Understanding The ‘New India’ And What It Means For Europe – Analysis

The relation with India is one of the key partnerships that Europe needs to strengthen. However, it must accept that a ‘new India’ is emerging.

By Alicia García-Herrero and Christin Ketels*

As the EU is reviewing its position in the global system, there is a growing recognition that the relationship with India will be of critical importance. India’s future trajectory will have a significant impact on the EU’s ability to achieve its global economic, political and climate change ambitions. This short paper aims to inform Europe’s approach towards India by outlining some of the core changes that have been shaping India over recent years. It documents the significant achievements India has made in addressing some of its traditional weaknesses and identifies the new type of challenges India is now facing. An effective EU policy approach has to recognise these new realities rather than being stuck in a view of the India of the past.

Analysis

India’s role for Europe’s future

There is a growing recognition across European capitals that Europe has to rebalance its economic relationships in the global economy, beyond its reliance on China, and in some ways also to complement the deep ties with the other advanced G7 member countries, especially with the US.

One of the key partnerships that Europe will need to strengthen is bound to be the one with India: the country is already the fifth-largest economy in the world and is poised to overtake Germany and Japan within this decade to become third behind the US and China. And it is a critical partner in achieving some of Europe’s strategic priorities. Firstly, India has a large and growing labour force to emerge as one of the future alternative suppliers of manufacturing goods, reducing the world’s (and Europe’s) reliance on China. Secondly, India has rapidly rising energy needs and thus has to be part of any realistic solution to the global climate challenge. Finally, India is –as the world’s most populous democracy in the heart of the rising Indio-Pacific region– a critical stabilising actor in an increasingly fragile geopolitical system.

Despite these reasons for seeing India as crucially important for Europe’s future, the starting point for many in European policy circles remains dominated by the India of the past. Views of India are shaped by impressions of poverty, weak infrastructure, coal-based energy systems, government regulations strangling private enterprise, trade barriers, food insecurity and strengths in back-office IT services, but few modern opportunities elsewhere.

As a result, Europe’s policy engagement with India also follows the patterns of the past: Trade policy is focused on access –visas for Indian workers against lower barriers for EU exports–. Climate change policy is focused on convincing India that climate change is real and that its use of coal is irresponsible. Economic development advice is focused on making it more like us, concentrating on market opening, institutional reform and skill upgrading. Security policy is focused on the moral argument to stand on the side of the West and against the worlds’ autocrats.

This approach to engaging with India is not likely to be successful. It fails to appreciate that a new India is emerging and has been for some time. The renewed trade discussions between the EU and India since May 2021 and the ongoing dialogue under the EU-India Strategic Partnership’s ‘Roadmap to 2025’ provide a window for the EU to implement such a new approach. This paper aims to motivate work on this approach by offering an initial perspective on the new India that is emerging.[1]

A look at the emerging ‘new India’

The emerging Indian powerhouse

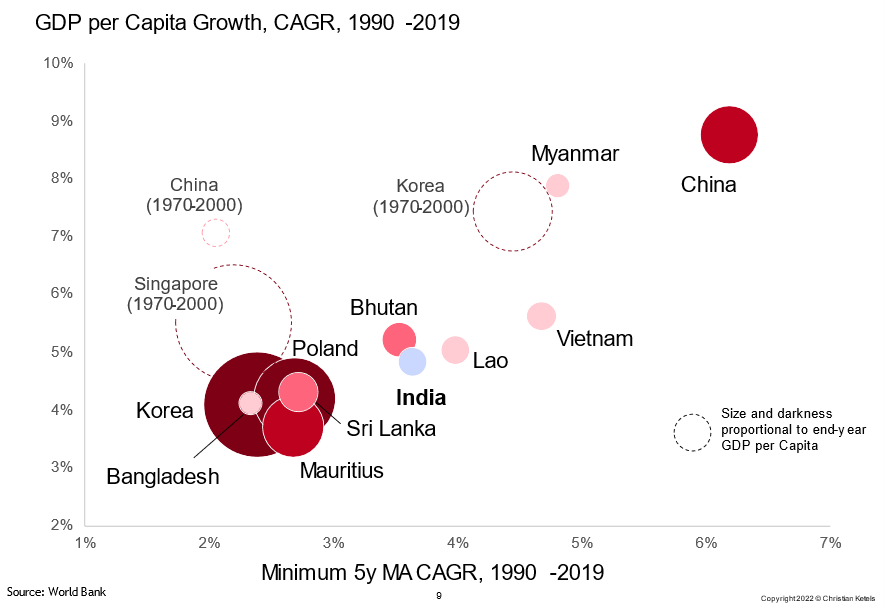

India has often been characterised as an economy of the future, but the reality is that India has already delivered one of the most impressive growth stories of the recent past. India is one of the 10 countries globally that have, over the last three decades up to the pandemic, achieved average annual prosperity growth above 3% while never falling below 2% CAGR for any five-year period.

