Is Russia Determined To Stir Up Inter-Zhuz Confrontation In Kazakhstan And Divide It Into Several States? – Analysis

At first glance, Moscow appears to be having great enthusiasm for the future of the Eurasian Economic Union, whose role, to hear the Russian officials tell it, is rapidly growing amid external pressures. But this whole thing just sounds like wishful thinking. After all that has happened, there’s actually not much left to boast with. Actually, Moscow is certainly well aware that the prospects of the EEU, dominated by Russia whose oil exports to most countries of the Western World are now subject to embargo that should be set by 2023 at the latest and whose government does not control production of oil on the territory of its ally, Kazakhstan, and that country’s exports to the EU market, do not look promising. This is no discovery. It’s about things that are self-evident. Under these conditions, the Kremlin, should it intend to decisively turn the tide in its favor, can only set hopes on one thing – reaching the capacity of, in the words of Nina Khrushcheva, a professor of international affairs at the New School in New York, ‘having a political and economic say in Kazakhstan’.

Moscow can achieve this by resuming the political and economic initiatives that it had been promoting in the mid-1980s and had abandoned a few years later due to the collapse of the USSR. As they say, the new is a well-forgotten old. Moscow and the Kremlin became imbued with the idea that the Russian-Soviet state’s material and political power would grow by Western Kazakhstan, as well as its oil and gas reserves, in the early 1980s, after the discovery of the Tengiz oil field and the Karachaganak gas condensate field. By then, the peak period for oil-well production was almost over at the huge Samotlor field that bankrolled the Soviet Union for many years.

After having discovered Tengiz and Karachaganak and seen the possibilities of making vast discoveries of petroleum on the north-eastern continental shelf of the Caspian Sea adjacent to Kazakhstan, Moscow began developing Western Kazakhstan into a new basis for its oil and gas industry. By the mid-1980s, a specially elaborated State plan to support the development of the oil and gas complex in Western Kazakhstan was adopted and set into motion. 3 billion Soviet rubles were allocated by the USSR government to put it into practice. That was a huge amount of money in those days.

At that same time, Moscow undertook comprehensive studies on the situation in Kazakhstan which revealed, among other things, that the predominantly ethnic Kazakh working class had been developed in just one sector of economy. Namely, on the base of the oil and gas industry in Western Kazakhstan. (It would be appropriate to recall here that the USSR considered itself a state where power belonged to the workers.)

And then, what the Kremlin, bearing in mind the growing importance of that region in the USSR as a whole and the fact that it is in that region that the ethnic Kazakh working class is most concentrated, must have decided is that people from there should be appointed to leading and decision-making positions in Kazakhstan.

As a result of the discord that occurred in the mid-1980s among those at the highest echelons of power in Kazakhstan and the subsequent reshuffling of republican leadership, the Junior (Western) zhuz elites took hold of the most advantageous position. Then, three out of the five highest republican leadership posts were occupied by people from Atyrau, the most important oil-producing region of the republic where Kazakhstan’s giant Kashagan and Tengiz fields are located, represented by Salamat Mukashev (Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the Kazakh SSR); Sagidulla Kubashev (second Secretary of the Central Committee of the Kazakh Communist Party) and Zakash Kamalidenov (Secretary for ideological work of the Central Committee of the Kazakh Communist Party); the two others, by Gennady Kolbin (first Secretary of the Central Committee of the Kazakh Communist Party), a Kremlin’s representative, and Nursultan Nazarbayev, (Chairman of the Council of Ministers of the Kazakh SSR), a representative from South Kazakhstan (the Senior zhuz).

All three of the above-named people from the Junior (Western) zhuz were the representatives of the Baiuly, the most populous one of its three tribal groups. Two of them – Salamat Mukashev and Zakash Kamalidenov – were oilmen by trade, and the third one – Sagidulla Kubashev – was a professional Communist party functionary. By the start of the 1990s, when the Kremlin began to rapidly lose authority and political influence in the ethnic (non-Russian) republics, the group of Western Kazakhs, who had previously been appointed to leadership positions in Kazakhstan, was ousted from key posts. Implementation of such measures had been greatly facilitated by the practical impossibility for the Junior zhuz elites’ to count on any significant social or political support in Almaty, which then was the Kazakh capital, and the south of Kazakhstan.

