Could Canadian Crude Improve European Energy Security? – Analysis

By Larry Hughes

Introduction

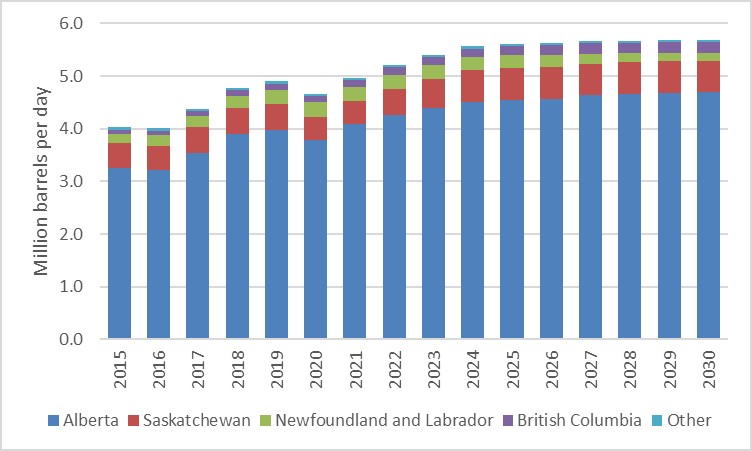

In 2021, Canada produced 4.74 million barrels of crude oil a day (mmbbl/d), making it the world’s fourth largest producer of crude oil. Projections suggest that by 2030, Canada will have increased its production to between 5.79 and 6.18 mmbbl/d.

Canada’s expected rise in production would appear to have come at a fortuitous moment, as the sanctions placed on Russian crude oil in response to its invasion of Ukraine are impacting energy security around the world. However, both the availability and affordability of crude oil and refined petroleum products has become an issue in many countries.

The European Union responded to the Russian invasion with a series of sanctions packages targeting Russian industry, oligarchs, and high-level officials.

In early June, the EU announced its sixth package of sanctions. This includes measures to immediately ban the import of two-thirds of Russian crude oil supplied to the EU by tanker. The ban is to increase to 90% by the December 2022, with indefinite exemptions for Hungary, Slovakia, and the Czech Republic, and time-limited exemptions for Croatia and Bulgaria.

Additional energy-related measures in the package include a complete phaseout of Russian refined oil products(such as gasoline, diesel, jet fuel, and heating oil) by February 2023 and a ban on EU insurers and reinsurers of the transportation of Russia crude oil by sea.

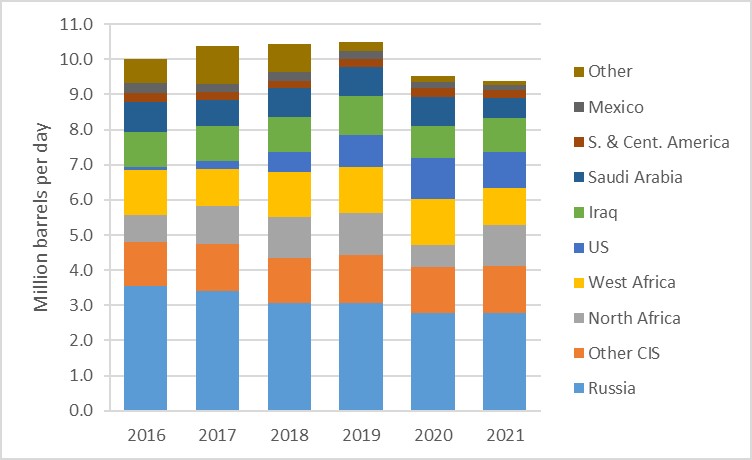

In 2021, Europe (consisting of the EU, and other countries such as Iceland, Switzerland, Turkey, Ukraine, and the United Kingdom) imported about 9.39 mmbbl/d (excluding European production from the North Sea). Of this, 2.78 mmbbl/d were imported from Russia both by ship and pipeline (see Figure 1).

In 2021, Russian crude oil exports to Europe amounted to about 60% of Canada’s total production. While Canada will not be able to replace all of Russia’s exports, it has offered to help Europe meet some of its crude oil needs.

To do so, Canada must:

- Find new sources of crude oil for export. These must exceed any supplies already sent to Europe from Canada.

- Have sufficient infrastructure in place to move the crude oil to tidewater and onto vessels bound for Europe.

In this analysis, we examine where crude oil is being produced in Canada, projected future volumes, and possible routes to Europe.