Figure 1. Global leaders in sustained property growth, 1990-2019 (GDP per capita growth, CAGR)

The economy delivering this growth has changed in the process: it has become more open to the world from low initial levels. The share of Indian exports to GDP is now higher than for China or Japan, despite low dynamism since 2015. Between 2007 and 2019 the value of Indian exports has grown at a higher rate than China’s. Even FDI inflows as a percentage of GDP are now above China, and above both middle-income and lower-middle-income country averages.

India’s skill-intensive services now account for more than 20% of total value added in the Indian economy and dominate service trade. Skill- and capital-intensive manufacturing industries have grown as well, while labour-intensive manufacturing has stagnated as a share of national GDP. India has, for example, become a major production site for mobile phones. India now has more ‘Unicorn’ start-ups than the UK or Germany.

These changes are the result of a broad-based reform agenda. The state of physical infrastructure has improved significantly, especially in terms of electricity supply and to some degree also transport (roads and airports). India now has enough electricity generation capacity to meet its national demand. More than 50% of the increase in total generation capacity over the past five years has come from renewables, especially solar. India has made significant strides in digitalisation, driven by the ‘India stack’ of the Aadhaar personal identification numbers and the PMJDY programme, to massively increase financial inclusion via mobile-accessible bank accounts. Mobile penetration is above 80% and the price of mobile data one of the lowest globally.

The current Indian government has launched ambitious reforms on labour market liberalisation and tax simplification through a national Value-Added Tax (VAT). ‘Make in India’ has been launched as an overall agenda for FDI attraction, workforce skill development and the reduction of the administrative costs of doing business. Production-Linked Incentives (PLI) have been launched to encourage investments in manufacturing activities in specific sectors such as solar panels.

During COVID, India has conducted the world’s largest vaccination campaign, with more than 2 billion doses administered. The country has achieved self-reliance in agricultural products.

While India has achieved remarkable progress over recent years, it still retained some clear features of a developing economy: modest levels of productivity and prosperity, a young but on average poorly educated workforce, high levels of informality in the economy, a dominance of small, subsistence-oriented firms, and a large role of agriculture in the economy. The pandemic was a reminder of how close many Indians remain to poverty, and how inadequate the government system is in providing basic services at a time of crisis.[2]

The country is also struggling with many reminiscences of the ‘old’ socialist India. The financial system remains dominated by state-owned banks, and poor governance of credit markets has led to the emergence of a balance sheet problem that has weighed heavily on credit growth and investment in India. The judicial system is independent, but enforcement is ineffective, subject to improper influence and slow. Urbanisation is low and has dropped below the level of low-income countries. Labour mobilisation is low, and even falling, which matches the profile of the Arab world. India’s high levels of inequality are reminiscent of resource-dominated economies. Finally, India faces the large-scale environmental challenges that one would expect for an economy with rapid industrial growth.

