Navigating Asia Away From Chaos: Sri Lanka’s Post-War Ramifications On Region – Analysis

Sri Lanka’s recent military defeat of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) spelled wide and deep ramifications for the whole of South Asia. Ripples of these consequences can now be felt in as distant destinations as China, thus widening the scope of relevance to include Asia in its entirety. The recent Tamil Nadu antipathy towards training Sri Lankan military personnel there spawned a fresh wave of discussion about the regional security dimension of the end of war in Sri Lanka, a hitherto under-analyzed aspect.

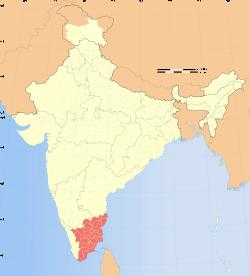

The Tamil Nadu Crisis

Jayalalitha Jeyaram, Chief Minister of Tamil Nadu, has consistently been a strong and outspoken supporter of the LTTE. One of the most celebrated features of her election manifesto in the 2009 parliamentary elections was the pledge to dispatch Indian troops to establish an Eelam in Sri Lanka by force. Her allegiance to the LTTE was recently re-expressed in her opposition to training Sri Lankan military personnel in Tamil Nadu, where she accused the central government of having a “callous and adamant attitude” that demonstrated “utter disrespect to the sentiments of the people of Tamil Nadu.”

LTTE’s defeat still appears to be conditioning the collective mindset of Tamil Nadu, the result of which is the intolerance of even the presence of Sri Lankan military personnel there. Seeking to avoid domestic friction at all costs, Delhi promptly announced that the officers in question will be transferred to Karnataka, on the rather dull excuse that the training session hosted by Chennai was over and the next phase of the said training would be hosted by Karnataka.

Hints of Regional Fractionalization

Colombo has declared its hope to turn towards Pakistan, a strategic prospect stemming from Tamil Nadu’s increasing protests against training Sri Lankan military personnel anywhere in India. Indeed, such an arrangement with Pakistan would not only accommodate the immediate stipulation to host the military training program denied by India, but would also imply a subtle yet unassailable challenge to Indian supremacy in South Asia. Given the cozy relationship between Pakistan and Sri Lanka that has been mainly defined by mutual military assistance rendered at the most crucial of hours – which, in fact, was against India herself at times – this tendency should very well concern the power pockets of Delhi seriously. As Walter Jayawardhana observes Delhi’s dilemma in his news article Buckling under many protests in Tamil Nadu 27 SL Air Force trainees sent to Karnataka written for LankaWeb: “With the discrimination against Sri Lankan Tamils by the majority Sinhalese in the island nation being a hugely emotive issue in Tamil Nadu, the Centre has always had to strike a fine balance between domestic political sensitivities and larger strategic considerations.”

Adding yet more spice to this churning broth of political chaos is the Chinese interest in Sri Lanka as a strategic pawn against India. The context provides a convenient excuse for China to pave a path into the island by way of military support. Jayawardhana elaborates on how this factor shaped Indian conduct during the war against the LTTE. “Even when the Sri Lankan forces were earlier battling the LTTE, India’s strategy to provide non-lethal arms and military training to Colombo, coupled with intelligence sharing and `coordinated’ naval patrolling, was primarily aimed to counter ever-growing strategic inroads into the island nation by both China and Pakistan.”

However, this history does not appear to be potent enough to negate the present circumstances unless India considers curbing the urge to appease a member of the union in exchange for a less challengeable hold over the region. Disintegration of the Indian union is a less plausible risk than that of challenged regional hegemony. Especially given the obvious mutual benefits that Sri Lanka, Pakistan and China would have in a coalition that does not necessarily involve Delhi, India is clearly treading deep waters.

