The South Caucasus Concert: Each Playing Its Own Tune – Analysis

By FRIDE

By Jos Boonstra*

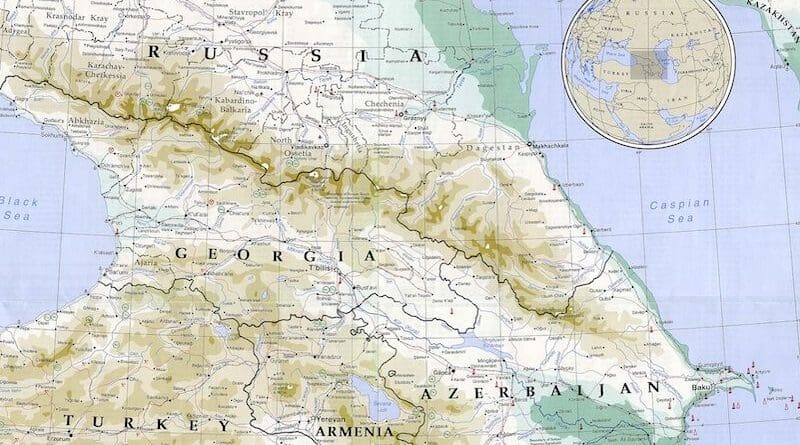

The South Caucasus comprises the former Soviet states of Armenia, Azerbaijan and Georgia. It lies at the crossroads of Europe, the Middle East and Asia and is subject to the often conflicting geopolitical influences of Russia, the European Union (EU), Turkey, and the United States (US). Iran might have an influential role in the region in the future. Armenia, Azerbaijan and Georgia are far from being helpless pawns in this geopolitical contest for influence and affiliation. Indeed to some degree they play these external actors off against each other.

Armenia looks north to Russia for support; Azerbaijan is wary of integration initiatives but close to Turkey; and Georgia’s objectives are fixed westwards towards the EU and US. Together these three countries and the five ‘external’ actors constitute a dense web of interdependent relationships that affects governance and values; security and conflict; and trade and energy.

Russia, however, is by the far the most dominant power as recent and on-going conflicts illustrate: Russia-Georgia war of August 2008 and the current war in Ukraine show very clearly that Russia is prepared to use force to safeguard its interests in neighbouring regions. It will not tolerate closer EU and NATO relationships with former Soviet republics in the South Caucasus. Meanwhile the political will to devote attention and resources to the South Caucasus is more modest in Ankara, Brussels and Washington, not least because of other pressing matters such as the conflicts in Ukraine and Syria. Clearly not every region can be a top priority for the EU, US or Turkey. This paper argues, however, that more awareness and possibly cooperation are needed on the part of Ankara, Brussels and Washington to counter Russian influence and ensure stability. The South Caucasus is a highly combustible powder keg – especially the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict – with the potential to have impacts well beyond its small mountainous area.

This paper sets out a few proposals as to how the EU can increase its engagement with the South Caucasus. It builds on a previous FRIDE working paper – Challenging the South Caucasus security deficit (April 2011)1 – that argued that the EU needed to focus on the South Caucasus to fill the security vacuum left by the partial withdrawal of regional and international organisations such as the Organisation for Security Cooperation in Europe (OSCE). It also proposed that the EU develop a road map outlining objectives for the region, particularly in the field of security. This suggestion remains valid today as the EU reviews its European Neighbourhood Policy (ENP) and drafts a new Global Strategy for Foreign and Security policy.

Although this paper looks at these issues from a European perspective, it also draws on recent papers from two US think-tanks. The first by the Central Asia-Caucasus Institute – A Western Strategy for the South Caucasus (February 2015)2 – stresses the need for increased US-EU cooperation and attention to the region, while outlining a series of proposals to inject new life into western strategic involvement. The second by the Brookings Institution – Retracing the Caucasian Circle (July 2015)3 – makes the case for increased US, EU and Turkey cooperation in the South Caucasus.

The first part of this paper addresses the main interdependencies among external actors and the South Caucasus in a rapidly evolving regional setting. It does so in the light of developments over the last year, especially tenser EU/US-Russia relations and the war in Ukraine. The second part discusses the interests of the EU, Russia, Turkey, the US and Iran (with its potential return after more than a century) in the South Caucasus. The third and final section outlines basic steps that the EU can take to influence democracy and security in the South Caucasus.

A web of interdependent relations

The security, governance and economic development of the South Caucasus are adversely affected by the complex fractious relationships between the individual countries themselves and the geopolitical rivalries and conflicting approaches of powerful external actors that seek to influence the region. This complex situation influences affiliations and integration initiatives, as well as trade, energy, and security. Tensions between the EU/US and Russia over Ukraine are further entrenching these interdependent relations and hampering development in the South Caucasus. Russia essentially considers Eastern Europe, including the South Caucasus, as its backyard where it can act militarily if it feels cornered. For its part, Turkey treads a fine diplomatic line in its dealings with the region so as to maintain good trade relations with both the South Caucasian countries and Russia while remaining on good terms with the EU and the US. This explains its moderate response to Russia’s annexation of Crimea. The EU and the US are all too aware of increasing Russian influence in the South Caucasus but are unsure as to how to counter it. They fear that a tougher stance over Russia’s involvement could lead to conflict, and with so many demands from other regions of the world, they do not regard the South Caucasus as a top priority.