All of the political heavyweights, which had been part of that group, were sent into retirement. By that time, Moscow recalled Gennady Kolbin, who had been sent some years earlier there by the Kremlin to be the first Secretary of the Central Committee of the Kazakh Communist Party, and promoted Nursultan Nazarbayev to the position of the de facto supreme leader of Kazakhstan. This effectively meant returning the reins of power in Kazakhstan to the Senior (Southern) zhuz elites after a brief hiatus.

Before the advent of Kolbin, Kazakhstan was for over two decades ruled by Dinmukhamed Kunayev, Southern Kazakhs’ previous representative in this position. Not long thereafter, the Soviet Union disintegrated. And Kazakhstan became independent. Then it turned out that those huge oil and gas fields which had cost Moscow a lot of efforts and money were no longer within the Russian national borders. In 1992, the then head of the Russian government, Egor Gaidar, speaking on television, told the Russians this: we no longer have those huge opportunities that we had before, because the Samotlor oil field is considered to be nearly depleted. Western Kazakhstan was found to have been beyond Russia’s reach.

As Moscow was recovering from yet another turmoil that had led to the collapse of the Soviet power, West Kazakhstan’s largest hydrocarbon deposits quickly ended up being used by the Western oil companies. Now, that is history. It was what it was. However, Moscow now seems to be willing to throw things back to conditions we until quite recently thought to have been leave far behind.

One might say, this all began with Russia’s recognition of the DNR and LNR independence on February 21, 2022, which turned out to be only a prelude to its all-out invasion of Ukraine a few days later in order to ‘denazify’ and ‘demilitarize’ this sovereign state. In other words, it was not about the hidden or explicit support by the Russians of some separatist region in one of the post-Soviet nations, but about in effect a declaration of war against such a CIS country.

But the most important thing is that then official Moscow or, to be more precise, the Kremlin effectively withdrew its signature under the Alma-Ata Protocols of December 15, 1991, according to which the CIS countries ‘acknowledge and respect each other’s territorial integrity and the inviolability of existing borders’.

Thus, the post-Soviet countries have entered a new stage of development. But so far none of them, except for Ukraine, seem to have felt any changes yet. However, that does not change the fact that as a result of the Russian-Ukrainian war, official Moscow, among other things, relieved its commitment ‘to acknowledge and respect other countries territorial integrity and the inviolability of existing borders’ within the post-Soviet space.

So now there is reason to believe that Moscow may do much to get what it wants. In the current situation, becoming increasingly aggravated by the results of Brussels’ decision to ban most Russian oil exports to the EU, Russia’s biggest interest obviously is in establishing, in one way or another, its control over the growing flows of oil, running from Western Kazakhstan to Europe.

Views just recently were expressed among the Russian and Western experts that Kazakhstan is far more important to the Russian Federation than Ukraine, Belarus and Moldova combined, as ‘it is kind of like Ukraine presented in a concentrated form’, and that the Central Asian country is ‘only place Russia could expand without disaster’. A few months ago, they thought that the situation must be regarded as such.

And such a vision has not lost its significance in the light of further developments. On the contrary, it now appears to be even more believable. Although the issue under consideration is not being very actively discussed, now many already understand that within the context of the open conflict against the West in which Russia has already been involved, it needs getting control, in some form, over Western Kazakhstan. It needs this in order to, if not win, then at least to survive and avoid a total fiasco which may be followed by the collapse of the Russian Federation itself. It needs to get such control not only over energy resources, but also over the entire region. Only then Moscow would be able to make it necessary for the major multi-national energy corporations, developing the largest Kazakhstani oil and gas fields, and hence, the so-called ‘collective West’ as a whole, to seek a compromise with the Russian Federation. There doesn’t seem to be any other tricks up the Kremlin’s sleeves with the help of which it could hope to reverse the current situation that is going quite badly for Moscow. Russia has two potentially important levers to influence its Central Asian neighbor in this regard. The first of them is relevant to the issue of water shortage in Western Kazakhstan, and the second to a situation in which, according to Russian media, ‘the country is commanded by the Senior (Southern) zhuz, whereas the people of the Junior (Western) zhuz are working’. Both of these factors are now being actualized by the Russian side.

