Will Cooperative Security Work In South Asia? – Analysis

By Manohar Parrikar Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses (MP-IDSA)

By Arvind Gupta

The concept of national security has been broadened in recent years. Besides traditional military issues and issues pertaining to state sovereignty, the concept now includes many new dimensions. In his 1992 Agenda for Peace, then-United Nations Secretary General Boutros Boutros-Ghali identified “new risks for stability: ecological damage, disruption of family and community life, greater intrusion into the lives and rights of the individual…” The 2004 report of the Kofi Annan-appointed High Panel focused on human rights issues and endorsed the controversial concept of “right to protect” in cases of genocide and gross human rights violations in a country.

Dealing with the wide range of security issues requires a new approach. The conceptual shift that has occurred after the end of the Cold War is that security can be dealt with through cooperation rather than confrontation. The concept of cooperation to deal with security is not new. The Helsinki Declaration of the early 1970s led to détente and the formation of OSCE – an attempt to deal with the security issues of the time through cooperation. But that approach was bound to fail because the underlying idea of détente remained confrontation and cooperation was employed only to minimise the risk of confrontation and not remove it altogether.

Some key features of the cooperative security approach are as follows:

- Globalisation has led to contradictory trends of integration of finances and trade but also fragmentation of communities and societies as a result of which the danger of state failure has heightened. The existential threat of climate change has given rise to many new security worries. No country is in a position to resolve these security problems by itself. It will require the cooperation of others.

- Cooperative security depends upon mutual trust, transparency, attention to global norms and eschewing zero-sum approach to security. It requires a broader look at the concept of national interest.

- Dialogue, transparency, information sharing, capacity building, confidence building measures and asymmetric reciprocity are at the heart of the cooperative security approach.

- Institution building is important for the success of the cooperative security approach. Institutional platforms are required at the national, regional and international levels. At the same time, broad participation of governmental, non-governmental and civil society stakeholders in these institutions is important. Track-2 dialogues serve a useful purpose in this regard.

Several examples of the cooperative security approach can be cited. In South Asia, SAARC is trying to deal with critical issues like climate change, food security, trade, health, terrorism, etc. in a cooperative spirit. Other regional organisations like the East Asia Summit, ASEAN, OAS, AU, SCO, OSCE are also dealing with cooperative security issues. In some cases, conflict resolution is given high priority. In South Asia, due to insufficient trust, conflict resolution has not been discussed at the regional level.

Despite the promise, there are several barriers to success through cooperative security. It takes time to build trust among participants, particularly between those who might be involved in long term conflicts. The capacities required may be insufficient. Perceptions of countries on the nature and scope of threats might differ significantly. Hidden agendas may spoil the show. Thus, there is no guarantee that the cooperative security approach may deliver lasting solutions. However, such an approach may lessen tensions.

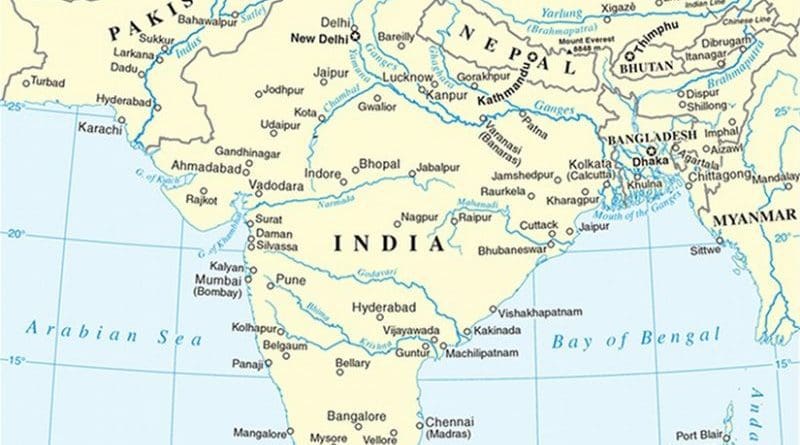

Cooperative Security in South Asia

South Asia has numerous, long standing conflicts left over from history. In the last few years several other issues have been added to the portfolio of security issues. Economic development in South Asia is being threatened by burgeoning human security issues. Many security issues such as demography, economic security, environmental security, terrorism, etc., are issues requiring cooperation among countries of the region. Most states in South Asia are vulnerable to non-traditional security threats. South Asia lacks capabilities and mechanisms to deal with these issues. Is South Asia ready to adopt a cooperative security approach to address some of these issues?