Democracy and affiliation

The Maidan revolution and subsequent war in Ukraine sharpened the divide between the EU’s Eastern Partnership (EaP) programme and Russia’s Eurasian Economic Union (EEU) project. The South Caucasus states have felt obliged to choose to develop an Association Agreement (AA) with Brussels (without the prospect of membership) or to integrate with Russia. Armenia has joined the EEU and Georgia is implementing an AA. Meanwhile Azerbaijan has been able to avoid picking sides thanks to its abundant oil and gas reserves which make it much less dependent on external powers. The choice between the EU and Russia has become more important as regional organisations – the OSCE and the Council of Europe (CoE) – have largely lost their authority and influence in the South Caucasus, while the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation’s (NATO) role remains modest despite Georgia’s membership ambitions.

The choice of affiliation with the EU or Russia also involves choosing a specific economic and political development path. Deeper ties with the EU imply democratic reforms, while integration with Russia’s EEU project means strengthening existing regimes that rely on Moscow for economic benefits and security guarantees. Essentially the EU (plus the US) and Russia seek the exact opposite in their relations with these countries. However, both seem to be better in blocking the other’s plans (an enlarging EEU or a successful EaP) than achieving their own goals (a Moscow-loyal Armenia that is averse to EU cooperation or a fully democratic and secure Georgia resulting from EU association).5 Although efforts to promote Western- style democracy have not had many concrete results, the attraction of the EU remains powerful to the peoples of the South Caucasus and thus carries the potential for democratic reform promoted by the grassroots. But Russia’s direct influence through both coercion (security guarantees and discount energy) and threats (military action and trade embargos) is also omnipresent in the region. The current stand-off over values and affiliation between the EU and US on the one hand (Turkey does not actively promote democracy although is an EU candidate itself ) and Russia on the other will make it difficult for either project to succeed.

Security and conflict

The different allies of the South Caucasus countries do not guarantee their national security. Armenia is a member of the Russian-dominated Collective Security Treaty Organisation (CSTO), but it cannot be sure that Russia would intervene in a renewed war over Nagorno- Karabakh. Azerbaijan is closely allied with Turkey, but cannot count on Ankara should it go to war with Armenia.

Georgia has sought NATO membership for some time but beyond the 2008 NATO Bucharest Summit’s vow that one day it will join, it has not moved much closer to full membership. This geopolitical landscape makes the region unstable and open to a range of security threats including organised crime and Islamic State (IS) recruitment.

Georgia’s potential NATO membership is one of the most incendiary issues. Russia regards it as a direct threat to its own political, military and energy interests in the region (and towards Russia itself ). On 27 August NATO Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg argued in Tbilisi that Georgia is already on track to move towards membership, although he could not say if a Membership Action Plan (MAP) will be on the cards at the July 2016 NATO Summit in Warsaw.6 NATO did not come to Georgia’s defence in 2008 when Russia invaded, and would be unlikely to do so today. Western policies have offered democratisation prescriptions backed up with funding but have neglected to attend to national security concerns of South Caucasus countries; giving Russia in turn a free hand.7

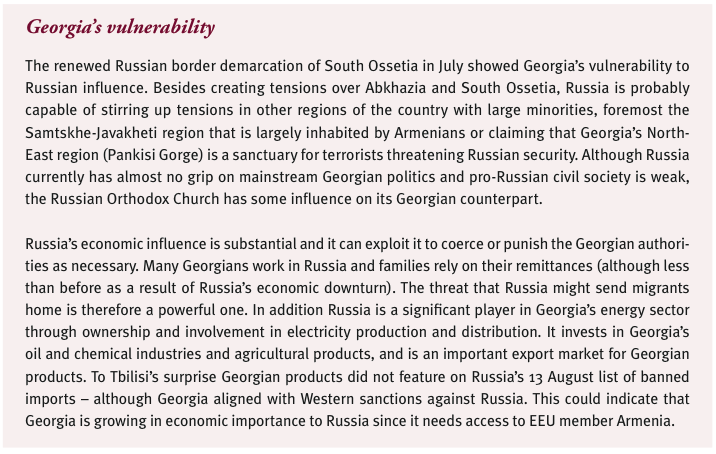

Russia also plays an essential role in the protracted conflicts of the region. The conflicts over Abkhazia and South Ossetia will not be resolved as long as they remain centrepieces of Russia’s influence in the South Caucasus and Georgia more specifically. These two areas’ integration with Russia seem to only differ on paper and in name with Russia’s annexation of Crimea: In November 2014 Russia signed a ‘Treaty of Alliance and Strategic Partnership’ with Abkhazia, and in March 2015 (on the one year anniversary of the Crimea annexation) Moscow sealed the ‘Treaty on Alliance and Integration’ with South Ossetia, in effect incorporating the strip of Georgian territory into Russia.

The Geneva talks – the format that brings together Russia and Georgia as well as representatives from Abkhazia and South Ossetia and chairs from the EU, OSCE and the United Nations (UN) – have not had substantial results after 32 rounds of talks. In the last session of 1 June 2015, Russia complained that Georgia’s integration into NATO would be a security threat to the South Caucasus, objecting to the planned NATO-Georgia Joint Training and Evaluation Centre and NATO exercises in Georgia.8 While these talks were previously described as frank, open and even constructive, Russia increased its involvement in drawing borders. A week later on 10 July Russia continued its earlier demarcation of the ‘state-border’ between South Ossetia and Georgia one and a half kilometres on Georgia-proper territory, swallowing up farmland and houses of Georgian residents, coming dangerously close to Georgia’s East-West Highway, and taking control of one kilometre of the BP-operated Baku-Supsa oil pipeline. Other external actors had no response besides expressing disapproval and concern. Georgia is the main partner of the EU and the US in the Caucasus; a situation that is constantly threatened by Russia.9

