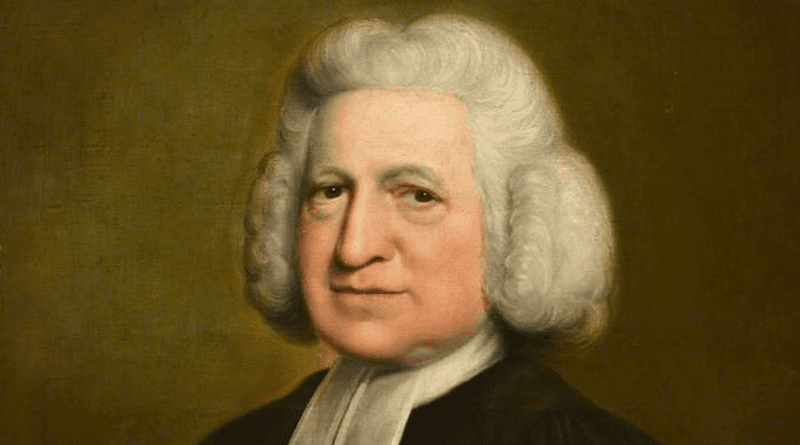

Charles Wesley: Hymn Writer Of The Evangelical Revival – OpEd

By Richard Turnbull

The less-famous brother of John Wesley, the founder of the Methodist movement, Charles nevertheless left a lasting legacy of rich hymnody that churches around the world enjoy to this day.

The evangelical revival we have been revisiting not only left a legacy of Christians and churches renewed and empowered but also a devotional spirituality embedded in hymn and song. Charles Wesley (1707–1788) worked tirelessly alongside his elder brother John as evangelist and pastor. He is the less studied of the Wesleys and yet, in some ways, better known, principally through his extensive corpus of hymns, many of which we sing today. The poetry of his written word has proved an extraordinary gift to the global church. And so we continue our story of the 18th-century revival in Britain through the eyes of the younger Wesley.

Charles was born on December 18, 1707, two months premature, in Epworth rectory in Lincolnshire—the same place where John was born just over four years earlier and where their father exercised his pastoral ministry—the penultimate child of Samuel and Susanna (19 in all, 10 surviving to maturity). Readers of the previous article on John Wesley will recall the disastrous fire in the rectory in 1709, one significant in the providential history written around John. Charles, too, as a baby was rescued from the fire, but his preservation has not received the same pious treatment. In 1716, age 8, Charles left for Westminster School in London and then, in 1726, entered Christ Church, Oxford. He described himself, in his first year, as “lost in diversions,” with his social life gaining the upper hand over piety. Like John, now a fellow at Lincoln College, he slowly awoke from his spiritual slumber and sought the reformation of his spiritual life. He was instrumental in forming and leading the “Holy Club,” through study, taking the sacrament weekly, and engaging in good works—indeed, leading the group when John was absent undertaking pastoral work in their father’s parish. Charles spent 1736–1738 in Georgia with John, and upon their return both underwent the classic evangelical conversion experience. Charles recorded his own experience on May 21, 1738 (three days before John Wesley’s conversion), in his Journal, describing the Spirit of God “chasing away my unbelief.”

Charles Wesley’s personal life could not have been more unlike his elder brother’s, however. His one serious romance, with Sarah Gwynne (commonly known as Sally), led to marriage. Sally had a good Methodist pedigree, her father a convert of the Welsh evangelist, Howell Harris. They met in 1747 while Charles was preaching in Wales. There was an engagement of heart and mind, a spiritual as well as romantic unity. They married on April 8, 1749, Charles aged 41, Sally, 19 years his junior, with John presiding at the occasion. Charles’ marriage, unlike John’s, proved a model of love, stability, and happiness; also contrary to the practice of the elder Wesley, Charles traveled much less in ministry after his marriage, preferring a settled home life.

Charles is an example of the inherent tensions in early Methodism between the expectations of the Church of England (respecting parish boundaries and the ministry of the parish church) and the itinerant enthusiasm for proclaiming the gospel outdoors and empowering lay preachers. Both Charles and John pleaded loyalty to the Church of England, yet Charles, too, adopted the classic Methodist approaches, preaching in the open air for the first time in May 1739, merely a month after John. Charles, though, was more reluctant to preach in another parish unless he had been excluded from his own. In 1743 he referred to his “inviolable attachment to the Church of England.” Charles recognized that the lay preachers who had emerged as revival spread were mightily used by God but urged caution against a public ministry for the these laypeople, preferring that their work remain within the religious societies that formed the bedrock of much of early Methodism when it was still a revival movement within the Church of England proper.

