How Switzerland Is Preparing For Nuclear Escalation

By SwissInfo

As the war in Ukraine escalates, Russian President Vladimir Putin has threatened to use his nuclear arsenal, fuelling fears across Europe. For its part, Switzerland is well prepared, but not even Swiss bunkers will be enough in the event of a large-scale nuclear war.

By Sara Ibrahim and Sibilla Bondolfi

The war in Ukraine continues unabated, with no end in sight. The Kremlin has responded harshly to the advance of Ukrainian troops into Russian-occupied territories, bombing cities and strategic infrastructure. Putin has repeatedly threatened the use of nuclear weapons to “defend the territorial integrity of our homeland”, including Ukrainian territories he illegally annexed.

Most analysts agree that the risk of a Russian nuclear attack in Ukraine remains low. Besides not guaranteeing the achievement of the Kremlin’s military objectives, the use of nuclear weapons could trigger a NATO response and would isolate Russia internationally. However, Moscow might decide to use such weapons – most likely smaller “tactical nuclear weapons” with low destructive power – as a last resort to stop the Ukrainian counteroffensive.

The danger of nuclear weapon use is therefore constantly increasing, says Stephen Herzog, a nuclear weapons expert at the Centre for Security Studies (CSS) at the federal technology institute ETH Zurich. “The effects of a nuclear war would be devastating for Ukraine, Europe and beyond. It is necessary to plan for the scenarios and be ready,” he says.

How prepared is Switzerland?

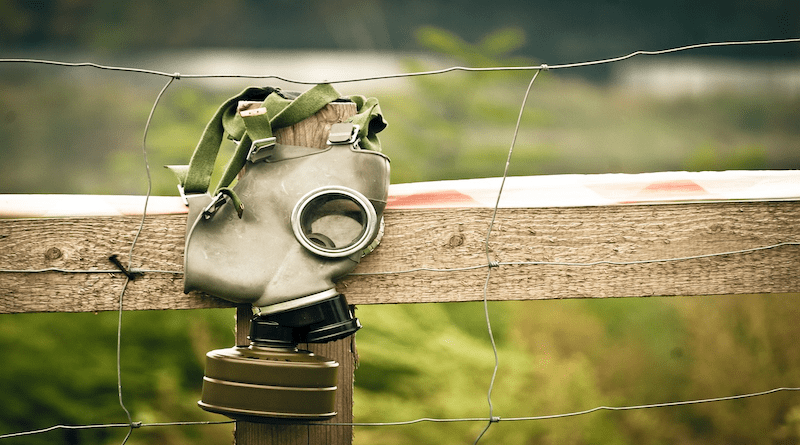

Switzerland appears to be relatively well prepared for the consequences of a nuclear event in Ukraine. The government has improved its protection against nuclear, biological and chemical (NBC) threats and hazards since the 2011 accident at the Fukushima nuclear power plant in Japan.

“Over the past ten years Switzerland has reinforced its level of nuclear and radiological protection, which was already high, and is in a good position,” says Anne Eckhardt, a biophysicist and chair of the NBC Commission of the Federal Office for Civil Protection (FOCP). Eckhardt also claims that Switzerland would have the capacity to provide medical assistance to people from areas affected by radiological accidents.

In a 2019 report, the NBC Commission listed quality infrastructure as a particular Swiss strength. This includes the Spiez Laboratory, a national centre for the analysis of NBC threats.

But an international comparison shows that the network of bomb shelters scattered throughout the country, capable of accommodating the entire population in case of need, is Switzerland’s real asset. The country has more than 360,000 of them, a unique case in Europe and the world.

“Although many European countries are developing or have civil or military nuclear response plans, they simply do not have Switzerland’s shelter infrastructure,” Herzog says. In countries like Romania and Slovakia that are closer to Ukraine and thus more exposed to the consequences of a nuclear war in the region, statistics on bomb shelters often include basements and garages. But these would be insufficient to protect the population in the event of a major nuclear accident, he explains. Sweden and Finland, on the other hand, could compete with Switzerland in terms of the number of shelters, but the coverage is significantly lower than in Switzerland.