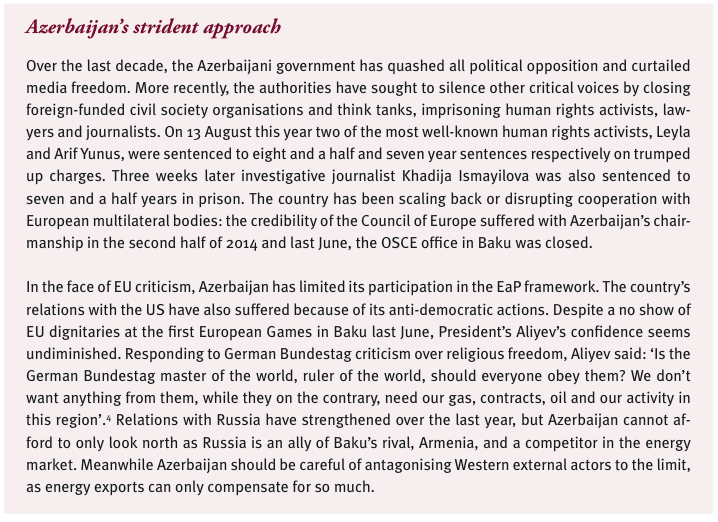

Last year’s events in Ukraine have affected national security thinking in Armenia and Azerbaijan. Armenia wonders what would have happened if they had signed an AA with the EU and passed on Russia’s EEU offer – restricted energy flows; or worse, withdrawal of support to Armenia’s defence? Azerbaijan meanwhile interpreted the Maidan protests as a sign of what Western governments could possibly be preparing in Baku: As a reaction, foreign-funded NGOs and think tanks were evicted or shut down while persecution of critics intensified. On a very different note, the Azerbaijani government is also disappointed with the EU/US stance of supporting Ukrainian territorial integrity, but not offering similar support for Azerbaijan’s territorial integrity concerning Nagorno-Karabakh.

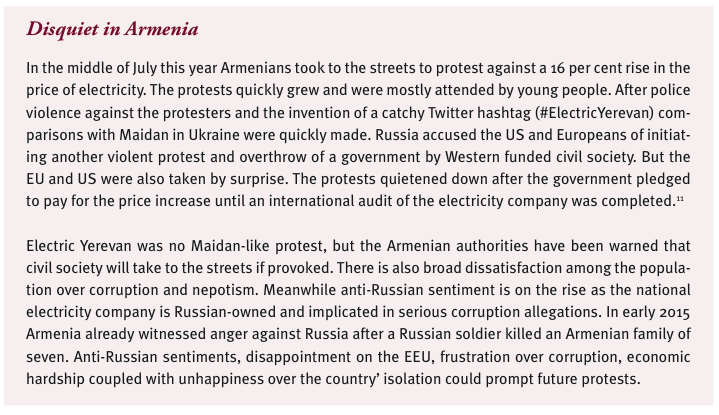

The largest security threat in the South Caucasus is the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan, with regular incidents on the line of contact and a constant threat of these incidents spiralling into mass conflict between the two sides. The current economic downturn in Armenia (due to its closeness to the Russian economy) and Azerbaijan (due to low oil prices) could further destabilise the conflict as both governments might want to distract the population’s attention from their economic problems.

Over the last few years the 18-year old OSCE Minsk format – which brings together the war- ring parties and co-chairs from the US, France and Russia – has proven to be ineffective at conflict resolution though remains the only format to manage the conflict. The 2007 ‘Madrid principles’ by the OSCE Minsk Group were one of the last attempts at resolution. The failure to have Armenia and Azerbaijan endorse the principles was quickly followed by a Russian initiative led by then President Medvedev until 2011 which also ended without a result.

The EU and the US had accepted a Russian lead hoping that Moscow could persuade both sides into an agreement. However, it is now evident that resolving the conflict is actually not in Russia’s interest since it would reduce Armenia’s dependence on Russia while offering new opportunities for Azerbaijan. A resolution to the conflict currently seems further way than ever.

Energy and trade

The South Caucasus countries depend on each other and on external actors in the energy and trade fields, which makes them vulnerable in some respects. Armenia does not have trade dealings with Azerbaijan and Turkey, and largely depends on Russian energy supplies and to a large extent on transit through Georgia. This means that Armenian trade will be very dependent on the EUU, although an expansion of trade with Iran would be welcomed and the EU is now its number one trade partner.10 Azerbaijan will become increasingly dependent on new markets for gas and current markets for oil, since the government has neglected to diversify its economy. Deliveries to Turkey – again through Georgia – are essential: From 2019 onwards Azerbaijani gas going west could reach EU countries in modest quantities when the TANAP pipeline through Turkey to South East Europe becomes operational. So far Azerbaijan has been wary of potential competition from other gas-producing Caspian littoral states – Turkmenistan or Iran. Meanwhile Georgia is dependent on transit revenues and delivery of Azerbaijani gas for its own consumption although it has a substantial hydroelectric sector.

In the energy sphere external actors are fairly (inter)dependent on their small South Caucasus neighbours (both as a source of energy and as important transit routes). For the EU, gas imports from Azerbaijan and beyond would constitute a welcome addition to the mix of imports, but would not substantially lessen dependence on Russian gas (plus others, foremost Norway), especially for Central and Eastern European countries. Turkey relies on Russian gas deliveries (mostly via the Blue Steam pipeline through the Black Sea) for over half its needs, but also has other sources (Azerbaijani gas for instance); a Southern Corridor as foreseen by the EU would be the basis of Turkey’s envisioned geopolitical role as an energy transit hub. In that sense Russian President Putin’s proposal of building Turkish Stream (instead of a South Stream that bypassed Turkey) is welcomed, though not at the expense of Southern Corridor plans with the EU and Azerbaijan. For Russia the main dependency is on the South Caucasus not becoming a viable and substantial alternative for the EU to Russian gas. The US plays no direct role in this configuration in the South Caucasus beyond the business interests of large energy companies, while Iran for the foreseeable future is unlikely to be able to complicate the current configuration of Russian obstruction, Turkish opportunism and EU hesitation.