Producers

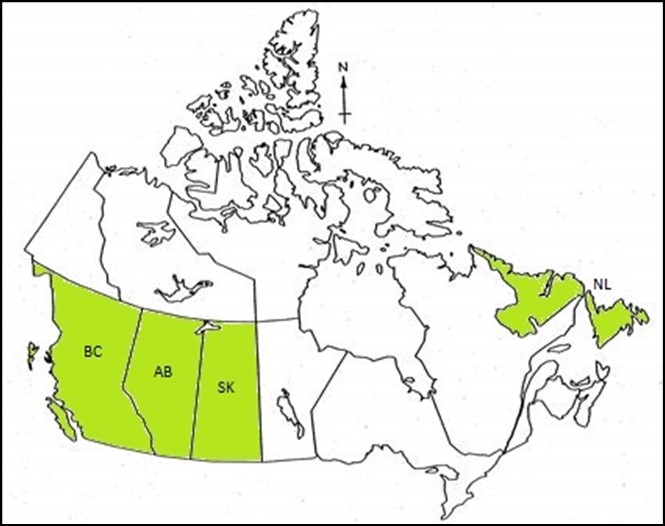

Crude oil and natural gas liquids (NGLs) are produced in seven Canadian provinces and one territory. Only the provinces producing more than one percent of Canada’s total are considered.

The Canada Energy Regulator (CER) projects Canada’s production of crude oil and NGLs to increase this decade, the volume depending on the policy scenario.

In CER’s Current Policies scenario, actions on greenhouse emissions are assumed to be those in place today. The production of crude oil and NGLs increases from 2021 to 2030 by 22% (see Figure 2).

CER’s Evolving Policies scenario assumes that Canada’s greenhouse gas reduction targets are met, limiting the production of crude oil and NGLs. Between 2021 and 2030, production increases by about 14.5% (see Figure 3).

We now consider the four major oil producing provinces, production, and projections for 2030 (see Figure 4).

Alberta

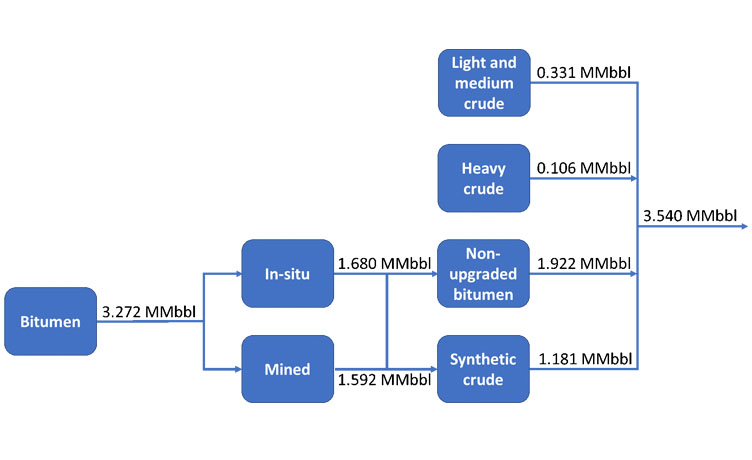

In 2021, Alberta, which lies atop the Western Canadian Sedimentary Basin (WCSB), produced almost 83 percent of Canada’s crude oil (about 3.54 mmbbl/d) and 76 percent of the NGLs (about 0.343 mmbbl/d).

The largest source of hydrocarbons in Alberta is bitumen. It is extracted by open-pit mining or in situ using steam, depending on the depth of the bitumen. In-situ extraction has a smaller footprint, uses less water, and is less expensive than mining, but steam production makes it more carbon intensive than mining. Concerns over carbon emissions have prompted companies and the Alberta government to develop various forms of carbon capture and storage.

Alberta’s bitumen has an API of between 8° and 14°, which is too dense for pipeline transportation and most refineries. To reduce its viscosity, the extracted bitumen is diluted to “dilbit” or diluted bitumen, which is equivalent to a heavy crude with an of API 20° to 22°. The diluted bitumen can be sent to either an upgrader to create a synthetic crude with an API of 30° to 35° for low-complexity refineries or directly to a high-conversion refinery as non-upgraded bitumen.

