displacement, migration and remittances: The Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre says: “Afghanistan faces one of the world’s most acute internal displacement crises as it suffers protracted conflict and insecurity as well as recurring disasters, including droughts, floods, storms and earthquakes. Displacement has become a common coping strategy for many Afghans and, in some cases, an inevitable feature of life for multiple generations. Over 404,000 new displacements associated with conflict and violence were recorded in 2020, and there were 3.5 million people internally displaced as a result at the end of the year. This latter figure is an 18% increase compared with 2019 and the highest figure in more than a decade.”

“When the fighting started between the government and the Taliban, they started shelling each other. Because of the shooting in our village, 11 people have died. Among them, three kids were also injured. After this incident, I have decided to go to Kandahar city. When I was displaced from Kandahar, we did not have a house to live in. Then one of the relatives found a place for us, and for the last three months, we have been living here.” Male respondent, 25, Kandahar City

“As soon as the wars started, people started leaving their home and village. Eighty percent of people have been displaced to other provinces and districts. Only 20% of people remained. Those who are not able to go somewhere, and do not have means and resources of movement, stay there.” Male respondent, 27, Injil

Migration to Iran to earn income was also reported by many households as a common coping strategy, though it was noted that this has become more difficult due to Covid-19 border closures.

“Apart from agriculture, there is no other work for us. Our village is a tiny village – 60 to 70 people have migrated to Iran from our village. They went there for work. Most of them are those people who are the head of a family, or they have to pay their bride price.” Male respondent, 65, Injil

“One of my sons is in Iran, it is about one year. He went legally with a passport, as the border was closed, so he had to stay there. He is living there illegally as his passport is invalid now.” Female respondent, 40, Pashtun Zarghun

More generally reflecting this decline in migration, remittances also fell during the pandemic. While inflows totalled $828.6 million in 2019, they fell to $788.9 million by 2020.

Support from government, NGOs and Taliban: To overcome and reduce the economic hardship of Covid-19, the government of Afghanistan implemented a range of aid programmes in which they identified the vulnerable people to whom they distributed cash. With the support of other international partners like WFP, food aid like flour, bread, wheat and lentils were distributed to people at risk of economic hardship. Social networks, local traders, people in business, and other wealthy people also supported those who lost their jobs or income sources.

Despite the reported prevalence of these programmes, few respondents indicated that they had received any formal support through the Covid-19 crisis other than a small number of food rations and small one-off cash transfers. Most reported that the distribution of support to households in need was very opaque and largely depended on relationships with local leaders.

“No, we did not receive any aid. Only one time they sent us a carton of soup to distribute to the household.” Male respondent, 65, Injil

“Our Imam of the Masjid wrote our name. After some time, they called our Imam and went and took the aid package. First, I received food items (a sack of flour oil and other food items), and the second time, I received 3,000 AFN ($32.66). I also received three pieces of bread per day for a week.” Male respondent, 42, Dand

“Our Malik (head of village) got killed and the new Malik is not very active. Maliks have a vital role in these aid packages. If we have an active Malik, he finds support or aid for his villagers. The reason is, he should visit the district office every day or twice a week and find information about aid and other support. Our ex-Malik was very active in it. When he passed away, we did not receive any aid.” Male respondent, 53, Dand

Source: This article was published by Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit (AREU)

End notes

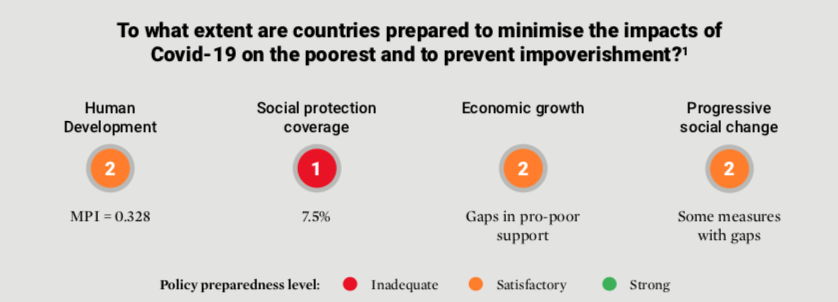

- Read more on CPAN’s Poverty Eradication Policy Preparedness Index adapted for Covid-19.

- Johns Hopkins Covid-19 Dashboard as of 29 November 2021.

- NSIA, (2021) Income, Expenditure, and Labour Force Survey (IE&LFS) 2019/20.

- Diwakar, 2022, forthcoming, based on analysis of IE&LFS data.

- All currency converted into USD$ with www.xe.com on 18 February 2022.

- Diwakar, 2022, forthcoming, based on analysis of IE&LFS data.

- Diwakar, 2022, forthcoming, based on analysis of IE&LFS data.

- Diwakar, 2022, forthcoming.

- Diwakar, 2022, forthcoming.

- Diwakar, 2022, forthcoming, based on analysis of IE&LFS data.