The hostile relations between Russia and the West have a negative effect on the development of the South Caucasus. They have increased Armenia’s dependence on Russia, emphasised Georgia’s strategic importance at the expense of its development and strengthened Azerbaijan’s believe that it can exploit its energy resource strength to play Russia and the EU/US off against each other. These hostile relations have also severely limited any opportunity for Georgia-Russia rapprochement over Abkhazia and South Ossetia while paralyzing efforts to resolve the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict.

Of vicars, soldiers, merchants and diplomats

As a result of the Ukraine crisis and Russian aggression, external actors in the South Caucasus have fortified their already entrenched positions, interests and preferences. All five major external actors have their own interests: What are these and how can they be categorised?

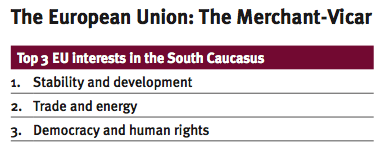

Through the 2009 EaP (which is part of the broader 2004 European Neighbourhood Policy) the EU has become a major investor and actor in the South Caucasian countries. It is the largest donor to the region (under the European Neighbourhood Instrument well over €1 billion has been committed for the period 2014-17 for the three recipient states excluding regional funding, global EU instruments and individual member state assistance).12 The EU is also the largest trade partner of all three countries: Armenia (27.9 per cent of total trade), Azerbaijan (44 per cent) and Georgia (26.7 per cent).13 The aim is to use development aid, democratic reform and a broad (and often fragmented) policy of engagement to promote stability and development in the region and forge closer ties. Nonetheless Brussels’ clout in the South Caucasus remains modest.

Through the 2009 EaP (which is part of the broader 2004 European Neighbourhood Policy) the EU has become a major investor and actor in the South Caucasian countries. It is the largest donor to the region (under the European Neighbourhood Instrument well over €1 billion has been committed for the period 2014-17 for the three recipient states excluding regional funding, global EU instruments and individual member state assistance).12 The EU is also the largest trade partner of all three countries: Armenia (27.9 per cent of total trade), Azerbaijan (44 per cent) and Georgia (26.7 per cent).13 The aim is to use development aid, democratic reform and a broad (and often fragmented) policy of engagement to promote stability and development in the region and forge closer ties. Nonetheless Brussels’ clout in the South Caucasus remains modest.

The difference between Europe’s expressed interests and what it actually can achieve remains substantial, mostly due to the lack of a hard security component and limited political interest. This is shown by the EU’s lack of involvement and influence in helping to resolve the region’s protracted conflicts or presenting a reliable counterweight to Russia’s hard security influence. Hence the EU can be characterised as a merchant due to its leading role in trade and a vicar in its push for democratic and human rights values.

The gap between rhetoric and action also has its bearing on energy and values. Efforts to secure reliable gas imports from Azerbaijan (and beyond from Central Asia and the Middle East) to reduce EU dependence on Russian gas imports, are often highlighted as a priority but little has been achieved over the last decade.

Three significant problems have blocked the EU’s objective of building a Southern Corridor. First, imports from Turkmenistan and Iran via the Caspian Sea and South Caucasus will be very expensive because of pipeline production costs, and will need to overcome many hurdles regarding Caspian demarcation and relations between Azerbaijan and third states. Second, most of the countries that could provide gas to such a corridor are fairly unstable dictatorships (Turkmenistan) or non-proven potentially expensive new options (Iran). Third, Azerbaijan alone will not provide much more gas to the EU, even after completion of the TANAP pipeline in 2019.

Democracy and human rights constitute a third priority and are a major part of EU foreign policy. The track-record of EU democracy promotion has been weak so far with the exception of Georgia. Armenia has not shown much progress in its democracy ratings over the last decade while Azerbaijan has substantially regressed. Where human rights are concerned the EU has a mixed record as well. In the case of Azerbaijan, criticism and concern has been expressed (with the European Parliament leading the way), but at the same time Brussels has sought to persuade the unwilling and annoyed Azerbaijanis back into the fold of EaP mechanisms; this while Belarus, that has a roughly similar poor human rights record, is still on the EU’s sanctions list. This double standard on the part of the EU spurs resentment among its neighbours.

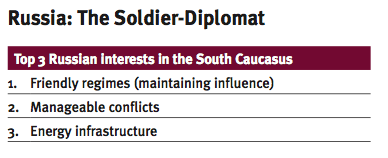

Russia is the dominant power in the Caucasus and is itself a Caucasus country. One of its main concerns is controlling the borders between the Russian northern Caucasus republics (most of which remain unstable and violent) and the South Caucasus. In the South Caucasus Russia’s main interest is not to lose ground to EU and possibly US interests – Turkey has presented itself as less of a threat since it does not seek to influence South Caucasus countries directly, and is regarded as a partner by Moscow despite its NATO membership. In the wake of Russia’s declining trade position in the region and its feeling of being besieged by NATO and the EU, Moscow seeks to avoid developments rather than encourage new initiatives in the region. This also applies to energy diplomacy where Russia seeks to avoid the establishment of a Southern Corridor that would link Azerbaijan, Turkey and Europe at the expense of Russian exports and control of infrastructure.