The two most notable benchmarks for products derived from Canadian bitumen are:

- Western Canadian Select (WCS) is a blend of heavy crude, bitumen, and synthetic crude oil with an API of about 21° and a high sulphur content (3.0 to 3.5 percent). It is a dilbit. Unlike unblended bitumen, WCS can be moved by pipeline. WCS is usually sold at a significant discount to lighter crudes due to high supply and low demand.

- Synthetic Crude Oil (SCO) is the product of upgrading bitumen into a light sweet crude (i.e., a very low-sulphur crude with an API of 31° to 38°), meaning it can be refined in a low-complexity refinery.

In addition to bitumen, Alberta is the largest producer of conventional light and medium crude in Canada, accounting for about 41 percent of the total. It also supplies about a quarter of Canada’s heavy crude.

The sources of Alberta’s hydrocarbons produced in 2021 are shown in Figure 5.

Growth in Alberta’s oil production between 2021 and 2030 relies heavily on bitumen, synthetic crude, and light and medium crude in both the Current and Evolving Policies scenarios. Heavy oil production is expected to decline in both. In Current Policies, NGLs are expected to decline, while in Evolving Policies, it increases.

By 2030, overall output increases to 4.94 and 4.69 mmbbl/d for the Current and Evolving scenarios, respectively.

Saskatchewan

Saskatchewan is Canada’s second largest producer of crude oil which, like Alberta, overlies the WCSB. In 2021, it produced about 0.437 mmbbl/d of crude oil or 10 percent of Canada’s total. Saskatchewan produces negligible volumes of NGLs.

The Current Policies and Evolving Policies projections both expect Saskatchewan’s production increase between 2021 and 2024, and then plateau until 2030. The Current Policies plateau averages 0.685 mmbbl/d and the Evolving Policies, 0.605 mmbbl/d. The Evolving Policies scenario is in keeping with the Government of Saskatchewan’s production and emissions target for 2030.

Newfoundland and Labrador

The third largest oil producing region in Canada is offshore Newfoundland and Labrador in the Atlantic Ocean on the country’s east coast. In 2021, the province produced about 0.257 mmbbl/d of crude oil or six percent of Canada’s total. Any NGLs are included with the oil production and not counted separately.

The extracted crude oil is stored in shuttle tankers at the production platforms. When full, the tankers return to the island of Newfoundland and offload their crude into storage for transshipment to other jurisdictions.

Newfoundland and Labrador’s production of light and medium crude peaked in 2017. The decline has been offset with an increase in heavy crude production. However, production is projected to begin to decline in 2023 in both scenarios. The principal difference in the scenarios is that in the Current Policies scenario light crude declines more rapidly than in the Evolving Policies. By 2030, production is expected to fall to 0.21 and 0.15 mmbbl/d in the Current and Evolving Policies, respectively.

British Colombia

In 2021, British Columbia produced about 0.25 percent of Canada’s light and medium crude, but 22 percent of Canada’s NGLs. NGLs are found in tight gas deposits in the northeast of the province (part of the WCSB) and the province’s far north.

Crude oil production is projected to decline in both the Current Policies and Evolving Policies scenarios, while NGLs are expected to double this decade (from 0.1 to 0.2 mmbbl/d) between 2021 and 2030.

Routes

Canada is bounded by three coasts: to the west, the Pacific Ocean; the east, the Atlantic Ocean; and the north, the waters of the Arctic Archipelago; and to the south, a land border with the United States. These geographic factors have determined Canadian crude oil exports since the 1950s.

In 2021, Canada produced about 4.3 million barrels of crude oil and NGLs a day. Of this, 3.8 million barrels were exported. The effect of geography and economic expediency resulted in most of Canada’s production being shipped south to the United States (see Figure 6).

Most of western Canada’s crude oil is shipped by pipeline to refineries in the United States, as well as to central and eastern Canada. Smaller volumes are moved by ship and rail. For example, in 2020, an estimated 87.6 percent of Canadian crude oil was carried by pipeline, 7.8 percent by marine, and 4.6 percent by rail.

(The volume of crude carried by rail in Canada is dictated by the differential between Canadian and U.S. crude oil prices, the wider the differential, the more attractive rail becomes. Canada’s total rail loading capacity (i.e., the ability to load oil onto a train) is about 1.33 mmbbl/d, about 60 percent is in Alberta.)

We now consider Canada’s existing or potential routes for moving crude oil to Europe.

