Will The Post-Mortem Begin In Poland? – Analysis

By Published by the Foreign Policy Research Institute

By Reggie Kramer*

(FPRI) — Among the many places where observers might have expected to hear the death knells of liberal democracy, Poland can’t have been high on the list. Yet, a number of developments in that country’s foreign policy and international outlook suggest that Poland is a candidate to play an important role in the world’s democratic recession.

First, some background information. For much of the 20th Century, Poland was deeply entrenched in Communist Eastern Europe—the Warsaw Pact, the Soviet bloc’s answer to NATO, was named after the Polish capital city. Somewhat ironically, Polish communism was overthrown by the forces of labor, in the form of the trade-union-turned-political-entity Solidarity. Throughout the 1990’s the country continued to reform, developing free elections, a market economy, and a civil society. In 2004, Poland joined the European Union (EU), having met its accession criteria. However, once praised for its democratic development, Poland has recently shown signs of slipping, leading some to question if its democracy was just for show.

In 2015, Poles voted the Law and Justice Party (PiS) into power. PiS currently controls more than half of the seats in both the Sejm (lower house) and Senate (upper house) of the Polish parliament, as well as the presidency. A party whose platform rests on nationalism and Catholic traditionalism, PiS supports constitutional amendments to concentrate power in the presidency, and weakening institutions that could challenge that power. Since coming to power, for example, PiS has taken steps towards delegitimizing the press and limiting its reach. It has been accused by Freedom House of meddling in the public media sphere and restricting independent and critical reporting at the same time as it works to control critical civil society organizations.

PiS leaders and politicians have made numerous remarks concerning a supposed “Islamic invasion” of Europe, have flatly refused to accept refugees, and have, by some accounts, stoked the flames of ultra-right extremism in Poland. Most recently, on July 22, the PiS-dominated legislature passed a series of controversial bills allowing the government to force Polish Supreme Court justices into retirement. However, in response to popular protests, Polish President and PiS member Andrzej Duda vetoed most of these measures, demonstrating that, despite its stranglehold on the government, PiS is not completely capable of enacting its agenda.

Though PiS’ Duda is the President and the party’s Beata Szydlo the Prime Minister, the power behind the government is Jaroslaw Kaczynski, one of the Party’s founders and a former prime minister himself. Writing in the New York Times, James Traub remarked, “neither allies nor enemies doubt that Kaczynski runs Poland.” Kaczynski holds no official office, but has been the leading force behind “deflecting Poland from the orbit of Western Europe and returning it to a past defined by family, church and home.” Kaczynski’s supporters are religious and economically disadvantaged—and they believe him when he says that they have not grown wealthier since the late 1980’s because the communists never really disappeared, but reinvented themselves as liberal democrats. In Poland, where the memory of hardships under communism looms large, this is a serious accusation.

PiS’ rise has the potential to threaten liberal democracy, not just in Poland, but across the world. The PiS government has positioned itself as one of the leaders of an illiberal bloc within the European Union, consisting mainly of Eastern and Central European countries, notably Hungary, Slovakia, and the Czech Republic. For the past few years, these countries have undermined the cohesion of the EU, one of the main bastions of liberal democracy, at precisely the time it needed to remain united. Most notably, Hungary and Poland publicly defied EU quotas regarding refugees, migrants, and asylum seekers. More recently months, Poland has grown from one dissenting state into the face of Eastern EU dissent—and, therefore, to some, the face of resistance to globalization.

The election of Emmanuel Macron, the newly installed President of France, has intensified the antagonism between Poland and Western Europe. During his campaign, Macron emphasized his pro-European credentials by calling for EU sanctions against Poland for failing to live up to ‘European values.’ In France, this enhanced Macron’s image as the “anti-Marine Le Pen,” his Eurosceptic, anti-immigrant opponent whose Front National party suggested an anti-EU alliance with PiS and Hungary’s ruling party. But, in Poland, it reinforced the perceptions that European ‘globalists’ are antagonistic towards, or at least ignorant of, Polish culture and traditions, and that the divide between Eastern and Western Europe is as much cultural as political, if not more. As one Polish far-right leader told Vice News:

Polish officials responded to Macron’s comments bitterly, and resolved to continue refusing refugees. There is some worry that Poland will continue to act out against EU orders, seeing itself as a bulwark of traditionalism against a wave of globalism. Should the EU sanction Poland and its allies in Hungary, Slovakia, and the Czech Republic—which seems more likely every week—it risks further antagonizing those states, driving the wedge between East and West within the EU even deeper, and, perhaps, causing the Union to stagnate or fragment. The European Union is one of the cornerstones of the liberal democratic order, and its decline could be devastating.

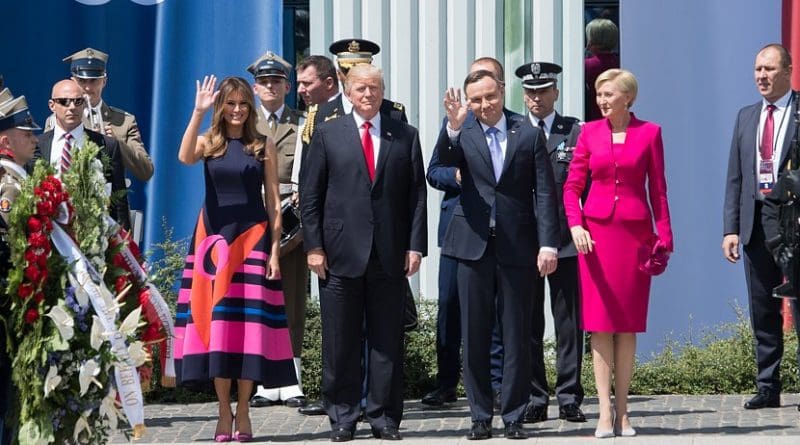

On another front as well, the current Polish government could pose a challenge to liberal democracy, in Poland and internationally. In US President Donald Trump, PiS has found a willing ally. Perhaps more importantly, however, Trump and PiS serve as echo chambers for one another. This was never more evident than during Trump’s visit to Poland in early July. For his Warsaw speech, PiS bussed in its supporters from across the country—the crowd size, estimated at 15,000, validated Trump’s message that Western civilization is threatened by immigration, bureaucracy, and the media. The President’s narrative corresponded perfectly with PiS’, bolstering its position domestically. This back and forth of affirmation of ideals strengthens both Trump and PiS as they go about pursuing domestic strategies that could threaten international democracy.

It is far too early to declare the democratic order a lost cause. Scholars disagree on whether or not democracy is even in recession. If it is, it is unlikely that Poland will be the state that makes or breaks the future of the liberal order. It’s also possible that some in PiS are having second thoughts about the government’s course. President Duda surprised many relieved observers in the West when he vetoed two of three laws aimed at weakening the judiciary and bringing judges more firmly under government control. Nevertheless, PiS, despite still being a minute player in the grand scheme of world affairs, has already made an impact on the cohesion of the EU and likely reinforced Donald Trump’s conviction that his current approach to politics—which does not include consideration for democracy abroad—is correct. PiS has presided over Poland’s democratic backsliding, and the effects have begun to cross national borders.

About the author:

*Reggie Kramer is a Research Intern with the Eurasia Program

Source:

This article was published by FPRI.