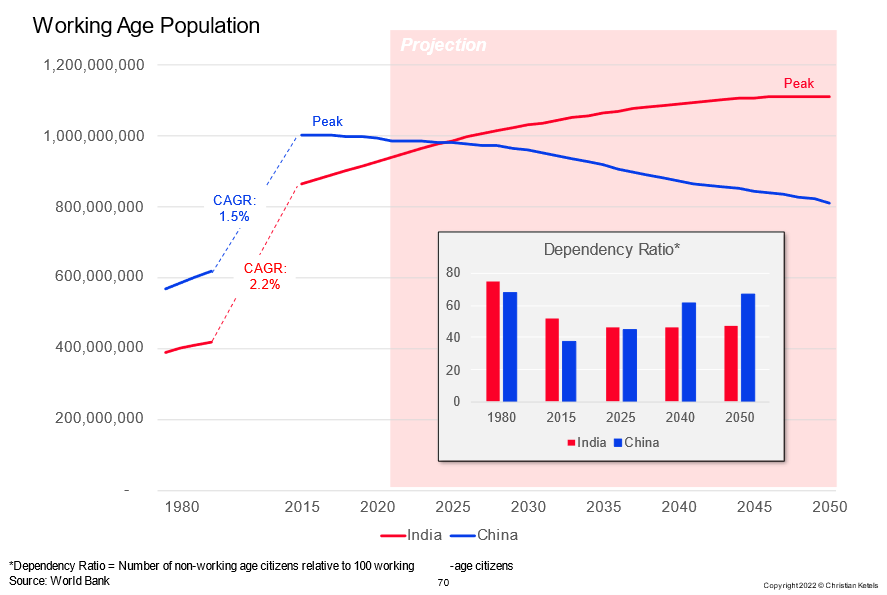

India’s biggest opportunity is its demographic profile, with a decades-long workforce growth, in stark contrast to China.

Figure 2. Working age population: India vs China

The hills India must climb

While India has seen real and impressive change, the reality the country is facing remains complex. Three challenges stand out, and a political wildcard is lurking in the background.

The first challenge is overcoming income inequality to achieve shared prosperity. Recent growth has to a large degree benefited those parts of society, the economy, and the country that are already competitive globally. Many others have found it hard to take advantage of the new opportunities.

The second challenge is creating enough jobs for a growing labour force. Recent growth has to a large degree reflected robust productivity growth amongst those in work. Job creation has been below 4 million in eight out of the last 10 pre-pandemic years, while on average more than 10 million Indians will be entering the labour market every year for the next decade.

The third challenge is enabling more effective policy implementation. India’s government has launched a wide range of ambitious policies. But the actual outcomes for citizens and companies fall short of intentions, often because markets remain highly distorted or because weak governance leads to poor delivery of public services. International competitiveness rankings fail to pick this up, focusing on the conditions relevant for the most advanced parts of India.

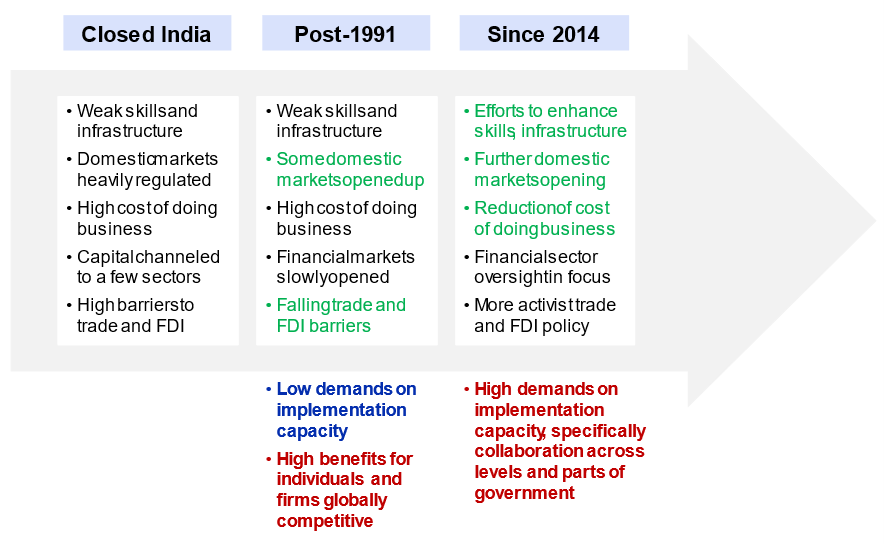

A key issue is understanding how the nature of India’s competitiveness challenges and the economic policy actions needed to address them has changed since the initial reforms of the early 1990s. The focus is now on strengthening the underlying assets and capabilities of the Indian economy; in short, enhancing rather than simply unlocking India’s competitiveness. This requires consistence over time and coordination across many different policy areas and parts of government. And this is where India’s government has struggled: in many areas it has the right intentions but has failed to find the right tools to gain traction across its large and heterogeneous territory.