West

The TransMountain pipeline runs 1,150 kilometres from Edmonton, Alberta on the east of the Canadian Cordillera(including the Rocky and Coast Mountain ranges) to Burnaby, British Columbia on the Pacific coast (see Figure 7). The pipeline has a capacity of about 300,000 barrels per day and can transport heavy crude oil as well as refined product. Crude oil is shipped westward from fields in Alberta from the Edmonton terminal.

At the Sumas terminal in Abbotsford, British Columbia, crude oil either continues westward on the TransMountain pipeline to Burnaby or is shipped south to three refineries in Washington State connected to TransMountain Puget Sound Pipeline System.

The Burnaby terminal, in the Port of Vancouver, supplies crude oil to the Parkland Burnaby Refinery and the TransMountain Westridge Marine Terminal for export. The Westridge Marine Terminal is being expanded from its current capacity to handle five AFRAmax crude carriers a month to 34 (an AFRAmax tanker can carry about 600,000 bbl of crude oil).

At present, about half of the flow goes to the refineries in Washington State and the remainder is sent to Burnaby. It takes about six days for a barrel to reach Burnaby from Edmonton.

The TransMountain pipeline has been operating since 1953. In 2012, in response to the anticipated growth in oil sands production from northern Alberta and support from oil carriers, Kinder-Morgan (the owners of the pipeline at that time) announced their intention to increase the pipeline’s capacity threefold, from 300,000 barrels/day to 890,000 barrels/day. In 2013, Kinder Morgan submitted their proposal to Canada’s National Energy Board.

Construction of the proposed TransMountain Expansion project (or simply TMX) was to have started in 2017 and been completed by 2019. However, it was delayed because of protests, court challenges, and Canadian government indecision. In 2019, Kinder-Morgan gave up on the project and sold it to the Canadian government for C$4.5 billion. The government has continued the project, which is expected to be completed in the third quarter of 2023, at an estimated cost of C$21.4 billion to the Canadian taxpayer.

Depending on the available capacity of the new pipeline, Canadian crude producers are expecting to increase their output by 400,000 to 500,000 bbl/day for export to the Asia-Pacific market.

A number of restrictions are placed on tankers using the Port of Vancouver, notably the maximum tanker capacity is 120,000 tonnes (the maximum AFRAmax tanker size) and vessels of this size can only be loaded to 80% capacity. With the completion of TMX, the number of tankers visiting the Port of Vancouver is expected to increase tenfold, from between 30 to 50 a year to about 400.

Routes to Europe

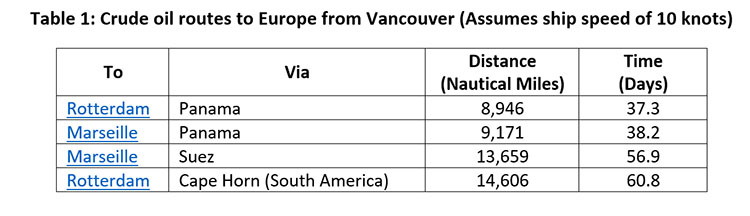

Although most crude shipments are expected to be sent to the Asia-Pacific, crude oil and its products can be sent to Europe from Vancouver by several routes, including the Panama Canal, the Suez Canal, and around Cape Horn (see Table 1).

Shipping oil from Vancouver to Shanghai takes an estimated 21.2 days. It is a more attractive destination than ports in Europe because the time required to operate the vessel is less.