Swiss model is not perfect

However, Switzerland could also do more. Not all cantons comply with the federal obligation to have a shelter within a 30-minute walk for every inhabitant: the worst-off are Geneva, Basel City and Neuchâtel. A recent FOCP report also pointed out the poor state of maintenance of the civil defence bunkers, noting 230 deficiencies in Swiss NBC protection.

The most serious deficiencies are related to both the inadequate division of tasks between the cantons and the federal government in the event of an emergency, and this division within the federal administration itself. The report also pointed out a lack of protective equipment.

All this is aggravated by a shortage of NBC specialists who can promptly assess the situation and advise on the most appropriate measures to be taken. According to Eckhardt, with the abandonment of nuclear power generation, important skills are also being lost: many people with nuclear experience are retiring and it is difficult to replace them.

These shortages highlight another complication: very fast technological and scientific progress poses new challenges and threats that are more complex to predict and deal with than decades ago. Russia, for instance, has modernised its nuclear arsenal, which now includes a wide range of tactical weapons (around 2,000), from nuclear artillery shells to half-tonne warheads.

“We have to take into account that ultimately no one is perfectly prepared, not even in Switzerland,” says Eckhardt.

What would the consequences be?

So-called “tactical” nuclear weapons range in power from less than one kilotonne to 50 kilotonnes (the bomb dropped on Hiroshima in the Second World War had a power of 15 kilotonnes). If Russia were to use them, the consequences could vary greatly.

According to Andreas Bucher of the FOCP’s communication office, the use of tactical nuclear weapons in Ukraine would not endanger the health of the Swiss population. Eckhardt agrees.

The radiation released by these weapons would probably be lower than what was produced by the Hiroshima bomb or the Chernobyl explosion. Specialist Walter Rüegg explained in an interview with the Neue Zürcher Zeitung newspaper that this is because tactical nuclear weapons contain little fissile material.

The FOCP therefore does not expect that it will be necessary to use the shelters if a nuclear weapon were to be used by Russia. At most, Bucher’s office says, there could be bans on hunting, grazing and the consumption of certain foods. The government does not even envisage distributing iodine tablets, as they do not protect against all radioactive elements, but are mainly used when a serious accident occurs at a nuclear plant. (All Swiss residents living within 50 kilometres of a nuclear power plant receive iodine tablets from the government in case of an accident).

The explosion of a nuclear power plant in Ukraine worries the FOCP the most, as it would have far more critical radiation consequences for Switzerland than the use of a nuclear bomb.

Prevention is better than cure

But if a bomb were to be used, there are many variables that would determine the degree of fallout from the event. These include weather conditions, the explosive yield of the weapons and the altitude of the detonations.

Some scenarios indicate that the distance to the war zone and the network of shelters would protect Switzerland from radioactivity. “But in other scenarios, the Swiss population and agriculture could be affected,” Herzog says.

Moreover, if NATO member states bordering Switzerland (Germany, France, Italy) were to be directly affected by a bombing, the risks for the Swiss population would increase dramatically. Although this hypothesis remains highly unlikely, according to Herzog, the authorities must increase emergency preparedness at the national level.

Switzerland is already doing this. At the end of September, the government set up a federal strategic management staff to ensure a rapid response in case of a nuclear event.

Measures like this are important but they are not enough, believes Wilfred Wan, an expert on weapons of mass destruction at the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI).

“Even if some countries like Switzerland have bomb shelters or national emergency procedures, any state would be overwhelmed by the devastating consequences of nuclear weapons,” says Wan. That is why it is important to talk about prevention rather than reaction, he says.

A United Nations study indicated that neither individual states nor the international humanitarian system would be able to react promptly and rapidly to the wide range of possible effects related to the use of nuclear weapons.

“Not to mention the potential impact on the environment and climate, agriculture, migration and other direct and indirect effects,” Wan adds. Therefore prevention of such an event, the UN report states, remains the only truly effective humanitarian and public health approach.