Western Kazakhstan is the most arid region in the Kazakh country. Under the Soviet Union’s centrally planned economy, Moscow, setting for itself the target to develop Western Kazakhstan into a new basis for its oil and gas industry and expecting a significant increase in demand for water there, envisaged measures to address problems that might arise in this regard. So, firstly, there was a plan to build a 1285 kilometer water pipeline from the Kigach River (part of the Volga Delta) to the oil-rich Atyrau and Mangystau provinces in western Kazakhstan. It was meant to supply drinking and technical water from the Volga River to the population in these two provinces and to the oil fields located in their territories. And, secondly, there were plans to improve the water supply situation in Western Kazakhstan through the projects of inter-basin transfer of Volga waters to Ural basin.

The first of those ideas soon became a reality. The Astrakhan – Mangyshlak main water supply pipeline was completed and commissioned in 1988, i.e. shortly before the collapse of the Soviet Union. It must now be difficult, if not impossible to envision not only productive activities, but also human existence and life without this water conduit in the Atyrau and Mangystau provinces which are the only two donor provinces in Kazakhstan. The second idea remained on paper, because after the collapse of the Soviet Union, Moscow no longer had any interest in its implementation.

But more than that, Russia is now greatly contributing, or has contributed, to further worsening of the water crisis in Western Kazakhstan. But more than that, Russia is now greatly contributing, or has contributed, to further worsening of the water crisis in Western Kazakhstan by reducing of water discharges into Ural from the reservoirs in the upper reaches of this river. It is not known for certain whether this is due to some intent. But here is just how Alexander Yalfimov, а writer, has characterized the situation: “As for the Ural River, it’s a very sore subject. What could be said about what is happening? Why did it, for no reason, begin to grow catastrophically shallow? Let’s take this issue very seriously. The Ural is just dying. On the territory of Bashkiria, there are – in layman’s terms – three partitioning facilities that do not let water through. As a result, Bashkiria sinks in water every spring. Villages, settlements and so on… Meanwhile, the drought comes here”.

What is the explanation for all this? In Russia, those involved in policy-making and decision-making processes would probably like ‘to get their slice of that cake’ made from layers of money derived from the natural resources of oil and gas in that region. There seems to be no secret about that. In Moscow, the matter many years ago was being considered, albeit in very general terms and unofficially.

Thus, on Vladimir Pozner’s talk show, Vremena, aired on Channel One June 21, 2008, a question was raised, inter alia, of whether Kazakhstan would agree to pay for Russian water the price that Russia would like to offer. Answering it, Rustem Khamitov, the then head of the Federal Water Resources Agency under control of the Ministry of Environmental resources of Russia, said: Kazakhstan is not going to pay for water, and if it is, only at extremely low prices.

And if so, then here’s what it is. The huge deposits of hydrocarbon resources in the basin of the Caspian Sea which were proven, or discovered back in the Soviet period, have been developed by Western multinationals for decades. Almost all of crude from those fields are being exported to the West. Kazakhstan’s revenues from it feed the national budget and are being used for supporting the subsidy-dependent provinces, of what are composed the country’s all other regions – Central, Eastern, Northern and Southern Kazakhstan.

At the same time, people in the oil-producing region itself are increasingly getting bogged down by social, economic and environmental problems, exacerbated by persistent drought and water scarcity. Not without reason are the richest provinces of the Republic of Kazakhstan, with average per capita GDP, comparable to that of some EU member States, been now called by Russian experts ‘the poverty-stricken West’. It may be assumed that, in its present state, Moscow does not have the luxury of just ignoring such a situation and letting events take their natural course. Anywhere in the post-Soviet space outside of Russia, wherever is appeared a quite strong and serious protesting group, it receives some sort of support from Russia in confronting the authorities in its republic. Not a single CIS country among immediate neighbors of Russia, except for Belarus, has escaped meeting such a fate. It has befallen even Moldova which does not have common borders with the Russian Federation. In this case, the only saving grace for Belarus is probably the fact it signed the Treaty with Russia on the creation of a Union State a long time ago – on 8 December 1999, to be specific.

