US: Government Has Planted Spy Phones With Suspects, Says HRW

United States law enforcement has used undercover distributions of phones to monitor suspects’ activities, raising rights concerns, Human Rights Watch said Friday. The Justice Department should disclose its policies regarding the tactic and whether it is currently being used.

Human Rights Watch has identified two forms of this technique that the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) has used or, evidence suggests, has contemplated using. One involved the undercover sale of BlackBerry devices whose individual encryption keys the DEA possessed, enabling the agency to decode messages sent and received by suspects. The second, as described in a previously unreported internal email belonging to the surveillance software company Hacking Team, may have entailed installing monitoring software on a significant number of phones before attempting to put them into suspects’ hands.

“Putting a smartphone whose security has been compromised into circulation could create privacy and security risks for anyone who ultimately uses that device and jeopardize free expression,” said Sarah St.Vincent, researcher on US surveillance and domestic law enforcement at Human Rights Watch. “Who’s going to speak freely on the phone if they have to worry about whether it’s bugged?”

Both techniques for distributing compromised phones raise human rights concerns for a broader range of smartphone users, including peaceful activists whose groups may be at risk of government monitoring and non-suspects who may obtain the compromised phones. They also prompt questions about what rights protections the government is applying if the tactic remains in use.

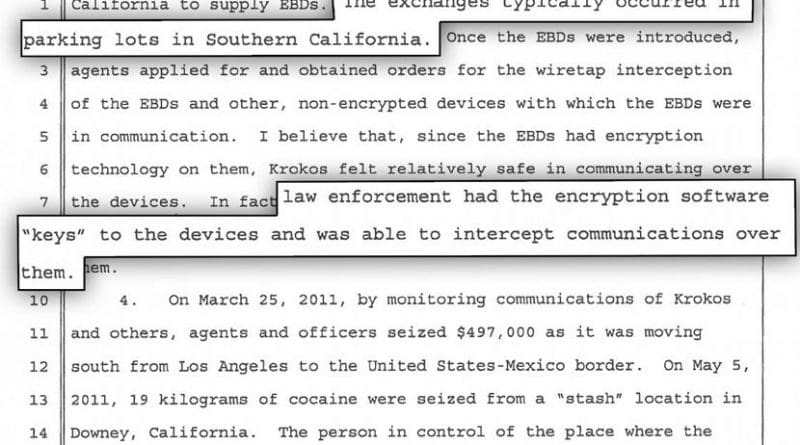

The DEA’s use of the first technique is revealed in court documents filed in 2012 and 2014 during the prosecution in southern California of an alleged drug ring. The traffickers included John Krokos, a Canadian citizen whom the authorities believed was involved in smuggling cocaine between the US, Mexico, and Canada. In early 2010, Krokos and some of his associates began buying encrypted BlackBerry devices from a source in California without realizing she was an undercover DEA agent, as first reported by the Arizona Daily Sun and Vancouver Sun but examined here in detail for the first time. The US also used an undercover law enforcement agent to sell Krokos’ ring some encrypted BlackBerry devices in Mexico in late 2009, although that agent’s institutional affiliation is unclear.

After members of Krokos’ ring were arrested, the government revealed that it had held encryption “keys” allowing it to decode messages agents intercepted from the devices. An affidavit indicates that the intercepted communications included the content of emails.

A court filing suggests that from at least mid-2010, agents obtained wiretap warrants for the real-time monitoring of the compromised devices. However, the available documents do not mention whether a court authorized the dissemination of the devices at the outset. The DEA also attempted to prevent the suspects from buying non-compromised encrypted BlackBerry devices from other sellers, including by arranging for shipments of such devices to be intercepted in Mexico.

The available documents do not suggest that BlackBerry knew about these activities. In response to a request for comment, BlackBerry told Human Rights Watch that it had no involvement in the Krokos investigation. It said customers purchasing BlackBerry devices – in this case, apparently the US government – receive the keys to the encryption used on those individual devices.

The company further stated that it does not possess copies of the encryption keys for the devices it produces and therefore would not have been able to provide them to the government, even in response to a court order. Control over a device’s encryption key is solely in the hands of the customer, the company said.

The DEA declined to comment on these issues due to ongoing proceedings arising from the Krokos investigation.

Ensuring that it holds encryption “keys” to decode communications may not be the only way US law enforcement may make a phone vulnerable before selling or giving it to a suspect. This possibility is illustrated by a previously unreported May 20, 2015 email between personnel at Hacking Team, an Italian firm that has sold surveillance technology to governments. The message, which has no known connection to the Krokos investigation, suggests that the government may seek to infect phones with surveillance software before agents distribute these devices to suspects (or cause others to do the same). A later Justice Department letter to Congress reported by Motherboard acknowledged this technique, but the Hacking Team email raises new questions about the method’s scale and details.

BlackBerry responded to Human Rights Watch’s request for comment regarding the May 2015 Hacking Team email by stating that it had had no involvement with Hacking Team and that its analysis had not revealed any compromise of the security of its platform by the surveillance company.

The US government’s policies for secretly distributing devices it has compromised by obtaining encryption keys or installing surveillance tools largely remain unknown. Documents the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) disclosed in 2011 mention seeking a warrant explicitly for a “two-step” process of installing a spying mechanism on a US computer and then carrying out surveillance, but it is unclear whether the DEA has adopted similar standard procedures for the measures it has used or considered.

Under international human rights law, all surveillance methods that interfere with privacy should be authorized by clear, publicly available laws; be subject to approval by a court or other independent body for specific purposes such as protecting public safety or national security; and be proportionate to those aims. Undermining the security of devices to conduct surveillance could have long-term repercussions for privacy, including for people other than the original intended surveillance targets, making it all the more important for the Justice Department to disclose its policies regarding these tactics.

“These are intrusive investigative methods with potentially far-reaching rights consequences in the US and globally,” St.Vincent said. “The Justice Department should disclose its policies for spreading vulnerable devices around, whether in the US or elsewhere – and Congress and the courts should be vigilant in preventing potential abuses.”