Is Islamic State In Retreat? – OpEd

“The dawn of 2016,” wrote veteran Middle East observer, Con Coughlin, on December 30, 2015, “finds Islamic State (IS) very much on the defensive in both Iraq and Syria.” A good rule of thumb is not to count your chickens before they are hatched, but Coughlin produces evidence to justify his assessment. Does it stand up to close scrutiny?

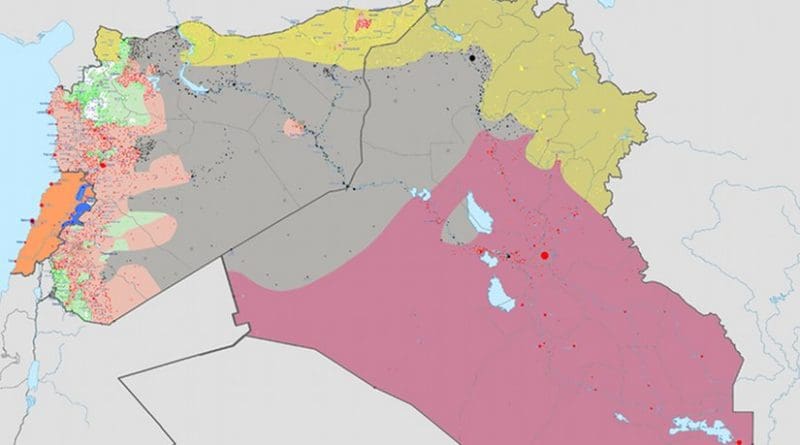

In May 2015, when IS fighters overwhelmed a far stronger and better equipped Iraqi army to capture Ramadi, the capital of Iraq’s western province of Anbar, the jihadi organization seemed unstoppable. IS’s progress towards a complete takeover of Iraq, and after it Syria, appeared almost inevitable. After all, Ramadi was only 60 miles from Iraq’s capital, Baghdad, and it seemed but a matter of time before Baghdad, too, would be in IS hands. But at the end of December, after days of fierce fighting, Iraqi security forces had gained control of central Ramadi. By the last day of 2015, a mop-up operation seemed all that was needed to recapture the city. IS resistance was stubborn, however, and pockets of fighters continued to hold out, frustrating coalition attempts to restore Ramadi to normality.

The defeat back in May of the Iraqi Security Forces (ISF) defending Ramadi, and its capture by IS, seems to have acted as a wake-up call to the US-led coalition. Indeed after the Ramadi loss US Defense Secretary, Ash Carter, is on the record as saying, rather hurtfully, that the Iraqi army had “no will to fight.” Clearly an essential preliminary to future successful operations against IS was to revitalize and re-energize the ISF.

This realization gave birth to what has been dubbed the coalition’s “Iraq First” policy. American and British military advisers concentrated on rebuilding the strength of the ISF to the point where it could provide the capable ground component, to be backed by coalition air cover, recognized by all as essential to reclaiming control of the country from Islamist extremists. The success at Ramadi seemed to demonstrate its effectiveness.

The government has designated the mostly Sunni city of Mosul, Iraq’s second city some 250 miles north of Baghdad, as the next target for Iraq’s armed forces. But with a population of around 1.5 million, Mosul presents a far more challenging target than Ramadi. Coalition commanders fear that the battle to recapture the city will involve intense street-to-street fighting. In any case, field commanders wonder whether it is worth attempting that operation before Falluja, lying between Ramadi and Baghdad, has been wrested from IS’s hands.

Falluja presents problems of its own. It is a religious and spiritual centre of Sunni Islam in Iraq, and the discrimination against Sunni Muslims exercised by former prime minister, Nuri al-Maliki, has left a bitter anti-government taste in some mouths. During the Maliki years some sort of deal was struck between Sunni militants in the city and IS, and in assaulting Falluja coalition forces might find themselves fighting not only IS, but local militants.

So the way forward is far from clear. In fact, the recapture of Ramadi may have raised expectations unrealistically. Iraq’s prime minister, Haider al-Abadi, speaking shortly after Ramadi had largely fallen into coalition hands, promised that by the end of 2016 all of Iraq would have been brought under the control of the country’s democratically elected government. A tall order, but doing just that – even if it cannot be achieved within a twelvemonth – is deemed essential if the US-led coalition is to stand any chance of defeating IS on the ground in neighboring Syria, where the situation is immensely more complex.

A good start has been made. On Christmas Day 2015, as one stage in the coalition’s march on IS-held areas in northern Syria, the US-backed coalition of rebels, the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), captured the key Tishrin dam on the Euphrates River from IS. The Tishrin supplies much of northern Syria with electricity. The SDF’s plan of campaign is to cut supply lines between IS strongholds in the north, in particular those between IS’s main city of Raqqa and its stronghold of Manbij.

The US military estimates that in the last six weeks of 2015 the SDF, bolstered by coalition air strikes, captured around 1,000 square kilometers of terrain from IS. In addition, coalition air strikes on the IS leadership had notched up a number of successes. One notable achievement was the strike that killed Charaffe al-Mouadan, a Syria-based IS member directly linked to Abdelhamid Abaaoud, believed to be the mastermind behind the coordinated bombings and shootings in Paris on November 13 which killed 130 people.

Mouadan is one of ten or more leading IS figures killed by targeted air strikes towards the end of 2015, among them so-called “Jihadi John”, the figure with the British accent who featured in the horrific “snuff” videos released by IS of the beheading of a succession of Western hostages.

On January 4, 2016, IS released a video on social media featuring a new masked gunman with a British accent. He directed the shooting at point-blank range of five men accused of spying for the UK, each shown “confessing”, before being killed. The Daily Telegraph revealed that an internal IS opposition movement – a group called “Raqqa is Being Slaughtered Silently” (RBSS) – had been undermining IS operations and providing information that led to the targeting and death of IS leaders by airstrikes, including Jihadi John. RBSS is an alliance of journalists and activists from Raqqa, the Syrian town that is IS’s de facto capital, and their mere existence demonstrates the internal dissensions that develop when an organization is under pressure or failing.

So obviously the ratcheting up of the coalition’s military action, its continuous pounding of IS positions from the air, its successes on the battlefield, the targeted assassination of IS’s leadership, the cutting of IS’s vital oil flows and its consequent loss of revenue – all are having an effect on the morale and the appeal of Islamic State. But, as US army Colonel Steve Warren, spokesman for the US-led coalition against the Islamic State, observed about IS: “It still has fangs.”

Perhaps the most apt assessment of the state of play at the start of 2016 are the words of Winston Churchill, uttered back in 1942, following the British success at El Alamein:

“This is not the end. It is not even the beginning of the end. But it is perhaps the end of the beginning.”