In Anticipation Of Counteroffensive, Russia Moves Thousands Of People From Homes In Southern Ukraine

By RFE RL

By Oleksandr Yankovskiy and Olena Badyuk

(RFE/RL) — “In the beginning, numerous children were taken away, and the parents who sent their kids to schools and kindergartens were receiving threats,” a resident of Polohy, a Russian-occupied city in Ukraine’s southern Zaporizhzhya region, told RFE/RL on condition of anonymity.

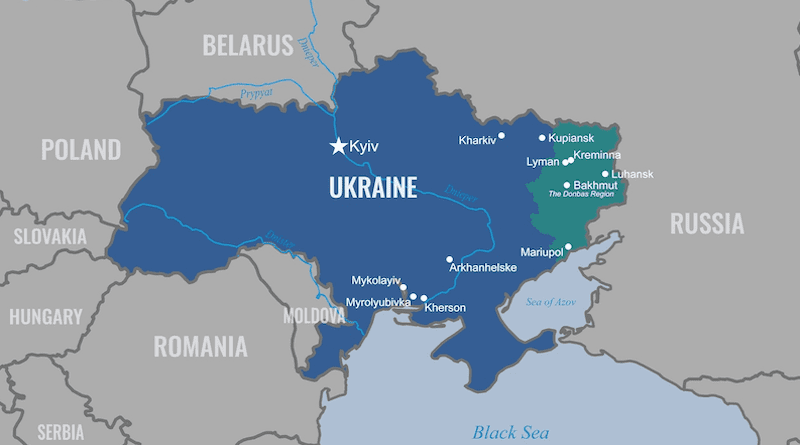

As Ukraine gears up for a long-anticipated counteroffensive, officials displaced from the Zaporizhzhya and Kherson regions say Russia is forcibly removing civilians from occupied towns and settlements close to the front line in the south. Reports of what Russia calls evacuations are piling up.

The evacuation of 18 settlements in the occupied part of the Zaporizhzhya region was announced by the Russian-installed administrator, Yevhen Balytskiy, on May 5. In a video message, he said the decision is a “necessary security measure” due to the intensification of shelling and assured that “there is no panic.”

Two days later, Balytskiy said that more than 1,600 people, including 660 children, had been moved to Berdyansk, a Russian-occupied port city farther south, on the Sea of Azov. He also promised a payment of 10,000 Russian rubles ($130) to those leaving.

Another representative of the occupation authorities in the Zaporizhzhya region, Volodymyr Rohov, said in his Telegram channel that the so-called “evacuation” was voluntary. He also said that the list of settlements from which the local population will be evacuated may expand.

The anonymous resident of Polohy, who didn’t want her name published due to security concerns, said the children who were forced to leave Polohy — some of them accompanied by their mothers, some not — were promised to be settled in a vacation camp in Berdyansk.

“But not everyone got accommodated because these camps are filled with occupiers and [Russian] military personnel,” she told News of Azov, a project of RFE/RL’s Ukrainian Service that covers the Sea of Azov coastal area of Ukraine.

According to her testimony, some people were eventually settled in dire conditions, without the provision of food that had been promised, and others were taken to the city of Rostov-on-Don and other places in Russia.

In addition to children, the woman said that members of the occupation authorities and people who collaborated with them had also left Polohy, as well as some teachers and doctors.

Polohy is on the front line south of Hulyaypole and southeast of Orikhiv, both

of which are controlled by Ukraine. The resident said that while some people were leaving the city, Russian military personnel were bringing in more equipment, building fortifications, and digging trenches — signs of preparations for the expected counteroffensive.

“They have been dismantling the locomotive depot for several days. They take out the railway cars, cut them into pieces, and put that on their trucks and take it someplace in the fields, where they are digging them in to create makeshift bunkers,” the woman said.

She said that people staying in Polohy were stockpiling water and food in anticipation of the counteroffensive of the Ukrainian Army while the Russian military is trying to intimidate them.

Given the ongoing hostilities and Russia’s occupation of Ukrainian territory, RFE/RL was unable to obtain official confirmation of this testimony or independently verify it.

But statements by Ukrainian officials displaced from occupied cities and towns in the Zaporozhizhya and Kherson regions suggest that a substantial campaign of forced evacuations has begun.

‘Forcibly Taking Children’

The displaced mayor of Polohy, Yuriy Konovalenko, said that residents of the city and surrounding district who have children began to receive messages about the so-called evacuation of mothers with children to occupied Berdyansk. All those who decide to stay must put their refusal in writing, he said.

The displaced chief of the Ukrainian military administration of the nearby Russian-controlled city of Tokmak, Oleksandr Chub, said children were ordered to come to schools with their belongings and documents. Schools, shops, the local market, pharmacies, and utility companies were closed that day, and doctors were not allowed to go home, he added.