Up to the point of Charles’ marriage, the two brothers worked in concert, in ministry journeys and pastoral care. However, in the early 1750s Charles became more skeptical about the character of the lay preachers, not least following some scandals, and there was also some dispute with John over power and authority. Charles was concerned that John was pressing ahead toward separation from the established church and performing his own ordinations, though the 1755 Methodist Conference declared that separation, although lawful, was not expedient. The tensions continued and, whether it was these or the claims of marriage and family, Charles’ extended ministry tour in 1756 was his last, after which he confined his work to the areas around London and Bristol.

Charles Wesley’s hymns were a work of poetic genius, although they were not devoid of polemical intent. We should, first of all, take a step back and consider the place of hymnody in the spirituality and history of the evangelical revival.

Hymns did not originate with the evangelical revival but were invested with a new significance. The idea of a personal encounter, an experiential relationship with God, which the Wesleys had observed in the Moravian Christians they had met traveling to Georgia, found expression in the congregational hymns.

Singing in most churches—and all churches that were part of the Church of England—in the 17th and 18th centuries consisted only of Psalms, with England more dependent on the Genevan Reformed tradition than was German Lutheranism, in which congregational singing was more the norm. The singing was led by a parish clerk (or precentor) who would sing a line that would be repeated by the assembled musicians in the gallery (known as “lining-out”). The congregation listened passively. The gallery musicians, the village band and singers, rarely approached their task spiritually. They were often late, the worse for drink, usually hiding behind the gallery curtain except for their own set part, reading, playing cards, and engaging in gossip during the sermon. Hymns as we know them today were slow to catch on—although increasingly embraced by those influenced by the revival—and remained, technically at least, illegal in the Church of England until a court ruling in 1819.

Charles Wesley’s hymns are masterpieces of poetic communication. He wrote somewhere between 4,000 and 7,000 of them, many still extant. He was, of course, not the only hymn writer of the time; for example, the poet William Cowper and the rector of Olney in Buckinghamshire, John Newton (“Amazing Grace”), formed a partnership in the more Calvinist part of the revival. Isaac Watts is a prime example outside the Church of England (“When I Survey the Wondrous Cross”). Charles Wesley’s hymns, however, continue to form a significant aspect of evangelical piety. Some of Wesley’s grand, expansive hymns (for example, “O for a Thousand Tongues”) were written specifically for the open-air rallies and preaching undertaken by the Wesley brothers. Thousands of miners gathering at Kingswood, near Bristol, singing out “O for a thousand tongues to sing, my great redeemer’s praise,” must surely have stirred the heart.

Unsurprisingly, the theme of the new birth features in many of Wesley’s hymns. Examples include “he breaks the power of cancelled sin, he sets the prisoner free,” “new life the dead receive,” and “Jesus! the name to sinners dear, the name to sinners given.”

Charles Wesley’s hymns could also fall into romantic and esoteric fantasy—his brother John described some of them as “namby-pambical.” The main contested area in early evangelical hymnody was whether to celebrate an atonement won by Jesus on the cross for all (the Wesleys) or limited strictly to an elect (relatively) few chosen by God (Whitefield, Newton). There is no doubting where Charles Wesley stood on this matter, as his hymns ring out with cries of the vastness and availability of God’s grace and love. One example here is from “And Can It Be,” where we sing “so free, so infinite his grace” and “tis mercy all, immense and free.” Hymnody, inspiring and uniting on the one hand, was by no means free from controversial doctrinal content on the other.

Declaring, like John, that he lived and died a member of the Church of England, Charles asked to be buried in the churchyard of Marylebone parish church. John, however, was buried next to a Methodist chapel. Charles died, aged 80, in 1788, and more than 30 years later, his beloved wife, Sally, was buried alongside him.

How might we assess Charles Wesley? As an unsung hero who labored in the revival vineyard alongside his history-making famous brother? As a key participant in the formation and development of Methodism? Perhaps more enduringly, as a Christian poet—an unrivalled hymn writer whose legacy will last as long as does the Church. For that alone, he deserves our thanks.

*About the author: Rev. Dr. Richard Turnbull is the director of the Centre for Enterprise, Markets and Ethics and a trustee of the Christian Institute. He holds a degree in Economics and Accounting and spent over eight years as a Chartered Accountant with Ernst and Young and served as the youngest ever member of the Press Council. Richard also holds a first class honours degree in Theology and PhD in Theology from the University of Durham. He was ordained into the ministry of the Church of England in 1994. Richard served in the pastoral ministry for over 10 years. He was also for 7 years the Principal of Wycliffe Hall, Oxford. He has authored several books, is a Fellow of the Royal Historical Society and a visiting Professor at St Mary’s University, Twickenham.

Source: This article was published by the Acton Institute