Russia is the dominant power in the Caucasus and is itself a Caucasus country. One of its main concerns is controlling the borders between the Russian northern Caucasus republics (most of which remain unstable and violent) and the South Caucasus. In the South Caucasus Russia’s main interest is not to lose ground to EU and possibly US interests – Turkey has presented itself as less of a threat since it does not seek to influence South Caucasus countries directly, and is regarded as a partner by Moscow despite its NATO membership. In the wake of Russia’s declining trade position in the region and its feeling of being besieged by NATO and the EU, Moscow seeks to avoid developments rather than encourage new initiatives in the region. This also applies to energy diplomacy where Russia seeks to avoid the establishment of a Southern Corridor that would link Azerbaijan, Turkey and Europe at the expense of Russian exports and control of infrastructure.

Russia’s primary interest is to help shape regimes in neighbouring countries that are friendly to Moscow’s interests; do business in a similar ‘way’ and want to integrate into joint structures (the EEU and CSTO). To this end Moscow also uses soft power mechanisms, foremost through Russian media active in Armenia, Azerbaijan and to a lesser extent Georgia. It tends also to use coercive instruments such as military action and trade embargos. However, South Caucasus countries prefer to keep integration with Russia at bay while seeking a constructive relationship with their northern neighbour. This has led to a situation in which Georgia sees Moscow as a direct threat but pursues practical ties in trade and at the Geneva talks; Armenia feels forced to accept Russia’s patronage but explores modest alternatives through cooperation with the EU; and Azerbaijan develops relations with Russia as part of its policy to play third parties off each other.

Since Russia cannot rely on healthy relations with its three southern neighbours it tries to apply a divide and rule policy through protracted conflicts. In recent years Moscow has beefed up and modernised its military presence in Armenia, Abkhazia and South Ossetia. In Georgia the conflicts of Abkhazia and South Ossetia are controlled by Russia, in part because these regions border Russian territory and have been largely incorporated into the Federation. Russia also plays a substantial role in the conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh through its role as a peace broker (the diplomat), support to Armenia and weapon deliveries to both (to ensure a military balance). Russia is not keen to help resolve any of these conflicts as it uses the managed instability to its advantage, placing the other countries in a dependent situation. Russia mixes diplomacy with military might in such a way to keep the region in limbo and avert its potential for development and local integration. Russia’s objectives and interests are therefore diametrically opposite to those of the EU, the US and Turkey that all three seek development of the South Caucasus, stability and increased energy and trade links.

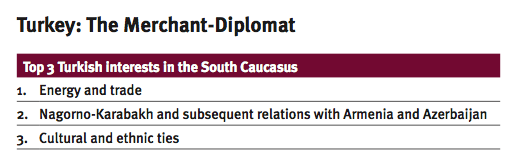

Turkey is an important player in the South Caucasus but has yet to achieve its full potential. The reason for this is that other crises demand more urgent attention (foremost Syria, IS and the Kurds) and Ankara prefers to pursue its energy and trade interests and avoid increased tensions that could aggravate Russia. Turkey is partially dependent on Russian and Azerbaijani gas, but also seeks to become an important transit hub for both producers and European customers which implies a balancing act. Turkey thus seeks to court Russia, the EU and Caucasus countries when necessary but is also able to partially curb them if Ankara’s security interests are tested to the limit.14 While Ankara will need to develop a South Caucasus policy that carefully balances different interests, it is also a NATO member and has deep historical ties with all three South Caucasus states. Turkey has thus the capacity to go beyond a merchant-diplomat role and also promote values (through its civil society) or provide hard security (the soldier). Prospects for Turkish involvement however remain dim as the ruling Justice and Development Party’s (AKP) primary priorities are of a domestic nature – including President Tayyip Erdogan’s claim to power and political survival – while its main foreign policy concerns are also linked to internal matters: the refugee crisis, the Kurds, and Syria.

Turkey is an important player in the South Caucasus but has yet to achieve its full potential. The reason for this is that other crises demand more urgent attention (foremost Syria, IS and the Kurds) and Ankara prefers to pursue its energy and trade interests and avoid increased tensions that could aggravate Russia. Turkey is partially dependent on Russian and Azerbaijani gas, but also seeks to become an important transit hub for both producers and European customers which implies a balancing act. Turkey thus seeks to court Russia, the EU and Caucasus countries when necessary but is also able to partially curb them if Ankara’s security interests are tested to the limit.14 While Ankara will need to develop a South Caucasus policy that carefully balances different interests, it is also a NATO member and has deep historical ties with all three South Caucasus states. Turkey has thus the capacity to go beyond a merchant-diplomat role and also promote values (through its civil society) or provide hard security (the soldier). Prospects for Turkish involvement however remain dim as the ruling Justice and Development Party’s (AKP) primary priorities are of a domestic nature – including President Tayyip Erdogan’s claim to power and political survival – while its main foreign policy concerns are also linked to internal matters: the refugee crisis, the Kurds, and Syria.

Turkey would like to normalize relations with Armenia, and was engaged in an initiative in 2007-10 to this end. However, this initiative was not received well in Baku, which demands that Ankara maintain the link between opening its borders with Armenia and progress in the resolution of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict.

In the South Caucasus, the Turkish ‘zero-problems’ foreign policy did not fare well in the face of various interdependencies with Azerbaijan and Russia in 2010. Since then Turkish efforts to seek progress on the border with Armenia or play a role in resolving the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict have been mostly low-profile and behind the scenes. International commemorations this year of the 1915 Armenian genocide did not help on both matters.

A third Turkish interest – or maybe better, set of assets – are kinship, business and civil society relations. Ankara might not be in the business of democracy promotion like the EU and the US, but it plays an important soft power role throughout the South Caucasus through historic, cultural and language ties. It is these relations that make Turkey – also geographically as a partially Caucasus state – a direct stakeholder. Turkey’s broad informal influence and contacts can be used for a variety of purposes, from promoting development and education to playing a subtle role in conflict resolution.