The cooperative security approach to conflict resolution has not succeeded in South Asia. India, thanks to its bitter experience with the UNSC on Kashmir, has categorically ruled out any third-party mediation in Kashmir. Its experience with Russian mediation after the 1965 war (Tashkent Declaration) was none too happy either. The UN’s recent involvement in Nepal and the Norwegian involvement in Sri Lanka’s ethnic conflict were also not successful. India has for long advocated regional resolution of the Afghan problem but Pakistan is opposed to Indian involvement in such a solution. The Afghan problem remains unresolved despite the massive involvement of the international community. Thus, a cooperative security approach to conflict resolution in South Asia has not been successful.

The cooperative security approach might work in South Asia when it comes to resolving human security related issues. South Asian countries are routinely ravaged by floods, famines, hurricanes, pandemics and many other forms of natural and man-made disasters that take a heavy human toll. Floods in Pakistan in 2010, earthquake in India in 2011, Tsunami in India, Sri Lanka and Maldives in 2004, Hurricane Sidr in Bangladesh and Myanmar took thousands of lives. Yet, South Asian countries do not have a mechanism for dealing with natural disasters and human relief. They lack cooperative mechanisms to deal with these problems.

South Asia, despite its high population and common culture is one of the most poorly connected regions in the world. This is because mutual mistrust has prevented countries of the region from giving priority to build multiple connectivities. Intra-regional trade and tourism is at a low level. Building these connectivities will go a long way in mitigating some of the human security challenges in South Asia.

The countries of the region can also cooperate in tacking the challenges of food, water and energy security. South Asia faces the huge challenge of feeding its billions over the next decades. Agriculture, fishing and forestry are the mainstays of food security. South Asian countries are suffering from energy deficits and the picture is becoming increasingly grim by the day. Climate change poses a major threat to South Asia. Yet, there is no mechanism among the countries of the region to come up with coordinated actions.

SAARC provides a forum for discussing these problems and indeed many of these problems have been discussed there. But no credible action plan exists. Although SAARC has been around since 1983, the progress in regional cooperation has been excruciatingly slow. But there are signs of activity. The 17th SAARC summit, held in Addu, Maldives in November 2011, came up with some significant initiatives which might potentially address the human security challenges of the region by strengthening regional cooperation in critical areas.

The SAARC summit declaration emphasised the importance of bridging differences and strengthening the institutions of regional cooperation. The event was notable because concurrently with the summit, the first summit of SAARC Forum was also held. This opens up the opportunity in the future to discuss some sensitive issues which might not be discussed at the formal summits. The summit directed the South Asia Forum to continue to work towards the development of the “Vision Statement” for South Asia on the goal and elements of a South Asian Economic Union.

The summit declaration highlighted a number of issues with significant potential for regional cooperation. These include:

- Reduction in Sensitive Lists as well as early resolution of non-tariff barriers, harmonizing standards and customs procedures.

- Ensuring greater flow of financial capital and intra-regional long-term investment.

- To conclude the Regional Railways Agreement, the Motor Vehicles Agreement, etc. before the next Session of the Council of Ministers.

- To complete the preparatory work on the Indian Ocean Cargo and Passenger Ferry Service.

- To implement the Thimpu Statement on Climate Change.

- To expedite the work on Inter-governmental Framework Agreement for Energy Cooperation, the Regional Power Exchange Concept, SAARC Market for Electricity.

- To resolve the operational issues related to the SAARC Food Bank.

- To initiate work towards combating maritime piracy in the region.

- To direct the finalization of the work on the elaboration of the SAARC Regional Convention on Preventing and Combating Trafficking in Women and Children for Prostitution.

- To undertake a comprehensive review of all matters relating to SAARC’s engagement with Observers, including the question of dialogue partnership.

The above list shows that South Asian leaders are aware of the problems that need resolution through regional cooperation. But, the bane of SAARC has been its inability to convert promises into actions. In the future SAARC members need to show political will and urgency to deal with sustainable problems that confront the region. The setting up of a SAARC Forum and the likelihood of dialogue partners are precisely the innovations that SAARC requires to give boost to the cooperative security approach in the region.

South Asian countries need a bolder approach to cooperative security than has been the case so far. For instance, they can initiate a regular mechanism to discuss security issues in the regions like ARF, CSCAP, etc. Disaster management authorities, finance ministers, health misters, environment ministers can meet regularly to discuss the ways and means to meet the common challenges of disaster mitigation, economic cooperation, public health issues and environmental security. India, which has borders with most SAARC countries, can set up cooperative mechanisms for better regulation of orders. Defence cooperation can also be an excellent way of building confidence and reducing tensions. Maritime security and coastal security should be given higher priority. What is required is political will to implement a cooperative security approach.

The author holds the Lal Bahadur Shastri Chair at the IDSA. The views expressed here are personal.

Originally published by Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses (www.idsa.in) at http://www.idsa.in/?q=idsacomment/WillCooperativeSecurityWorkinSouthAsia_agupta_131111