Speaking of Nur-Sultan, one surely can argue on the grounds that it, unlike Kyiv, Tbilisi and Baku, is a political ally and an economic partner to Moscow in the CSTO and the EEU. That’s actually so. However, as Bruce Pannier, a journalist covering Central Asia, has indicated, yes, really ‘Kazakhstan is one of Russia’s partner-states, but no Russian official is being rebuked for making comments about taking Kazakh territory’. That means the system of government and public opinion in Russia have long been accustomed to the idea that sooner or later Moscow may decide to revise the border between the Russian Federation and its Central Asian neighbor, just as it happened and is happening in the case of Ukraine. Kazakhstan should hardly count so much on its status as a partner and ally of the Russian Federation in the EEU and the CSTO, considering it as some sort of insurance from repeating the Ukrainian experience. Moscow can always find some cause to change favor to anger with regard to any country in the post-Soviet space.

This is particularly true in respect of Kazakhstan. There is no need to go far to make sure of it. It is enough to pay attention to the very recent verbal attacks by Russian politicians and public figures on Kazakhstan, on its government and political leadership. Here is the most recent example of this. Rostov.Tsargrad.tv, in an article entitled “One should speak simply, when talking to Kazakhstan: ‘You should take a bow, be thankful and not object”, said: “Denazification measures and a special military operation should have been applied first of all to Kazakhstan, and not to Ukraine”.

This kind of behavior from Russian political analysts, journalists and politicians causes the observers to believe that those people, when they are itching to assert themselves by humiliating Nur-Sultan, do not bother with waiting some cause for this to appear on the Kazakh side. Because recent experience indicates that they themselves can easily invent pretexts for such attacks. Shortly after the war in Ukraine started, Russian Foreign Ministry spokeswoman Maria Zakharova said that relations between Russia and the West were approaching the point of no return. More than four months have gone by since then. The situation has been altered just for the worse.

At this time one thing is certain: regardless of when and how the war in Ukraine ends, Washington and Moscow (as well as the West and the Russian Federation) are entering upon a lengthy period of – to put it mildly – poor relations. But it is, as they say, a matter for the future. And Russia is already facing serious difficulties in the context of the war that it is waging against Ukraine. The Russian economy has stepped into a recession phase, the main reasons for which are the West’s ‘unprecedented sanctions’ on Moscow in retaliation for the Russian invasion of the territory of a neighboring State.

A European partial embargo on Russian oil coupled with an EU ban on insuring ships transporting the nation’s crude further complicates the situation for the Kremlin. In such circumstances, Kazakhstan might be seen by Moscow as the only party through which it could hope to break this deadlock. The Central Asian country’s western part is just the area in which huge amounts of western investment are concentrated. The Americans and Western Europeans go on acting like they don’t have much reason to be concerned about the fate of those assets while they are trying to ‘force the Russian economy to its knees’ by their sanctions. But it’s unlikely those of them, who are following attentively the latest developments in relations between Moscow and Nur-Sultan, have lost sight of the fact that shortly before the start of the war in Ukraine, some Russian media started playing the card of the need of ‘protecting… the Kazakhs from the Middle zhuz, who are historically and mentally close to us [Russians]’, in contrast to ‘the southern Kazakhs’, and, most importantly, of the ‘deprivation’ of the potentially very rich, but actually ‘poverty-stricken West’ (the Junior zhuz) in the face of the Senior (Southern) zhuz elites’ domination in the country as a whole.