For the time being Ankara continues its balancing game between Russia and the EU/US, which greatly helps to restrain Russia from acting in the South Caucasus against Turkey’s direct interests. Among these actors Turkey has become a linchpin country as both Russia and the West seek Turkey’s cooperation; Russia in energy and trade preferring Turkey to not get too involved in the region, and the EU and US in seeking Turkish activism (as an EU candidate country and NATO member) in the South Caucasus.

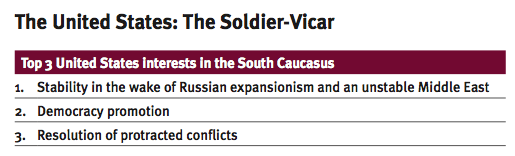

Among the main external actors in the South Caucasus the US stands out since it is geographically so far removed from the region. However, the US has been active in the South Caucasus since the fall of the Soviet Union and is the only country with a truly global reach. American priorities in the South Caucasus are difficult to define. Over the last decade, US interest in the region has been rather low and it has tended to rely on its close partners’ more active involvement – the EU and Turkey (as well as confidence in Russia in 2009-12 as part of the then US-Russia ‘reset’). Currently US energy and trade dealings are small and its main interests are stability and democracy promotion. With this stability the US hopes that the region can be a bulwark against Russian revisionism and an unstable Middle East.

Among the main external actors in the South Caucasus the US stands out since it is geographically so far removed from the region. However, the US has been active in the South Caucasus since the fall of the Soviet Union and is the only country with a truly global reach. American priorities in the South Caucasus are difficult to define. Over the last decade, US interest in the region has been rather low and it has tended to rely on its close partners’ more active involvement – the EU and Turkey (as well as confidence in Russia in 2009-12 as part of the then US-Russia ‘reset’). Currently US energy and trade dealings are small and its main interests are stability and democracy promotion. With this stability the US hopes that the region can be a bulwark against Russian revisionism and an unstable Middle East.

From the 1990s to the mid-2000s the US was an active player in South Caucasus energy politics, and took initiative in the Minsk Group on Nagorno-Karabakh. After the December 2003 Rose revolution, Georgia became central to almost all US priorities in the region. The US has been inclined to extend NATO membership to Georgia but its European allies have been hesitant owing to concerns about Russian reactions. Armenia is also relevant to Washington, in part because of the politically vocal Armenian diaspora in the US. Meanwhile Azerbaijan played an important transit role for the US and NATO in Afghanistan, although current relations have been severely damaged (as with the EU) over human rights and the notion in Baku that the US might be developing plans for a democratic revolution in Azerbaijan.

Washington’s democracy promotion agenda in the South Caucasus has long focused on Georgia (as a ‘beacon of democracy’ in President George W. Bush’s narrative) although ample resources have also been allocated to Armenia and Azerbaijan in the past. While the EU sees Azerbaijan as a potential energy provider, the US is more interested in Azerbaijan’s secularism and strategic position in the wake of an unstable Middle East and questions about Iran’s future direction. In that sense the EU is the merchant and the US the soldier, although both preach a values agenda.

The US is keen to see the South Caucasus develop, solve its conflicts and further integrate into Europe – but the time when Washington could initiate these processes is over, and the EU plays a more influential role given its proximity and economic influence. Nowadays the US is likely to support any initiative taken by Ankara or Brussels that could help resolve conflicts, especially to counter Russian revisionism in Georgia, Ukraine and/or elsewhere. The US role remains limited – though indispensable for Western influence in the region –, curtailed by distance and Russia’s anti-Americanism; in that sense the US policy towards the South Caucasus is now part of a broader policy of countering Russia.

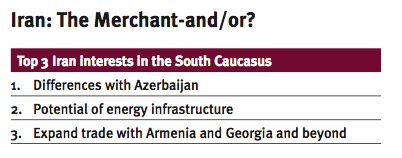

Iran cannot be qualified as a ‘soldier’ as it has no direct or even indirect (via regional organisations) security involvement in the region. Due to its long absence from the Caucasian scene it is no ‘diplomat’, and would find it difficult to find a place at the crowded negotiation tables to help resolve conflicts. A ‘vicar’ also seems unlikely in a region that is predominantly Christian Orthodox, with the exception of Azerbaijan which is Shiite Muslim like Iran, but follows a strict secular policy. A ‘merchant’ it already is, and this role might be enhanced as international sanctions on Iran could be lifted by the end of 2015.

Iran cannot be qualified as a ‘soldier’ as it has no direct or even indirect (via regional organisations) security involvement in the region. Due to its long absence from the Caucasian scene it is no ‘diplomat’, and would find it difficult to find a place at the crowded negotiation tables to help resolve conflicts. A ‘vicar’ also seems unlikely in a region that is predominantly Christian Orthodox, with the exception of Azerbaijan which is Shiite Muslim like Iran, but follows a strict secular policy. A ‘merchant’ it already is, and this role might be enhanced as international sanctions on Iran could be lifted by the end of 2015.

Given that Iran is home to over 15 million ethnic Azerbaijanis, Azerbaijan (population just over 9.5 million) is a major priority for Iran. There is also a religious component to their relationship as both populations are largely Shiite but live under different systems: Azerbaijan’s secular government (with a Soviet heritage) and Iran’s theocracy. There are a few bones of contention between the two. Iran maintains good relations with Azerbaijan’s arch enemy Armenia.

Similarly Baku has dealings with Israel. In addition, a dispute over the delimitation of the Caspian Sea and its resources influence bilateral relations.