Ivan Fedorov, the displaced mayor of Melitopol, a large Russian-held city in the Zaporizhzhya region, said the occupation authorities were planning to move about 70,000 residents from settlements along the front line. He said the occupation authorities were “forcibly taking children away” and that humanitarian conditions in some settlements had deteriorated, with medicines and other goods in short supply.

“They are hiding behind [the claim that they are] taking care of civilians, but in reality, in anticipation of a counteroffensive, they want to set up military bases there,” Fedorov said.

The head of the Berdyansk city military administration, Viktoria Halitsyna, confirmed that the occupation authorities’ representatives, collaborators, and children from the Zaporizhzhya region are being taken to Berdyansk.

She said that Russian military personnel have been arriving in the city along with civilians, accusing the soldiers of using them “as a human shield” for their military movements.

Occupation authorities have also announced evacuations from Enerhodar, the city on the south bank of the Dnieper River where workers from the nearby Russian-held Zaporizhzhya Nuclear Power Plant live.

On May 6, International Atomic Energy Agency Director-General Rafael Grossi said IAEA experts at the plant had “received information that the announced evacuation” of Enerhodar residents had started, according to an IAEA news release.

The IAEA experts were “closely monitoring the situation for any potential impact on nuclear safety and security,” it said.

“The general situation in the area near the Zaporizhzhya Nuclear Power Plant is becoming increasingly unpredictable and potentially dangerous. I’m extremely concerned about the very real nuclear safety and security risks facing the plant,” the news release quoted Grossi as saying.

In a comment to News of Azov, the displaced mayor of Enerhodar, Dmytro Orlov, said that people were being moved out and that goods and services were getting scarce.

“They took out the equipment from the medical-sanitary unit, computer equipment, documentation, and the passport office, which they had on the premises of the plant; they took it all about a week ago. The Internet connection is not working anymore, and grocery stores and pharmacies are closed. There is a rush to buy food and basic necessities. Gas stations and ATMs are also empty,” Orlov said.

Most of the locals who have been cooperating with the Russian occupation forces left Enerhodar even earlier, he said.

Meanwhile, reports said that in the occupied part of the Kherson region, Russian troops have been moving into the homes of locals who have left the area. According to the Center for National Resistance, a Ukrainian state agency monitoring the occupied territories, a unit of the Russian National Guard settled in the homes of Ukrainians who had been evacuated earlier from the town of Oleshky by the occupation authorities.

The displaced mayor of Oleshky, Yevhen Ryshchuk, claimed that panic was spreading among the Russian military personnel stationed in the town.

“We see that they have become more active, documents are being checked at checkpoints, more stuff is being taken away,” Ryshchuk told News of Azov. “There are constant rotations, and each new rotation wants to steal something, to take something away. It is a fact they are in a great panic that there will soon be a counteroffensive by the Ukrainian Army.”

Preparation For The ‘Goodwill Gesture’

Oleksandr Kovalenko, a military and political observer of the Information Resistance group, a Ukrainian NGO countering Russian propaganda, told News of Azov that Russian forces in the occupied part of the Zaporizhzhya region were conducting the “first phase of preparation” for the “goodwill gesture” — meaning a withdrawal in the face of a counteroffensive.

The phrase became popular in Ukraine following counteroffensives last year in which Ukrainian forces regained control over swaths of land in the east and south, including Kherson, the only regional capital that Russian forces had taken since the large-scale invasion in February 2022. In some cases, the Russian military said it was pulling back as a gesture of goodwill.

“In the first phase, they are taking medical personnel and the wounded out of the occupied territories, taking out medical equipment, that is, looting all hospitals, even pharmacies — taking out the medicines that are there,” Kovalenko said.

He predicted that Russia would soon start withdrawing artillery in case its troops are forced to retreat quickly, and then removing military communications systems.

“That will mean that the goodwill gesture will take place in one or two weeks,” he said.

With expectations of a major spring counteroffensive making headlines around the world for weeks, Ukrainian officials have been trying to play down expectations. But Kovalenko said he believes the public discussion about a counteroffensive is demoralizing for Russian troops.

“Everyone is talking about it; everyone is coming up with theories about it. But no one knows 100 percent how it will happen, whether it will follow the scenario that many people assume, or whether it will be something so unique that no one is ready for it. That’s why the Russians, I would say, are panicking for real,” he said.

Written by Aleksander Palikot in Kyiv based on reporting by Oleksandr Yankovskiy and Olena Badyuk of RFE/RL’s Crimea.Realities and News of Azov.

- Oleksandr Yankovskiy is a correspondent for RFE/RL’s Ukrainian Service. Originally from Crimea, Yankovskiy has worked as the editor in chief and presenter of the Crimea.Realities TV and radio projects. Since 2021, he has been a presenter for The News of Azov Region project.

- Olena Badyuk is a correspondent for RFE/RL’s Crimea.Realities and The News of Azov Region project.