Sri Lanka – Pakistan Military Relations

Sri Lanka – Pakistan relations, as stated previously, have been largely military in nature, sprinkled with a very healthy dose of reciprocal loyalty gradually developed through a string of instances of two-way cooperation. When in 1971 Indira Gandhi banned the entire fleet of Pakistani aircrafts – both civilian and military – from Indian aerospace after a Pakistani intelligence mission of high jacking an Indian flight was revealed, Sri Lanka let Pakistan use her air ports for re-fuelling purposes, a strong sign of allegiance to a struggling nation still young to existence. The tradition of purchasing arms from Pakistan on a large scale by Sri Lanka was initiated in 1999 when President Kumaranatunga assumed power. The timing later proved to be perfect, for in 2000 when Sri Lankan troops were trapped in Jaffna with no means of survival whatsoever, and the LTTE was encroaching to re-capture their former base from every direction, Pakistan supplied weapons that were crucial to the freeing of the Sri Lankan troops.

In 2008, talks between the military heads of the two countries resulted in Sri Lanka purchasing 22 high-tech war tanks from Pakistan, in a context where India was not in a position to render such military cooperation due to internal preassure from Tamil Nadu. During the final stages of the war in Sri Lanka in 2009, Sri Lanka tripled the amount of war weapons purchases from Pakistan. Sri Lankan police and intelligence service officers are also trained by Pakistan. The most recent renewal of these ties will probably be marked by the execution of the prospective plan to train Pakistani military personnel in Sri Lanka as per the request of Pakistan after Sri Lanka’s defeat of the LTTE.

Sino – Sri Lankan Military Relations

China, one of the most potent economic powers in the world, has viewed her relations with Sri Lanka largely in terms of wider strategic interests. Indeed, Sri Lanka being one of the first countries to recognize the People’s Republic of China as a state stands as a watermark reason for this cooperation, but in the context of her current quest for regional supremacy, gratitude is of nearly no consequence to China. The steady flow of defense equipment from China to Sri Lanka during the war is a fact that largely owes to India’s huge presence in the island. In order to counter centuries of cultural exchange and its resultant congeniality, China would need heavily-felt instances of assistance. Apart from supplying arms for overt military action, China has played a crucial role in the international arena to discourage western powers from interfering with the war in Sri Lanka by using the power of veto at the UN Security Council. Hence the domestic sentiment of the island is assuming an increasingly pro-Chinese stance.

Regional Security Implications

If Tamil Nadu succeeds in preassurizing Delhi into terminating all training programs hosted for the benefit of Sri Lankan army personnel, Indo-Lanka relations would become seriously strained. Especially in light of the tension caused by India’s determining vote that ensured Sri Lanka’s defeat at the recent UN Human Rights Council, the two neighbours should conduct their affairs with caution. India was the one regional exception at the Human Rights Council to exhaust her vote against Sri Lanka. All other neighbours either voted in favour or abstained altogether. As such, there seems to be an increasing tendency of India becoming regionally isolated.

Colombo has already confirmed Pakistan as a substitute host for the military training program. Pakistan for whom welcoming these military officers could serve vital strategic interests in terms of securing regional alliances and thereby forming a lose front to face India during a potential clash, would readily conduct the training program that was denied by India.

Naturally, as explained, China would be alert to the benefits stored for her in this kind of development. If, by hosting a few military training programs, she could negotiate mutually beneficial military arrangements with Sri Lanka and Pakistan, China would be geographically blocking India from three sides in a potential war not unlike that of 1962. Of course in the absence of impending war, such an agreement would come in the form of a Chinese-led [ostensibly] political alliance with heavy military connotations excluding Delhi.

The real danger these developments poses is the probability of US intervention in regional affairs to prevent a perceived threat of leftist power proliferation. As has been proved through numerous instances in recent history – the most glaring of which being Afghanistan and Iraq – US intervention, under whatever pretext, is a disaster. It is, then, a regional obligation of all Asian countries to conduct their affairs in such a way that would not leave space for any pro-interventionist interpretation of events by the US.