Figure 3. The policy implementation challenge

In the next few years, robust growth is almost a given because of low-hanging fruits such as population growth and fast urbanisation. In fact, India tops the global growth rankings for 2023 in the latest IMF World Economic Outlook. But moving beyond will require step changes in policy and policy-making structures, which have not yet been put in place. In that regard, India’s quest for strategic alliances, especially to secure the foreign direct investment needed to create productive jobs is key. Developing a strong manufacturing sector with the same foreign capital seems like a logical way forward, based on China’s experience.

What it means for Europe

Europe can have a stake in India’s success. An India that leverages its potential is very much in Europe’s interest. An economically successful India will be a stabilising factor in a fractured geopolitical world, and an alternative supplier of many goods and services. An India that increases its supply of affordable energy while reducing its CO2 footprint will be a critical pillar of any global strategy to realise its COP26 commitments. Eventually, a growing India will also play an increasing role as a market.

Against such a backdrop, Europe should pursue policies that can help India succeed. Too often, however, the approach towards India is driven by a narrow view on what type of short-term benefits can be extracted from the EU-India relationship. What is needed instead is an approach that looks at opportunities for Europe to enable and engage with the development path that India is upon.

Trade policy is a key example. The focus of the trade negotiations is based on market access and, as in many such instances, it will be a hard bargain between two parties that perceive giving market access as a price to pay. A more realistic approach would focus on enabling European companies to play a role in India’s ambitions to build up stronger manufacturing capabilities. This is clearly in India’s interest: the whole Make in India project is aimed at achieving such outcomes. But it will also provide European firms with opportunities to leverage their technology and secure jobs in European value chains linked to these new production lines. And it will provide European manufacturing companies with additional options to diversify their supply chains away from China. India might be a less established export platform than countries like Vietnam, but it provides the added benefit of much larger domestic market potential.

Climate change is another key area. The focus on getting India to adopt more stringent CO2 reduction commitments appears based on the view that India simply does not understand the long-term costs of its energy mix to itself and the global community.

A more realistic approach would recognise that in India solar energy is already cheaper than coal-based energy and focus on how Europe can enable India to respond. The challenge is overcoming highly distorted legacy structures in the Indian energy market, dependence on China as the dominant supplier of solar and wind energy generation equipment, and the complexity of local planning and regulatory approval processes to get investments done in a timely fashion. It is also the need to create an energy system that provides affordable energy at all times of the day and to deal with coal-based regional economies –both challenges that India shares with the EU–.

Europe’s interest in India is clearly growing, with trade, investment and climate as key areas on which to focus. But this interest will only lead to an effective and mutually beneficial engagement if Europe’s leaders understand the ‘new India’ with which they are partnering and design European policies accordingly.

Conclusions

The EU has a stake in India being successful in the future. Without an India that achieves socially and environmentally sustainable growth, the EU will face a global context that is far more treacherous in terms of climate change, geopolitical tension and global economic imbalances. While this critical role of India is increasingly recognised, the EUs policy approach towards it too often appears to be shaped by a view of India that is outdated. It is still viewed as a country of widespread poverty and poor infrastructure, unwilling to recognise the impact of a coal-based energy production on climate change. India has, in fact, achieved one of the most impressive growth trajectories globally over the past few decades. It produces enough food to feed itself, enough electricity to serve its domestic demand, has invested significantly in infrastructure and has digitalised a wide range of public functions. Many challenges remain for India to achieve its highest ambitions, but these now have more to do with institutional weaknesses and still highly distorted market structures than a simple lack of resources or technology. India would benefit significantly from the EU’s partnership in these areas. But it will react allergically to actions by the EU that it perceives as reflecting an old ‘condescending’ or even ‘colonial’ mindset.

*About the authors:

- Alicia García Herrero was Senior Research Fellow at the Elcano Royal Institute. Chief Economist for Asia Pacific at NATIXIS, she also serves as Senior Fellow at the European think-tank Bruegel and as a non-resident research fellow at the Emerging Market Research Institute (Johnson Cornell University).

- Christian Ketels, Harvard Business School Faculty

Source: This article was published by Elcano Royal Institute

[1] For the deeper analysis that this blog post is based on see Competitiveness Roadmap For India@100 – EAC-PM (eacpm.gov.in).

[2] Bhalla, Surjit, Karan Bhasin & Arvind Virmani (2022), ‘Pandemic, poverty, and inequality: evidence from India’, IMF Working Paper, nr 2022/069, IMF, Washington DC.