South US Gulf Coast

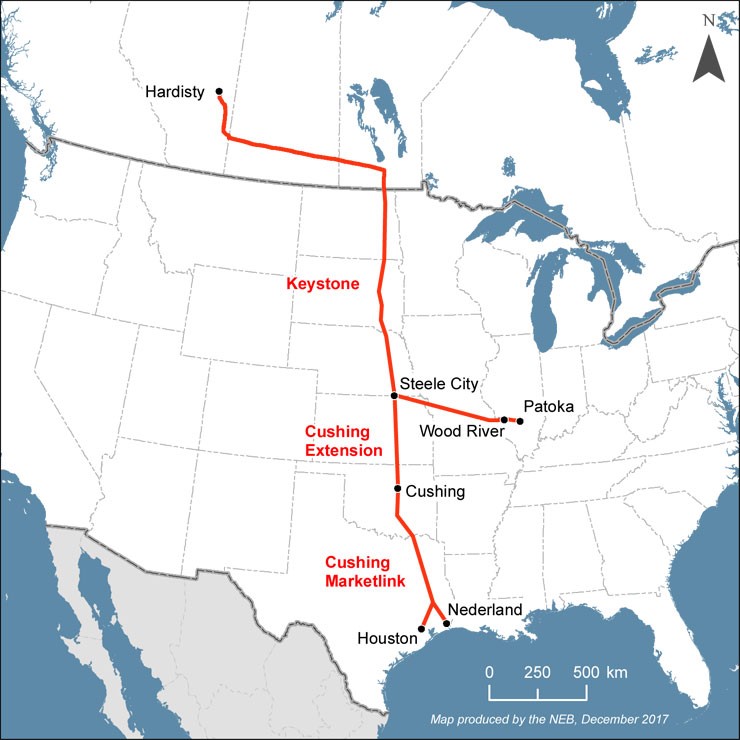

Most of Canada’s CER-regulated oil pipelines from Western Canada enter the U.S. destined for markets in either the U.S. or eastern Canada. The Keystone oil pipeline has a direct route south to Cushing, Oklahoma, and through a series of extensions, the U.S. Gulf Coast (see Figure 8). This may be a route for moving Canadian crude to Europe; however, European refiners’ preference for lighter crudes, pipeline transit fees (about $10/bbl), and President Biden’s decision to open the Strategic Petroleum Reserve, are hampering Canadian exports to Europe.

Canadian crude oil reaching the Gulf Coast is being used in refineries as a replacement for heavy crude previously imported from Venezuela and being exported to India, China, and South Korea.

If pipeline or rail capacity is available, Canadian crude oil could be shipped to Europe from the Gulf Coast. However, U.S. producers are already exporting near-record volumes of crude oil to Europe to replace Russian crude oil. Export facilities on the Gulf Coast are also operating at near full capacity, in part because of congestion on the shipping canals.

An alternative is to use Canadian crude oil to replace crude oil refined in the U.S., allowing the U.S. crude oil to be shipped to Europe.

A tanker traveling at 10 knots from Houston, Texas to Rotterdam takes about 21 days.

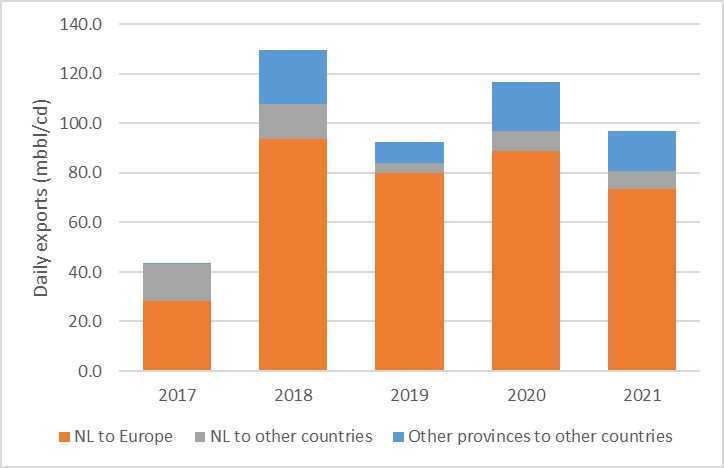

East: Newfoundland and Labrador to Europe

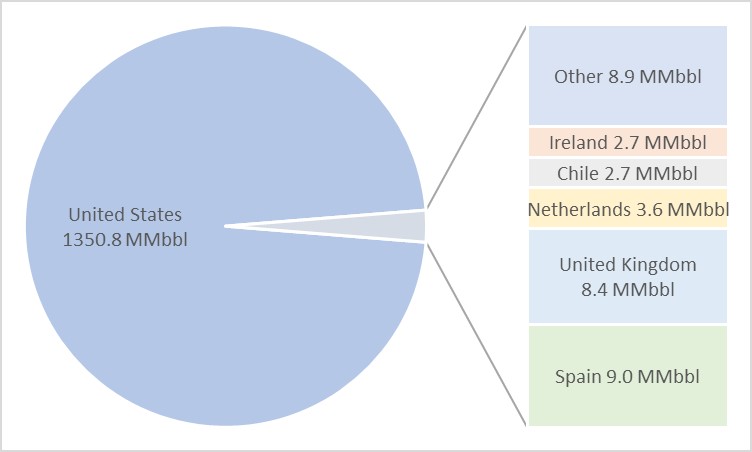

Most of Newfoundland and Labrador’s production is shipped to the United States, although a sizeable volume is exported to Europe (see Figure 9). Newfoundland and Labrador is the major supplier of Canadian crude oil to non-U.S. destinations.