A point to be noted here is that US involvement in this context would necessarily involve connotations of anti-leftist politics given that China is a declared leftist country while Sri Lanka and Pakistan seem to be showing increasing bias to the leftist ideology. As such, the situation would most certainly stimulate Russia to join the probable power play and its inevitable proxy wars. With their weak economies and wobbly political cultures, neither Sri Lanka nor Pakistan would sustain if used as pawns of a proxy war even with Chinese and Russian help. Even the Indian economy would suffer huge dents the compensation of which would take decades of hard work. Can India really afford a setback of this scale at a point when her economy is decidedly accelerating?

The magnitude of the problem could only be properly appreciated if all countries involved are ready to compromise their inflated egos for the sake of Asia. No one country or single coalition is supreme; cooperation of neighbours is essential for the survival of any country. Hence the Asian community should opt for unity for the sake of survival and autonomy.

Conclusion

In order to avoid a collapse into chaos, Colombo should refrain from aggravating Tamil Nadu. Exhausting other available options without placing India in a compromising position should be able to achieve this end. Even if these options mean Pakistan and China, if the context is such that Colombo does not involve Delhi at all, there would be no issue of turning to these countries because India denied accommodation. This would simultaneously serve two purposes. 1) Tamil Nadu would not have an excuse to complain. 2) Colombo could continue its cordial relations with Delhi without the discomfort of underlying tensions.

Tamil Nadu, on the other hand, should minimize its efforts to preassurize the center to gain their own narrow and self-serving ends. If the general populace of Tamil Nadu was disturbed by the presence of Sri Lankan military personnel, it should have appeased the state government to have them removed from Tamil Nadu only. Since other parts of the country are not under its jurisdiction, Tamil Nadu should take care to identify and operate within its limits.

The center in turn should play a stronger role because there is no actual threat of Tamil Nadu breaking away from the union despite having numerous excuses to do so. The abstention from secession owes not so much to the lack of an incentive as to the lack of self-reliance. The grievances regarding the LTTE alone should have been potent enough to spur a movement to break away. The absence of such an occurrence owes largely to the fact that Tamil Nadu depends on Delhi for financial and military stability.

Delhi, therefore, could safely assume a more firm stance if Tamil Nadu shows signs of operating out of its power orbit.

If the above measures are implemented they would presumably render a relaxation of Indo-Lanka relations, thus discouraging any interest China might have due to the lack of space for manipulation. There would be no question of serving Pakistani strategic interests in such a context because Sri Lanka would not be turning to Pakistan as an option against India. The ultimate result of these steps, if implemented, is regional autonomy. If Asia is to progress, its fate should be in its own hands because neither the US nor Russia would prioritize the best interests of the region over their agendas.

Hasini Lecamwasam is a second year undergraduate of Political Science at the University of Colombo, Sri Lanka. Her other areas of study include International Relations and History. Hasini volunteers for United Nations and Sri Lanka Unites and currently writes on post war reconciliation and changing security paradigms in Sri Lanka.

Good Article and analysis. However the anlaysis is incomplete as the core issue has not been discussed – Sri Lanka’s handling of power share, establishing peace and stability post war in its nation. There are a lot of questions here which is creating an imbalance for Tamils living in Sri Lanka. This in turn creates an opportunity for Tamil Nadu to pressurise New Delhi both morally and politically. India therefore, as discussed in this article, would not be able to support Sri Lankan policies especially if they are against Tamil civilians living there, creating a political and strategic turmoil in South Asia. So it all boils down to what stand – decisive and honest – that Sri Lanka takes in handling the Tamil community and sharing power with them in a democratic process. Normalcy, in a truer sense, should prevail in Sri Lanka which will strengthen Indian ties too.

A proper political mandate inclusive of all communities much like the Indian setup is what is required. After all Sri Lanka is a neighbour of the largest democracy of the world. And they can take a leaf or two from them.