Although Iran boasts the second largest gas reserves in the world it has not been able to export; it even imports gas from Turkmenistan. It will take enormous – Chinese or Western – investments to start producing and exporting in either direction. Iranian gas could render the Southern Corridor a more significant source of natural gas for Europe, but this depends on how Tehran positions itself with regards to the West – and how keen Azerbaijan is to block access by Iran or profit from transit as well.

Tehran’s likely third priority is trade with Georgia and foremost Armenia. For the latter Iran has been the only open shared border besides Georgia. Armenia will be keen to expand further on trade and on energy cooperation, while Georgia (though a staunch Western ally) is also keen to extend its business and trade through links with Iran. These prospects could constitute a positive role for Iran in the region without much cost for other external actors.

Iran’s role in the South Caucasus is unclear. It seems unlikely that Tehran will become a substantial factor in the near term as energy infrastructure (if agreed on and built) will take many years to come into being. In addition the region is not a top priority for Tehran given its other pressing priorities such as the rivalry with Saudi Arabia, its policy towards Israel, and broader Middle East challenges, foremost IS. In that sense Iran – like Turkey, the EU and the US – is not interested in becoming too involved in South Caucasus conflicts, leaving Russia to dominate the region from a security point of view. Although Russia would like to have a partner in countering the West, it is unlikely to welcome much Iranian influence in the South Caucasus which it firmly considers its sphere of influence.

Increasing EU engagement

On 20-22 July this year, European Council President Donald Tusk visited Armenia, Azerbaijan and Georgia. Tusk encouraged all three to intensify cooperation with Brussels through the EaP, but also devoted ample attention to the protracted conflicts by speaking out against new border demarcation activities by Russia in South Ossetia, and by urging Armenia and Azerbaijan to curb the violence on the line of contact in Nagorno-Karabakh. While not spectacular news, it constituted an important expression of interest by Brussels.

The South Caucasus needs increased attention from the EU, specifically more high-level visits by officials from the EU and its member states to complement the work of the EU’s Special Representative (EUSR) and the activities of the European External Action Service in the region. Increased contact and visits need to be accompanied by a clearer vision. The following four avenues of potential EU policy thinking could help strengthen the EU’s position in the region to the benefit of the South Caucasus and the EU alike:

Reviewing EU policies

The EU is reviewing several policies this year and next. Most notably Brussels is examining its European Neighbourhood Policy (including its Eastern Partnership component), planning to complete the review in autumn 2015 and is developing a Global Strategy for Foreign and Security Policy to be ready by June 2016 to replace the landmark 2003 European Security Strategy.

In a recent preparatory study for the new Global EU Strategy, High Representative Federica Mogherini assessed the current global environment including the EU’s role with regard to its eastern neighbours: ‘Our approach towards our eastern partners needs to include robust policies to prevent and resolve conflict, bolster statehood along with economic development, and foster energy and transport connectivity’.15 These aspects certainly apply to the South Caucasus and are central parts of a European approach to the region alongside democracy promotion and human rights.

The EU does not need to formulate a specific South Caucasus strategy as it has done for other regions such as Central Asia or the Sahel: this would constitute just another rhetorical document with goals the EU alone cannot achieve. Most essentially the South Caucasus needs to be regarded as part of Europe, and should be approached as such: this would mean stepping up engagement on all fronts, as relations with the South Caucasus directly affect the EU in terms of security (conflicts, energy, and potential refugees). The South Caucasus is not only a matter for foreign policy but also for ‘internal European policy’. This means increasing EU visibility in South Caucasus countries as well as highlighting relations with European neighbours from the South Caucasus in EU member states. If framed well, such an approach should also help to enhance integration without the issue of membership being central to the relationship.

The basis for external action should not lie in creating a new mini-region within the EaP, but building stronger tailor-made bilateral ties with each of the countries: deepening integration with Georgia; building the maximum possible relationship (in the wake of its EEU membership) with Armenia; and being open to cooperation with Azerbaijan that goes beyond energy if the regime becomes more amenable to remedying its human rights shortcomings.

Democracy and human rights

As numerous EU policy documents already state, the development of democracy and respect for human rights should form the basis of EU foreign policy. Among all the reviews and redrafting of EU policies by the ‘new’ EU leadership, the review of the 2012 EU Strategic Framework and Action Plan on Human Rights and Democracy that resulted in a new action plan (2015-19) has not received much attention.16 The EU has found it difficult to ensure member-state support and interest in this core field, possibly because many see democracy support and human rights as rather distinct matters. This also applies to the South Caucasus.

Human rights are of a universal nature and leave little room for interpretation; the South Caucasus states have signed up to numerous international human rights regimes including the CoE and should be held to this. The EU plays an important role in making their policies conditional on the human rights situation in partner countries – this means that the EU should not deviate in its reaction to human rights offences merely because of the countries strategic value for Europe.

Democracy promotion needs to be welcomed by countries to be effective. The EU should uphold democratic values in its external policies to the South Caucasus but deviate its funding and intensity of support along what is possible and welcome. This means that, in countries that are not open to democracy, their civil society needs substantial support (including educational programmes) to engage people, while less or no funding should go to a government that is averse to reform. And countries that have chosen a reform path – where democratisation and state-building go hand in hand – need substantial help that is flexible and conditional on all fronts. Thus, ‘more for more’ and ‘different for less’ in EaP jargon.

The EU needs to understand that its democracy promotion efforts have had little effect so far, but that the Union is still a potential pole of attraction for the average citizen in the South Caucasus. This asset – as well as practical democratisation assistance – should be used to counter Russian propaganda and support for authoritarian rule. However, this also means that demands for reform from the population – sometimes inspired by EU reform rhetoric – need to be answered by the EU with strong support; the EU cannot preach values and then not be prepared for the day when countries are ready to move forward.