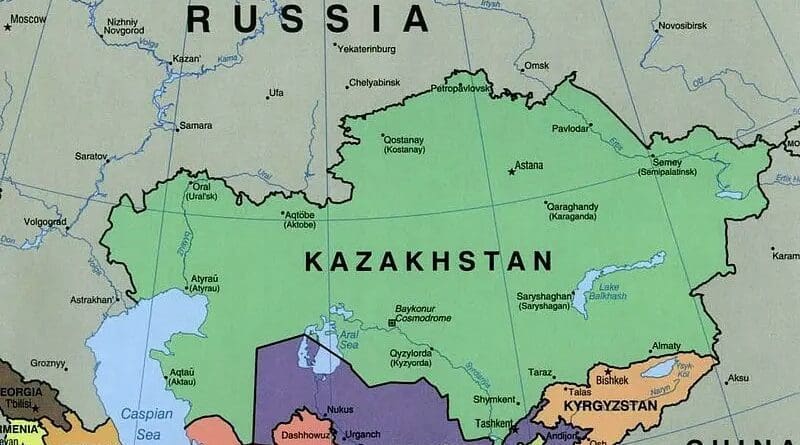

The West most certainly is following the conversations about the likelihood of the collapse of Kazakhstan and the possibility of the emergence of several states on its territory, that have been going on since last year on Russian TV channels and websites. All of this is far from being harmless, the more so in the current situation in Kazakhstan, on the eve of fairly possible social and economic difficulties. Anyway, it appears that Russian media have already begun the process of fomenting divisiveness on the basis of belonging to one or other zhuz (tribal group) in the Kazakh society. In doing so, those Russian political analysts, journalists and politicians present the matter as if it emerged and is becoming a spiraling problem without outside ‘help’.

This seems to be an old political technique which is very similar to what was used earlier in Ukraine. The only difference is that the dividing lines are being drawn not between representatives of the pro-Western and pro-Russian camps, but among the zhuzes in Kazakhstan. And Moscow seems to be willing to reserve the right to support – just as was the case with Ukraine – the side that it would consider wronged by those in power.

In his recent article, this author described the situation with behind the scenes politics in Kazakhstan in the following terms: “Our guess is that obvious signs of the consistently favorable attitude by both Moscow and the Western capitals towards the Kazakh regime are exactly what contribute significantly to the stability of its rule for many years. And Kazakhstan has been and is being ruled by the elites of the Senior (Southern) zhuz. An implied right of that regime to rule the country for a prolonged period or indefinitely is secured, among other things, thanks to the informal consent initially received from Moscow and the West… to support its status as such in exchange for obligations to ensure the protection of their often mutually conflicting interests in the Kazakh context.

Official Nur-Sultan, on the one hand, has guaranteed and will continue to guarantee the invariability of conditions for the implementation of capital investments and the conduct of business in the performance of the contracts concluded with Western transnational corporations at the dawn of Kazakhstan’s independence. On the other hand, the current Kazakh leadership remains committed to supporting all of Moscow’s integration initiatives in the post-Soviet space. It therefore appears that Kazakhstan continues to be both a pro-Moscow and a pro-Western country even in a situation where the confrontation between the Russian Federation and the West reaches its climax”.

But now it looks like times have changed. The current results of this two-vector policy by Nur-Sultan have obviously stopped being passable for the Kremlin. And it has been sending – through Russian media – unequivocal signals to the Kazakh capital about the Russian side’s willingness not only to withdraw its consent to support the Senior (Southern) zhuz status as the uncontested ruling power in the Central Asian country, but also to stir up inter-Zhuz confrontation in Kazakhstan and thus push the country into becoming divided into several states. Here is the latest of such kind of messages.

In his article entitled ‘Kazakhstan may lose its sovereignty: the West has intervened in relations between Moscow and Nur-Sultan’ and published in the Nezavissimaya Gazeta newspaper, Alexander Kobrinsky, director of the Russian Centre for Ethno-National Strategies, said: “The next step is Kazakhstan’s withdrawal from a number of the most important treaties, agreements and organizations in the post-Soviet space. However, Kazakhstan’s estrangement from Russia will inevitably entail the danger of the country’s losing its sovereignty, and probably the matter will not be limited to this. Kazakhstan [the Kazakh people] is a union [made up] of many tribes. And not all Kazakh tribes are of Turkic origin. Among them, there are also those who are of Mongolian origin. The Turkic-speakers should not be confused with the ethnic Turkic peoples. There is a serious danger of the collapse of the State, which should not be underestimated. Multi-vector policy always ends with a coup d’état, which may grow into the collapse of the State”.

Well, like they say, one could not be any more clear. The question remains, however: is Russia really determined to stir up inter-Zhuz confrontation in Kazakhstan and push it into becoming divided into several states?!