In 2021, Newfoundland and Labrador exported about 246 thousand barrels a day (mbbl/d) of crude oil. Of this, 73.3 mbbl/d were shipped to Europe (96 percent of Canada’s total shipments to Europe). The remainder was destined for Chile (7.3 mbbl/d) and the United States (165.2 mbbl/d). Assuming that the entire volume of Newfoundland and Labrador’s production could be directed to Europe rather than to existing recipients, an additional 172.5 mbbl/d would be available for European use.

If existing non-European exports cannot be redirected, the volume available for Europe would be minimal because production gains are projected to be offset by production declines by the mid-2020s in both the Current and Evolving Policy scenarios.

A tanker from St. John’s to Rotterdam travelling at 10 knots can make the voyage in 9.4 days.

Potential Routes

The potential of routes from three ports, Montreal, Saint John, and Churchill, are considered (see Figure 10).

East: Montreal

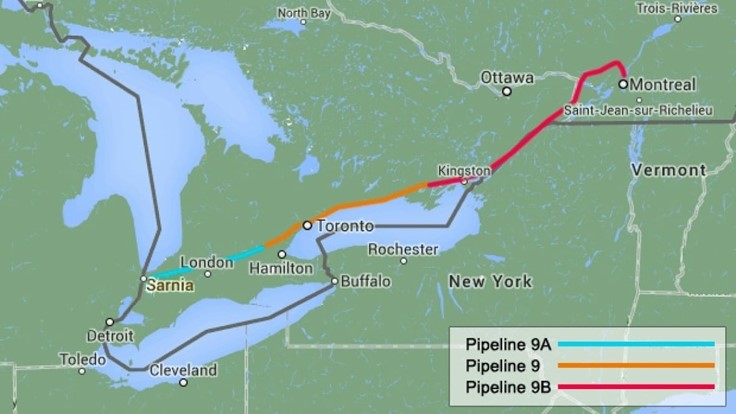

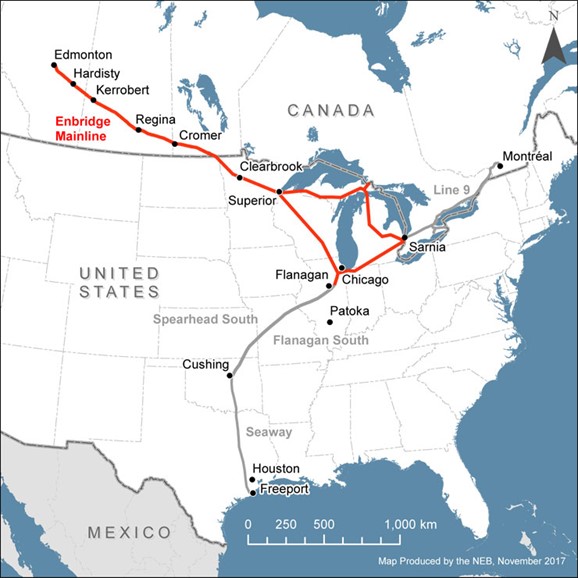

The Port of Montreal has facilities to load marine tankers with crude oil for shipping to the Valero refinery in Lévis. The Port is connected to Sarnia by Line 9 (see Figure 11) and from Sarnia to terminals in Western Canada by the Canadian Mainline (see Figure 12). If spare capacity exists in the Port of Montreal’s crude oil loading infrastructure, the port could be used to export Western Canadian crude oil to Europe.

That said, the volume of crude oil available for shipping depends on the available pipeline capacity in Line 9 and the Canadian Mainline. At the time of writing (August 2022), Line 9 has spare capacity of about 100 Mbbl/d into Montreal but the Canadian Mainline entering the U.S. has little or no spare capacity.

There is a small 40 Mbbl/d pipeline running from Montreal to Portland, Maine.

If crude oil was available, it could be shipped from Montreal to Rotterdam in 13.2 days at 10 knots.

East: Saint John

Canada’s largest refinery is in Saint John, New Brunswick. It supplies refined products to the Northeastern United States and eastern Canada. Most of the crude oil it uses is imported. In 2013, TransCanada Pipelines proposed Energy East, an extension of its existing pipeline network to Saint John to give western Canadian crude oil producers access to the refinery and the Atlantic Basin. The owners of the refinery had committed to spending $300 million for building infrastructure to export crude oil.