Developing a security roadmap

In the absence of an official strategy for the South Caucasus, the EU could develop a simple and clear security roadmap for the region. Such a short document could bring together current EU involvement in security matters – the EUMM border monitoring mission in Georgia, the EUSR’s work, and several EU projects aimed at borders, Internally Displaced People (IDP), and so on – and add a list of new initiatives, for instance on security sector reform (reform of security agencies and strengthening oversight mechanisms). A road map could also devote more attention to the EU’s contribution to the OSCE and outline cooperation with NATO (owing to the EU’s large investment in the OSCE and substantial overlapping membership with NATO). Most importantly the roadmap would present ideas and options on the EU’s role with regard to the protracted conflicts: a clear position on Abkhazia and South Ossetia; and an effort, with others, to initiate talks between Armenia and Azerbaijan over Nagorno-Karabakh. It could also outline increased support to bring Armenia and Azerbaijan’s civil societies together in concrete projects and thereby help build confidence between the two sides.

The roadmap would not constitute a full strategy, but would serve as a list of ongoing items and projects as well as new ideas and plans. Such a vision would also counter criticism that the EU either has no security role in the South Caucasus or that the modest role it plays is too dispersed over Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP), European Commission and EEAS involvement. A roadmap could also assure South Caucasus partners that the EU takes an interest in their security and the link between security and democratisation. Some of the ideas will bear fruit; others will be most likely blocked by the regional and external actors but the position would be clearer and its commitment to security issues more evident.

Cooperation with Turkey and the US

There is a significant overlap of interests between the EU, Turkey and the US. As the South Caucasus is not a top priority for these allies, concrete cooperation and joint action might be difficult but not impossible. The EU should act more strategically in the South Caucasus forging alliances with partners on topics where results can be achieved. Cooperation will need to focus on concrete matters: a discussion of conflict resolution in the case of Nagorno-Karabakh and a united position on Georgia’s protracted conflicts. In addition, they could make joint efforts to develop and protect the Southern Gas Corridor. On the ground the EU and the US will need to coordinate their democracy-related assistance more closely as well as comparing notes on security assistance. The EU could facilitate the involvement of Turkish civil society with their EU and South Caucasus counterparts, for instance through the EaP Civil Society Forum.

Since Russia has by and large diametrically opposing objectives to the EU, Turkey and the US, geopolitical difficulties are unavoidable. Every move that the EU/US make will be met with a response by Russia; the opposite is not necessarily the case as the EU and NATO will not be ready to respond to every Russian action.

Unfortunately there is little scope for cooperation with Russia although diplomatic efforts should continue. The South Caucasus is also a place where both sides meet in diplomatic and civil society circles (as far as independent civil society actually still exists in Russia). Although Iran is unlikely to play a substantial role in the South Caucasus for the time-being, the other actors should not regard Tehran as a threat but instead offer to listen to its ideas, which are likely to focus almost entirely on the economy.

Conclusion

The South Caucasus is a complicated region of interdependent relations over governance and affiliation; security and conflict; and energy and trade. The developments in Ukraine and the rift between the West and Russia have held back the region’s potential development. In the light of weakened influence of regional and international cooperation mechanisms, every powerful actor in the region will need to tread carefully. The risk of Russian intervention in Georgia if it further integrates into Euro-Atlantic structures has risen; the potential for protests and turmoil in all three states is high; and the risk of escalation of the conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh remains very present.

External actors play a crucial role in shaping events in the South Caucasus; often not by meeting their own policy objectives but by blocking the policies of other actors. This most strongly applies to the competition between the EU’s EaP programme and Russian-driven EEU membership. Although Russia has lost its position as number one trade partner to the EU, it is the most powerful actor and prepared to use military force. The EU will want to avoid a new crisis in the South Caucasus and so will the US. Turkey is keen to maintain stability and have reasonable trade-based relations with Moscow. Someday Iran might be a new actor on the scene, but with little capacity beyond its troublesome relations with Azerbaijan and modestly increasing trade. This gives Russia the power to dictate to the region, although it has its own dependencies such as transport links through Georgia to Armenia; the risk of spoiling relations with Turkey; broader resentment among South Caucasus populations and its own economic downturn.

The EU’s position on the South Caucasus as well as that of the EU-US and Turkey (including NATO), is part of their broader relationship with Russia. They have two options: confront Moscow by increasing support for countries that seek closer ties, are willing to reform, and are open to negotiate to end their protracted conflicts; or avoid confrontation and accept Russia’s prerogative to dictate how South Caucasus neighbours will develop. The first option could of course prompt a reaction from Russia that could increase instability in the region but it definitely has more merit long-term. It would need to be backed by political will and resources that link the national security of the South Caucasian nations to democratisation.

The EU will need to seek closer coordination with the US and develop practical ways to include Turkey more directly, also through the EaP structures. Brussels will need to devote ample attention to Russia and the South Caucasus in the current reviews it is undertaking. As part of this exercise it could formulate a security road map of objectives and initiatives. It should further fine-tune its efforts on democratisation and adhere to one standard for human rights, condemning all violations in neighbouring countries. Russia will argue that the EU and the US are conducting the South Caucasian concert while Brussels and Washington firmly believe the opposite is the case. The EU needs to make sure its tune is harmonious for all the peoples of the South Caucasus.

About the author:

*Jos Boonstra is head of the Eastern Europe, Caucasus and Central Asia programme at FRIDE. He is also coordinator of work package 8 on the Caucasus and the wider neighbourhood in the CASCADE project.

*The author thanks Daniel Keohane and Andreas Marazis for their input as well as Leila Alieva, Nigar Göksel and Neil Melvin for reviewing an earlier draft of this paper.

Source:

This article was published by FRIDE as Working Paper 128 (PDF)