Exposed The Dark Side Of Coffee Cultivation In Uganda

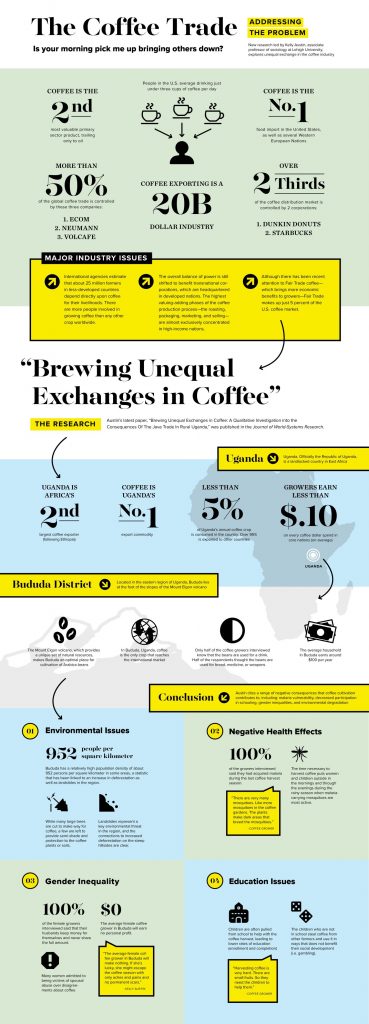

New research led by Kelly Austin, associate professor of sociology at Lehigh, explores unequal exchange in the coffee industry. She cites a range of negative consequences that coffee cultivation contributes to, including: malaria vulnerability, decreased participation in schooling, gender inequalities, and environmental degradation in Bududa, Uganda.

In Bududa, Uganda — Africa’s second largest coffee exporter following Ethiopia — the harvest typically runs from July through October. The season can extend beyond this, depending on the amount of rainfall, temperatures and the ripeness of the coffee cherries.

Located in the eastern region of Uganda, Bududa lies at the foot of the slopes of the Mount Elgon volcano, which provides a unique set of natural resources that make it an optimal place for cultivation of Arabica beans. The Arabica beans are considered higher quality in comparison to Robusta coffee, which is cultivated in the warmer, lower-lying regions in central Uganda.

For her research, Austin interviewed Bududa residents between the ages of 30 and 76, all of whom had been been involved in coffee cultivation for several years, with many of them learning to cultivate from childhood or adolescence. She drew on over 11 months of participant observation while living with a local family who grows coffee to supplement their income.

“Conducting interviews with coffee growers in the Bududa District is vital in unearthing the processes, trends and consequences of coffee cultivation in the region,” Austin wrote.

She notes that only around half of the coffee growers she interviewed knew that coffee is used most principally to make a drink. “Several of the respondents said that they thought coffee was used to make bread or medicine,” she said. “Even more shocking, another common response was that coffee was used to make weapons.”

The Coffee-Malaria Connection

During her research, Austin found that the coffee growers she interviewed noticed patterns in mosquito populations that bring their most significant threat to health: malaria.

“The fact that growers observe more intense populations of mosquitoes in their coffee gardens than in other gardens should come as no surprise, given that mosquitos thrive in wet areas with the right mix of sun and shade,” she said.

Every respondent she interviewed said they had acquired malaria, often multiple times, during the previous coffee harvest season. The time necessary to harvest coffee puts women and children outside in the mornings and through the evenings during the rainy season when malaria-carrying mosquitos are most active, Austin wrote in her study.

Lower Rates of Education Among Children

The rural district has a population of 211,683 people, with average household earnings around $100 per year. Most households in Bududa, according to The Republic of Uganda: Ministry of the Local Government, have more than six or seven children, with the average age of first birth for women being 14-16 years old.

Austin’s research points to the heightened labor requirements of coffee production, where children are often pulled from school to help with the harvest. She explains that children are not only pulled from school to harvest, but the children who aren’t in school steal coffee from other farmers.

One coffee grower she interviewed said, “There are many parents who use their kids to grow and harvest. Some parents tell their children not to go to school to help pick the coffee. Some kids who do not go to school [at all] sneak into the coffee gardens and steal the coffee. Then they use the money for gambling.”

Another grower, who is also the headmaster at a primary school commented, “When it is harvesting time, attendance goes down.”

Gender Inequalities

Gender inequalities facilitate unequal exchanges at the global level of the coffee exchange, as well as the micro levels, Austin explains in her latest paper, “Brewing Unequal Exchanges in Coffee: A Qualitative Investigation into the Consequences Of The Java Trade In Rural Uganda,” published in the Journal of World-Systems Research. Women rarely, if ever, see any profits from their time growing and harvesting coffee, reflecting the unequal exchanges between men and women within Bududa.

All of the women Austin interviewed and several men reported that the women principally grow, water, harvest and carry the coffee, but only the men are involved in the selling.

“It must be emphasized that in the end, the average male coffee grower in Bududa will only make less than two and a half cents on every cup of coffee sold in Northern markets. This is a gross injustice,” Austin wrote.

However she adds, “The average female coffee grower in Bududa will make nothing. If she’s lucky, she might escape the coffee season with only aches and pains, and no permanent scars.”

According to her findings, all of the women interviewed believe that coffee benefits the men of Bududa much more than the women.

A female coffee grower told Austin: “Many people fight because of coffee. Most times the men want to beat up their wives if they complain about him using the money to buy alcohol or cheat with other women.”

The Environmental Costs of Coffee Production

While coffee has been considered a shade crop with minimal impacts to forests, Austin said it is clear that many growers cut down large, native trees to make way for coffee plants. Only some trees are left to provide semi-shade and protection to the coffee plants.

She adds that many of the growers perceive native trees as competing with coffee plants for nutrients in Bududa.

Austin notes that deforestation and expanding cultivation sites on hillsides creates perfect conditions for landslides, with grave, lasting impacts for populations and the local ecology of the region.