Energy East was abandoned in 2017.

The refinery has a purpose-built railyard for handling crude-by-rail shipments. If large volumes of Western Canadian crude oil were shipped to Saint John, it could be used by the Saint John refinery rather than shipping it overseas. This could be an attractive option for the refinery depending on the price differential of the imported crude with that from Western Canada. Moreover, it would make the imported crude oil currently used by the refinery available to European refineries.

If crude oil could be shipped from Saint John, it would take an estimated 12.7 days to reach Rotterdam at 10 knots.

North: Churchill, Manitoba by Rail or Pipeline

In addition to the routes described above, the town of Churchill in northern Manitoba on Hudson Bay offers a fourth possibility.

A tanker sailing from Churchill to Rotterdam would take about 13.7 days at 10 knots. If oil transit time within Canada is considered, Churchill offers the fastest route for western Canadian crude oil to reach Europe.

However, there are several logistical issues that need to be addressed before a northern route can be considered a viable alternative.

Presently, the only way of shipping crude to Churchill is by rail from Le Pas, Manitoba, a journey of about 1,000 kilometres. The line was originally built in the 1920s as an alternate route for shipping western Canadian grain to overseas markets. It fell into disrepair over the past decade and its owner sold the line to a group of local communities and Indigenous groups. Remediation work started on the line in late 2021 and is expected to be completed within the next two years.

If the upgraded track is designed to handle crude oil unit-trains, crude oil could be shipped from the Hardisty terminal in Alberta to Churchill.

At present, there are no pipelines to Churchill. To move crude by pipeline to Churchill will require the construction of a pipeline from one of a number of oil storage terminals in Alberta or Saskatchewan. Alternatively, a spur from the Canadian Mainline could be built to follow the railway’s right-of-way to Churchill.

The rail line traverses areas of permafrost which have experienced melting over the past decade.

The effect of climate change on the permafrost is changing the landscape and making shipping by rail potentially dangerous with threat of derailments. Construction of a pipeline over melting permafrost causing frost heaves and slope instability could also lead to spills. The threat of permafrost melt under the rail line has resulted in the Canadian federal government spending $4.4 million to research the problem.

Crude oil export infrastructure will need to be built in Churchill.

Finally, ships sailing to and from Churchill must pass through the Labrador Sea, Hudson Strait, and Hudson Bay. Although there is a limited ice-free season, shipping through the Hudson Strait does occur throughout the year.

Only ice-class oil tankers could sail this route when the sea lanes are icebound. They would probably need ice-breaker escort to ensure safe passage through ice exceeding the tanker’s ice-thickness limit. Oil spills in the Arcticcould be catastrophic.

Summary

Canada is the world’s fourth largest producer of crude oil. Unlike most other exporters, Canada effectively has a single export market, the United States. In doing so, most of its export infrastructure (both pipeline and rail) is geared to move crude oil to the U.S.

This will change in 2023, with the completion of the TMX pipeline from Alberta to Burnaby, British Columbia. However, the TMX pipeline is intended to make Canadian crude oil available to Asian, not European, markets. Shipping from Burnaby to Europe is possible via the Panama Canal, but the sailing time would increase the cost of the crude oil.

Newfoundland and Labrador already exports crude oil to Europe. To make an impact on the European market requires an increase in the volume produced. This would appear unlikely as the province’s production is expected to decline this decade.

Shipping crude oil and NGLs from Canada to Europe via the U.S. Gulf Coast is hampered by transportation constraints and costs. If Canadian crude oil replaced U.S. crude oil, the U.S. crude oil could be shipped to Europe.

Exports from Montreal are another possible route. However, the volume of crude that can be shipped is limited by pipeline capacity from western Canada to Montreal.

Potential routes exist, notably from Churchill, Manitoba or Saint John, New Brunswick, but the crude would need to be shipped by rail to the ports and the ports are presently not equipped to export crude oil.

Although Canada is expected to increase its production of crude oil, the lack of infrastructure and the cost of shipping by pipeline or rail to tidewater are impediments for Canadian crude oil reaching Europe.

Despite its crude oil resources, its focus on exports to the United States means Canadian crude oil (like its natural gas) is unable to help maintain or improve European energy security.

This article was published by Geopolitical Monitor.com